'An Englishwoman's Life in Communist Hungary': Chapter 3, Part 6.

- 10 Jan 2023 1:28 PM

Now You See It, Now You Don’t and House of Cards have been included as part of the Open Society Archive dedicated to this period in the CEU. You can read a serialisation of them here on Xpatloop. You can also buy the dual-volume book on Kindle as well as in Stanfords London.

Chapter three: Market and May Day: Garay tér

Part 6 – Visit to a police station, and the British Ambassador’s

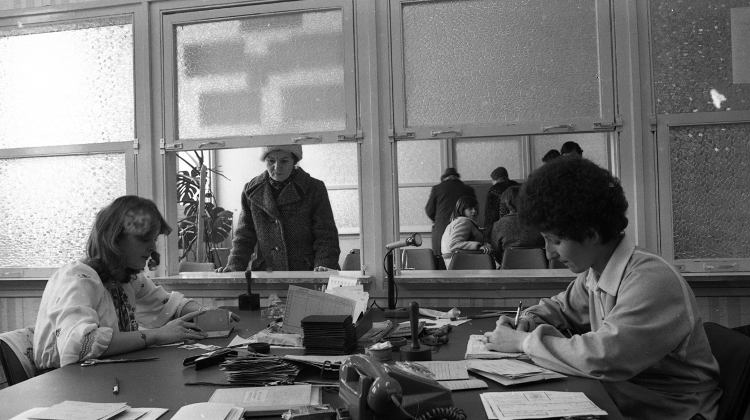

At the main door of the police building stood a policewoman, and it was only after informing her of what you wanted that you were handed a numbered tag, and allowed in. We wandered up to the first floor to find every chair and most available floor space covered with rucksacks and student-types of various nationalities.

The doors along the corridor, which were all shut, had the names of countries above them. After watching and waiting for a short while, it became obvious that no queuing system operated, and due to the large numbers of people it was not even possible to determine who was waiting to go into which room.

Scanning the names of the countries above the doors - all written in Hungarian of course, thus rendering many quite unrecognizable: for example, Olaszország (Italy), Lengyelország (Poland) - we decided that the best ploy was to feign ignorance and go into whichever room seemed least busy.

We tried the handle of the door with several Far-Eastern countries named above it and slowly walked in. The office was unremarkable - a few tables, chairs, lino floor, the smell of coffee, a limp spider plant in the window and a pall of smoke hanging over everything. ‘

Yes?’ said a man in sandals, an open-neck shirt, coffee glass in one hand, and cigarette in the other. We began to explain about the form. ‘Impossible,’ he said, ‘I can't do it. If you only have a temporary permit, you have to pay for tickets in hard currency.’

‘But we don't earn any!’ I protested, and pointing at Paul's contract I continued, ‘Look. This is what we earn. We are not here on a grant or with the embassy. We have work-permits and we work here earning forints.’

‘I'm sorry. Only those with a permanent resident's permit can buy their tickets in forints.’

‘And how can you get one?’ I asked.

‘If you settle in Hungary.’

‘What does that mean? How long do you have to be here for that?’

What it meant was that you had to be married to a Hungarian. Even if we decided to stay for twenty years, we could get no other type of permit than the one we had. The man agreed that it was unfair for us, but pointed out that we were a unique case, and rules were made for the majority.

We left, handing back the tag, and made for the Művész Cukrászda nearby to decide what to do next. It was cool and airy with marble table-tops, green plush period furniture, waitresses in black skirts with small aprons, and an atmosphere of timelessness.

At the table in the corner was a group of maybe eight or nine elderly people, cups of coffee and small glasses of mineral water before them. Some minutes later a newcomer arrived, at which point the men rose, kissed her hand and fetched another chair, while the conversation which revolved around illnesses, doctors and forthcoming holidays, continued.

When the waitress had a minute, she went over to them, chatting in a friendly, familiar manner; it was obvious that this same group met here regularly.

The Művész Cukrászda Courtesy Fortepan/Budapest Főváros Levéltára

At the next table was a man reading a novel, another reading a newspaper and two women bent over a crossword puzzle.

It did not take us very long to decide what we had to do. Miklós liked a problem to solve, and recently had had less to do as our ability to cope with Hungarian improved and we got to know the ropes. In the corner on the wall was a telephone, so taking a couple of two-forint coins, I went to ring him.

Public telephone Courtesy Ami Volt

Fifteen minutes later we got off the tram at Rákóczi tér. There were no girls around, though a couple of men were hanging about outside the flower kiosk on the corner. We groped our way up the dark stairway (we never trusted the lift that lurched and screeched its way up) to the first floor, and went in.

Clearing copies of The Herald Tribune and the Economist off the chairs, Miklós sat us down and brought us coffee. Then settling himself in the armchair with a glass of cognac and lighting a cigarette, he said, ‘OK. Tell me.’

Paul explained while I helped myself to some of the melon from the bowl on the coffee table. When he had finished, Miklós, stubbing out his Marlboro into an already full ashtray, said, ‘There's only one thing I don't understand… Why didn't you come before?’

Then he told us that quite recently he had needed just five dollars to pay someone who had brought a book for him from America, and he was recommended to go and see a woman working as a cosmetician in one of the hotels. She asked him how many dollars he wanted, to which he had replied ‘Five’. Her immediate response was, ‘Five hundred, or five thousand?’

It was reasonably cool in the room, the wooden shutters allowing only a few dusky shafts of sunlight through, giving a warm, subdued light. It was untidy as usual, illustrating the endless comings and goings with no time to finish one thing before starting the next: magazines, newspapers, letters both opened and unopened on the table, teaching books with hastily-scribbled lesson notes on scraps of paper tucked inside, unmarked pieces of homework, cassette tapes, unwashed coffee cups and glasses, clean clothes in piles on chairs, newspaper cuttings, telephone numbers scrawled on serviettes, and ashtrays balanced on bookshelves.

The phone rang, as it did literally every few minutes, and we said goodbye as Miklós pulled out the following week's Lingua timetable from under a heap of newspapers, lit another cigarette and said he would contact us.

By the following evening we had the required amount of money in a variety of currencies: dollars, German marks, Swiss francs, Austrian schillings and a few pounds of our own.

The next morning at the British Airways office the same woman asked me what currency I would like to pay in. ‘Mixed,’ I replied. ‘How mixed?’ she asked. I put the little heaps of notes of different denominations onto the desk.

It must have been obvious how I obtained the money, but quickly calculating the total, she confirmed our reservation and handed me the tickets, no questions asked.

It was towards the end of May that Péter had called in from our previous flat in Dózsa György út, bringing a letter for us that had been sent to the Vántus Károly address. It was from the embassy; despite having registered both the Dózsa György út and the Garay tér addresses, they were still sending things to our first flat, and it was only due to the goodwill of the woman there that she forwarded them to Péter who then brought them to us.

It was an invitation from the Ambassador, printed in black with the royal crest embossed in gold, to a celebration of the Queen's Official Birthday in June. British residents were apparently invited to this event, and never having been to anything similar, we decided to go. It was to be held in the garden of the Ambassador's residence in a very beautiful part of Buda.

Taxi rank Courtesy Fortepan/ FŐFOTO

We travelled by taxi, the weather was unbearably hot, and the thought of squeezing ourselves on to trolleys and trams full of warm, sweaty bodies was decidedly unappealing. Dressed in suitable 'garden-party' attire, we set off.

We crossed the river and started up Rózsadomb, but as we approached the road leading up to the Ambassador's residence we were stopped by police. Ahead of us was a long queue of black shiny limousines, sporting the flags of various of nations, and from behind tinted windows ambassadors and VIPs waited for their chauffeurs to pull up outside the residence.

The taxi driver suggested we walk the last hundred yards, and indeed there was a constant stream of people heading in the same direction on foot. Outside on the pavement stood a long file of men in suits and women in floral creations (one or two even with hats), clutching their invitations and glancing around for a familiar face. We joined the queue and shuffled slowly but steadily towards the door.

It was then that I noticed we were being watched from numerous balconies of flats all around; Hungarians had prepared as carefully for this afternoon as those with invitations.

Sitting in shorts and swimming costumes they had arranged tables and chairs on their verandas, with drinks, snacks (and probably friends invited too), while those without such a vantage point hung gaping from their windows.

This spectacle had obviously become an annual event for local residents as much as Royal Ascot Week or Henley Regatta in England. Few people in the queue seemed to have noticed, or perhaps more likely had chosen to try to ignore this goldfish bowl sensation, and pretend the party was every bit as private as one behind the walls of Buckingham Palace.

After a little time we reached the door and passed into a large hall, where the Ambassador and his wife stood to one side, with one or two other embassy staff opposite. Invitations were not requested; we simply shook hands with the Ambassador and walked straight on out through the French windows and on to the lawn.

I deliberately use the word 'lawn' since it is an item of such rarity in Hungary. It was already covered with guests who included the Primate of Hungary, Hungary's Chief Rabbi, film directors, ambassadors from many other embassies and an assortment of top people from various fields.

Around the borders of the garden were small tables shaded by parasols, from behind which butler-like looking waiters served a large variety of drinks. Meanwhile, waitresses in black skirts and white aprons circulated inconspicuously, carrying silver platters of assorted savoury delights on cocktail sticks; one was only enough to identify the taste and to get any more you had either to be brazen enough to take two or three at a time, or swallow one down and grab another before the waitress disappeared.

Drinks, on the other hand, were available in unlimited quantity, the imbalance in the intake of alcohol and food creating a noticeable effect in some people after an hour or so. Guests stood in small groups, some chatting relaxedly, drink in hand, others indulging in raucous laughter.

Two hours later, having managed to waylay the waitress only once or twice more, we were feeling hungry and tired of standing. We had met several people we knew, but they too had either left or were leaving. Some Hungarians obviously saw the opportunity to make the acquaintance of someone who might later be useful to them and hovered on the edge of a little cluster hoping to catch the eye of someone they already knew and be admitted to the group.

I had expected some kind of formal toast to the Queen, but no such event seemed to be in prospect, so we made our way back through the elegantly decorated hall, stealing a look at the antique furniture in one or two of the rooms whose doors were open, and then strolled back down the road to the nearest bus stop.

Click here for earlier extracts

Main photo: At the Police Station Courtesy Fortepan/ Magyar Rendőr

LATEST NEWS IN community & culture