'An Englishwoman's Life in Communist Hungary': Chapter 4, Part 2.

- 24 Mar 2023 7:17 AM

Now You See It, Now You Don’t and House of Cards have been included as part of the Open Society Archive dedicated to this period in the CEU. You can read a serialisation of them here on Xpatloop. You can also buy the dual-volume book on Kindle as well as in Stanfords London.

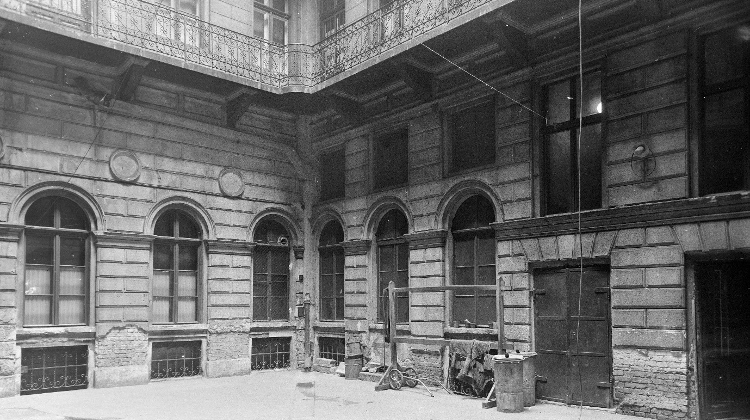

Chapter four: Courtyard and Characters

Part 2 – An unlikely culinary delicacy; a local socialist celebration

I had resumed cello lessons with Zoli and things were going well, although both his and our lack of a phone made arranging lessons difficult. He was nearing the end of his five years at the Music Academy and was considering two major changes in his life - marrying his girlfriend and leaving Hungary to work abroad. He both hated the bureaucracy of the government, and musically felt he would never achieve anything by staying.

The best he could hope for was to play at the opera or in the state symphony orchestra where, as he put it, he would earn just enough to starve on and have to spend every spare minute teaching instead of practising. It was a complaint I had heard many times before.

Towards the end of April an English pianist friend, Danielle, arrived to see us. She had fallen in love with Hungary when she had come to see us in Garay tér. Since that time Ági and Kazi had gone to stay with her in London, and now it was Danielle's turn to be accommodated in their flat up the road.

We were also expecting Sue, Steve and baby Tim to arrive halfway through Danielle's visit, and we had decided that they should squeeze in with us.

It was at about this time that we decided to have a rather belated flat-warming party. Among our old friends we invited Miklós, János, Endre, Caroline, and newer ones like Ági and Kazi and Virginia and József - together with Virginia's Hungarian teacher, Eta.

It provided an opportunity for people who had heard of one another but not met, to do so, and for Danielle to get to know our wider circle of friends. Towards the end of the evening, dark-haired Eta stood on the steps of the gallery and made a surprise announcement: ‘I'd just like to say how much I've enjoyed being here and getting to know some of you, and Pali - my husband - and I, would like to invite all of you to our place, near Ócsa, next Saturday.’

It turned out that Pali was a vet, and he had been made a present of a deer which had been accidentally killed on the road, and Eta was intending to cook us all a venison dinner. We arranged that those with a car should meet at our flat from whence Pali would lead the convoy out to their home.

Thus, the following Saturday, four or five carloads of people turned off the main road to Dabas and bumped their way along the track leading through woodland to an isolated house. Having greeted everyone, Eta led us into their sitting room, furnished in traditional peasant style and with a huge, blazing tiled stove.

While the others were chatting and drinking the homemade pálinka and wine Pali had brought in, I went out to the kitchen. The table was covered with an array of dishes and tureens full of steaming food. I pointed to each, asking Eta for a description of what we were to eat. As I enquired about the third she smiled, a mischievous twinkle in her eyes, and said, ‘Just taste it.

I won't tell you what it is, I'm sure English people never eat it.’ But my curiosity was aroused and I succeeded in persuading her to reveal the identity of the mystery delicacy. ‘Testicle stew,’ she said. I thought I had misheard.

‘What?’

‘Yes, testicle pörkölt, it's very good - do you like kidneys?’ I wrinkled up my nose. ‘Well, then maybe you wouldn't like this either, but give it a try.’

Testicle stew

I was still staring dubiously at this culinary revelation when the others arrived, ushered in by Eta, who took their plates and began to help themselves. As I saw Danielle take a generous spoonful of this improbable gastronomic delight, I wondered whether to warn her, but decided against the possibility of offending our hosts.

We walked through to the sitting-room and I seated myself and happily ate my more conventional fare. I watched her out of the corner of my eye as she swallowed a mouthful of the stew.

‘Good?’ I asked. She considered.

‘Tastes like kidneys,’ she replied, adding ‘Yes, very good.’

I simply could not resist it. ‘Shall I tell you what it really is?’ I asked. She nodded. ‘Testicle stew.’

She stared with new insight at the food in front of her, and then without a word took a large gulp of wine, picked up her plate and disappeared out to the kitchen, soon returning with a new plate of what I had also chosen.

*

Paul worked day and night to get the book version of his thesis ready for publication. He did not put too much trust in the postal service and intended Sue and Steve to take the script back to Cambridge with them. Their letter stated that they would be arriving on March 29th at three o’clock in the afternoon.

We decided that Sue and Steve should sleep in our bed up on the gallery and Tim should have the sofa underneath. We needed to buy another two mattresses for ourselves to sleep on the floor of the small area Paul used as a study. Somehow, everything had been left until the last minute, so we got up early to prepare for the day's main activities - buying the mattresses, going out to the airport, and later Danielle and Paul were going to the opera.

We walked out of the house to the trolley-bus stop. We waited for a quarter of an hour, but no trolley came. Then some people walking past informed us that no public transport was running in the area and Dózsa György út was sealed off while preparations were made for the April 4th parade - the anniversary of the liberation of Budapest from the Nazis by the Soviets at the end of the Second World War.

Memories flooded back in both our minds, of an April 4th celebration we had been to in Józsa, near Hajdúbőszőrmény, where one of Miklós's brothers, János, was the leader of a state farm.

It was the dark, wet evening of a blustery day we had spent with János and his family. The discussion and arrangements concerning the evening were made in Hungarian, we knew only that there was to be some ‘socialist celebration’ at the farm.

When we arrived there, a small crowd of people carrying umbrellas in the unlit lane were making ready to walk on up the road. We dodged the rivulets of water and patches of mud, walking with Miklós at the back of the procession, János having gone to the head, with a wreath in his hands. A short way up the road we turned into a small cemetery, comprising five graves in total, each headstone bearing the red star, hammer and sickle. Together with one or two others, János stepped forward and placed a wreath on each of the graves - the graves of Russian soldiers.

Wreath-laying on Russian soldier’s grave

A few short speeches were made under dripping umbrellas, and then the crowd ambled back down the lane to what looked like a village hall. There we sat on wooden chairs and listened to interminable speeches about productivity and quota fulfilment, after which, outstanding workers were called up onto the platform where they received small bags of money and certificates in recognition of their achievements. It reminded me of a school prize-giving, except for the beer and the red star above the platform.

The mattress shop was on Dózsa György út, so we began to walk hoping we might be able to find a taxi. We were in luck, we hailed the first one which passed, though the driver seemed doubtful that we could drive all the way to the shop. However, we managed to stop in a small side street off Dózsa György and walked the rest of the way.

We were in luck again, they had some mattresses. The shop assistant rolled them up, tied them with string and we carried them out to the waiting taxi. The driver got out of the car and the three of us began to try and force the mattresses into the back of the car. It was impossible. We paid what we owed, groaning inwardly at the long walk home.

The mattresses were not so much heavy as cumbersome, and the string cut into our hands. We had walked about halfway along a deserted Dózsa György út when like a camel in the desert we saw a bus coming from behind us.

We ran as best we could to the nearby bus stop but our hearts sank as we saw the bus was full to overflowing. The doors opened, we took a deep breath and shoved our mattresses into the mass of standing passengers.

Some people were splayed up against the windows, others were pushed onto sitting passengers' laps, but we were on. The bus moved up the road to the next stop and opened its doors. It would have been physically impossible for anyone else to get on. But they were not going to - we had to get off: the remainder of Dózsa György út was closed.

We walked the rest of the way home. I was slightly anxious about the time, the journey out to the airport on public transport was a good hour. Paul decided to make use of the afternoon to continue with his book, so I grabbed something to eat and left.

The airport building was airless and crowded. The plane had just landed and I waited for the first English people to come through from customs. After about twenty minutes no more people carrying luggage bearing British Airways stickers were in evidence. After a further twenty minutes I was worried. I went to the information desk.

‘I'm expecting some friends from England on the B.A. flight, could you check if they were on the plane, please?’

‘I'm afraid we do not have a passenger list,’ came the reply. ‘Wait a little longer,’ the woman suggested. I returned to my seat. Another half hour passed with no sign of any English passengers.

I went back to the information desk, ‘Surely there must be some way of finding out if my friends were on the B.A. flight,’ I began, ‘it's half past four and the plane landed at three. They've got a young child, they don't speak a word of Hungarian and we don't have a phone so they can't contact us. I can't leave the airport until I know if they're here.’

‘Just a minute,’ said the woman, picking up a phone. ‘What's their name?’

‘Kearsey,’ I replied. I waited.

‘Yes, visas with that name have been handed in so they must be here. Why don't you go through to the customs hall and see if they're there?’

‘Am I allowed?’ I asked in surprise.

‘It'll be alright. They must be there.’

I walked self-consciously through the automatic doors as they opened to allow some travellers out. One or two customs officials looked up but I was not challenged. I was surprised to see Lingua's book-keeper in the queue of people at the ‘Something to declare’ desk. I explained what I was doing there.

‘Well, I was on the B.A. flight and I can tell you that there were quite definitely no children on the plane.’ I thanked him and went back. ‘They're not there, and I've just spoken to someone who said there were no children on the flight. Could you check again?’ She did. There were now no visas with their name on. I looked at the wall - five o'clock, I would have to rush home. I wondered what could possibly have gone wrong.

Back at Szinyei utca I ran up to Paul.

‘They weren't on the plane, Tim must be ill or something. Maybe you can try and ring them from Ági and Kazi's after the opera?’

‘I won't be able to go,’ he replied. ‘I'll have to send my book with Danielle instead of Sue and Steve and she's leaving in a week, so I'll have to work.’ Paul changed out of his suit while I quickly pulled on a dress. Danielle would be waiting.

As I ran out of the flat past the letter boxes near the entrance, something caught my eye. I opened our post box to find a letter from Sue sent almost three weeks earlier: they had had to change their day of departure and were arriving the following day!

Hungarian Opera House Courtesy Fortepan/ UVATERV

I ran back upstairs and relayed the information to Paul. It was six-thirty and the performance was starting at seven, Paul changed back into his suit and bolted out of the door. I wondered if public transport would now be back to normal. Then, one hour later he and Danielle appeared at the front door: due to illness the performance had been cancelled.

As I returned to the airport the following afternoon, I hoped fervently that the same woman would not be at the information desk. I was sure she would think I spent my free afternoons scouring the place for non-existent friends, and annoying airport staff. I arrived at three o'clock to find Sue and Steve already waiting - I had forgotten that the clocks had been put forward the previous night, and they had already landed an hour earlier.

Click here for earlier extracts

Main photo: Szinyei Merse utca building’s courtyard - Courtesy Fortepan/ FŐFOTÓ

LATEST NEWS IN community & culture