'An Englishwoman's Life in Communist Hungary': Chapter 3, Part 8.

- 23 Jan 2023 7:52 AM

Now You See It, Now You Don’t and House of Cards have been included as part of the Open Society Archive dedicated to this period in the CEU. You can read a serialisation of them here on Xpatloop. You can also buy the dual-volume book on Kindle as well as in Stanfords London.

Chapter three: Market and May Day: Garay tér

Part 8 – Poles in Budapest; dinner in a wine barrel

On the following day, my brother Brian was due to arrive for a two-week holiday with us, so for the second time within twenty-four hours we were at the airport.

While waiting for the plane to land we went to the small post office on the first floor to get a police registration form for him. (It was compulsory for the place of residence of all visiting foreign nationals to be registered at the local police station.)

The airport building was hot and stuffy, so we joined the people outside on the roof craning their necks for a better view of the plane. The heat shimmered over the asphalt surface as the gleaming jet came into land. The passengers filed on to the waiting bus and we walked downstairs again.

On the way home we asked the taxi driver to stop at a cukrászda and took Brian in to choose some cakes.

The flat was stifling when we returned, the dilemma always being whether to keep the windows closed to prevent the hot air coming in, or to have no air at all. We decided that when it had cooled down a little in the evening we would go down to the river and register Brian's arrival at the police station.

At about six o'clock it was still twenty-eight degrees, but the sun was going down and it was pleasant to be out. The walls of the buildings radiated warmth and we sank into the tar in places as we crossed the roads.

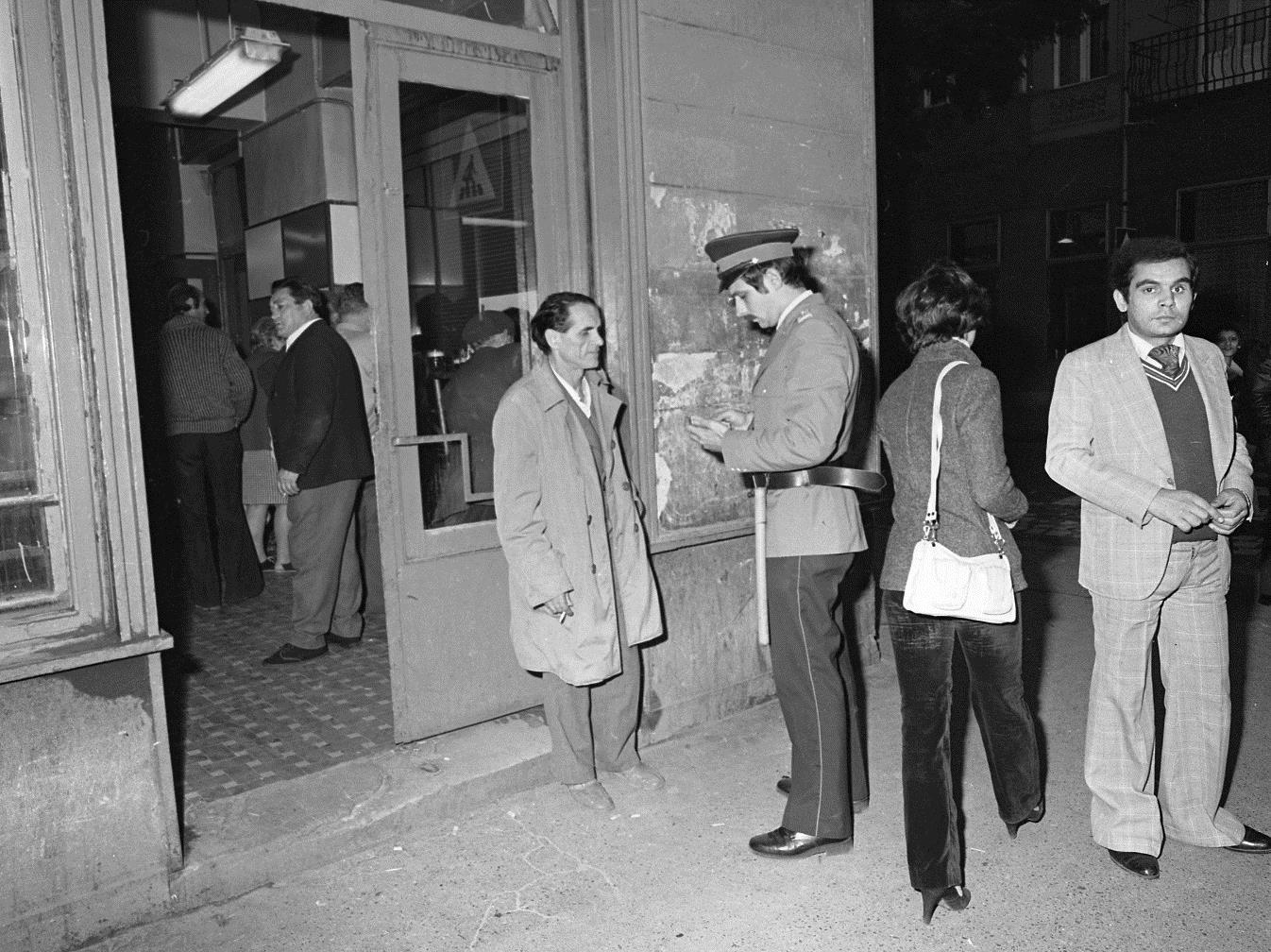

The police station was not far, and a policeman was sitting in the shady entrance on a wooden chair, smoking and reading the evening paper. He looked up as we walked in, handed us a numbered tag and directed us to the door on the right inside the courtyard.

We walked up the few steps, turned to the right and knocked on the door, its pane of glass covered on the inside by a dirty grey net curtain. The office was sparsely furnished with a desk, several wooden chairs, a telephone and a typewriter.

In the corner stood a filing cabinet and above it on the wall a map of Budapest with its districts marked in different colours. Next to that was a shelf with a television set tuned in to a football match.

We had had to forge Zoli-bácsi 's signature on the form since he was still ill and Rózsi-néni was not registered as a tenant of the Garay tér flat.

The policeman hardly glanced at it before stamping it, handing back the visa form and passport and bidding us good-evening.

Closing the door behind us, we heard voices to the left of the courtyard. In the shadows stood a tall, heavily built gypsy handcuffed to a stout policeman.

The gypsy was well dressed, with a white jacket and white shoes, and stood sheepishly leaning against the crumbling wall. The group walked out ahead of us to a waiting police car.

District VII police station Courtesy Fortepan/ Magyar Rendör

Down by the river smartly-dressed couples strolled along the promenade or sat on one of the many chairs and benches, soaking up the last rays of the sun. The mighty Danube flowed quickly by, reflecting the hills on the far bank, the vast building of the royal castle and the spire of the Matthias coronation church high above.

Everywhere along the river were cafés and restaurants, chairs, tables and parasols on the promenade, people chatting, eating, drinking or lazily sauntering past.

Later, after dark, the castle church and bridges would be illuminated, and the many lights of steamers would shine back from the water as tourists and locals lingered outside, whilst lovers and lone fishermen sat on the stone steps leading down to the water's edge and watched the boats go by.

The Danube embankment Courtesy Fortepan/ Zoltán Szalay

Later, standing outside the entrance of Keleti underground buying tram tickets for Brian, and on our way to eat, we heard a voice behind us.

‘Hello, what are you doing here?

’ It was Endre, but before we had a chance to reply he shook my brother by the hand and said, ‘If you're not going anywhere special, why don't you all come with me and have a meal? I'm with a group of Poles on a bus tour, but I'm sure we can find room for you.’

He led the way to one of the car parks by Keleti station. There was a queue of taxis, the drivers sitting either with their doors open and radios on, or standing chatting and laughing with other drivers.

There were students, soldiers and country people carrying enormous loads across the station yard which was full of parked coaches from Poland and Czechoslovakia and one from the Soviet Union.

Endre led us to a rusty green coach with dingy curtains, climbed on and counted heads. One or two were missing: the people who had come to buy and sell in Garay tér.

Those already on the coach were showing one another what they had bought, talking animatedly.

Endre looked at his watch saying, ‘These Poles, always late, always unreliable, they're just like children.’ Then from the far end of the station yard, we saw Kati returning from Garay tér.

She looked heavenwards and shrugged helplessly as she led a straggling group of chattering Poles back to the bus.

A Polish coach at Keleti station Courtesy Fortepan/ Tamás Urbán

There were some free seats on the coach, and no-one seemed in the least concerned about who we were or why we were there.

The coach drove off to their hotel so that Endre could collect the few people who had not gone to Garay, and then we set off for our meal.

Animated conversation and laughter continued as the Poles passed their purchases back and forth over the seat backs for their friends to inspect, while Kati used the microphone to describe the trip.

The restaurant was on the outskirts of the city and had a large garden.

We were met at the gate by the head waiter dressed in traditional folk costume, who led us to tables under the trees.

We all had the same, very good, set meal, during which there was a folk-dance representation of a country wedding. The Poles were also encouraged to join the dance, and after the jugs of wine we had had, they needed little persuasion.

At the end of the meal, having been told we could take our pottery wine mugs home, we once again boarded the coach and headed back into the city. A few of the Poles, hearing us chatting in English, began to sing 'Yellow Submarine' by the Beatles and to call out names of English football teams.

My brother, who knew the names of some Polish players, called them out, and this resulted in much enthusiastic cheering. Then one of the men took out a bottle of some clear spirits from his duffel-bag and insisted we all had a drink.

Conversation was limited, but using Endre's skills as interpreter, we were able to exchange a few words. We were first to get off the coach, and our departure heralded one or two cries of ‘God save the Queen!’ much laughing and much waving.

The following morning, we decided to go to the castle area in Buda. We walked the medieval, cobbled streets and squares, visited the castle art gallery and museum, then made our way down the steep street which afforded glimpses of shady courtyards and numerous restaurants tucked in cellars, and was lined with small souvenir shops full of hand-embroidered blouses and cloths.

The coloured tiles of the Matthias church's mosaic roof gleamed in the sun. Sitting on the turreted Fisherman's Bastion behind it were country people and Transylvanians selling more embroidery and lace.

The panorama over the river to the whole of Pest on its far side, is compulsory viewing for all tourists. The afternoon we spent sitting on a large boat that took a lazy two hours to chug its way around the Margaret island.

Buda Castle area

We had thought of going to a favourite restaurant that evening, called the Borkatakomba (wine catacombs) on the edge of the city. It was a place that few of our friends knew, but all whom we had taken had liked it.

We were just getting ready to leave when the doorbell rang. It was Feri, one of Paul's students from the academy, who had come to see if he could borrow the score of a work he was to conduct but which was unavailable in the Budapest shops. We introduced him to Brian and suggested he might like to come with us to eat.

The bus journey took about forty minutes and we always found it difficult to know exactly where to get off since the entrance was via a car park at the foot of a hill, then through a large wooden door in the hillside itself.

Standing in the doorway was a man in black trousers tucked into long black boots, a shirt with enormously wide embroidered sleeves, and a leather waistcoat. Smilingly, he led us into a dimly-lit tunnel that broadened out into a large cavern. It was noticeably cooler here under the ground, where the catacombs are still used for making and storing wine.

Lining both sides of one long tunnel were huge empty wine barrels turned on their sides. Within each barrel was a wooden table and benches arranged around three sides, so that you actually sat inside the barrel.

The barrel would quite comfortably have seated six people and we piled in and began to look at the menu. Each barrel had a coach lamp attached to the outside which, if switched on, signalled to the waiter. In the cavernous area at the far end were many more tables, and at the very end was a small stage where a gypsy band played and where there was folk dancing.

We switched on our lamp and ordered gulyás. I had once made the mistake of cooking what was called 'Hungarian goulash', from an English recipe for Miklós on his first visit to us in England. Not telling him what it was, I gave him a good helping.

‘Mmmm, this is good,’ he said. I waited. ‘What is it?’ he asked.

‘What do you think it is?’

He considered the question very carefully. ‘Irish stew?’ he inquired.

Even Feri was forced to admit how good the restaurant gulyás was; most Hungarians decry everything but their own mother's cooking.

‘What are you doing tomorrow and Sunday?’ asked Feri suddenly.

‘Well, we don't know yet, it really depends on what Brian would like to see,’ we replied.

‘How about coming with me? I'm going home tomorrow, it's my mother's name-day, so there'll be lots of food.’

‘Well… but how could you let them know, there's no time,’ Paul said, knowing Feri's parents had no phone.

‘That doesn't matter. I've told them all about you, they'll be really pleased to see you. Anyway,’ he continued, noting our reservation, ‘they're used to it. I'm always taking people home.’

The music had begun, and the switch which amplified the playing through a small speaker inside our barrel was broken in the 'on' position. We finished our soup and red wine, looking out of the end of the barrel every now and then to watch the dancing.

No-one was hungry enough to eat a main dish, so we ordered pancakes, a heaped plateful with chopped walnuts and cream and covered with hot chocolate sauce, and some more wine.

The Borkatakomba restaurant

Click here for earlier extracts

Main photo: Ferihegy Airport terminal 1

LATEST NEWS IN community & culture