'An Englishwoman's Life in Communist Hungary': Book 2, Chapter 5, Part 5

- 30 Aug 2024 3:57 PM

Now You See It, Now You Don’t and House of Cards have been included as part of the Open Society Archive dedicated to this period in the CEU. You can read a serialisation of them here on Xpatloop. You can also buy the dual-volume book on Kindle as well as in Stanfords London.

Book Two, Chapter 5

Part 5 – ‘Lomtalanitás’; a communist celebration

As I rounded the corner on my way back home, I saw the first tell-tale mounds of bric-a-brac on the street, reminding me that it was lomtalanítás the following day. Once or twice a year there was the opportunity to throw out those things the dustmen would not take: broken furniture, out-of-order electrical appliances or rusty bicycles, and no longer identifiable items from cobwebbed cellars and dusty attics. We too had planned to rid ourselves of a relic from the bygone age – our Russian washing machine.

Though the machinery was still in perfect working order, its plastic door had split and was emitting increasing quantities of water onto our bathroom floor, threatening in turn to disrupt our peaceful relations with Mr. and Mrs. Kis below. It had not been easy to obtain spare parts for these machines even when they were still imported, but now it was impossible.

The next morning Feri and Robi were due to call in and we enlisted Feri’s help in carrying the heavy machine down to the street. I had made a sign and taped it to the top: In Working Order. Before we had even dragged it as far as the mound of rubbish under the tree on the street corner, a gypsy family with several children aged between about four and ten were assisting us, thereby staking their claim to it.

‘Does it work, then?’ asked the man.

‘Yes, it’s just that the door’s broken,’ I explained.

Without further ado, he picked up one of his smaller children and sat him on top of the washing machine.

‘You stay here, we’ll be back soon,’ he said, and then to an older child, ‘You wait here with your brother.’

The children seemed unsurprised, and did not utter a word. The father ambled off further up the road to inspect another mound while his wife and children, already laden with innumerable bulging, plastic bags, rifled among the clothes and kitchen utensils that lay in the gutter and on the grass verge.

Battered cars, some with trailers, tore around neighbouring streets, scouring for treasures. Meanwhile the two children remained, unperturbed, obviously already old hands. Local papers published the times and location of lomtalanítás around the city, and ‘professionals’ made it their business to be among the first at each, collecting booty either for their own use, or to sell, while a day or two afterwards a council lorry would remove what was left.

An hour or two later as I again looked from the balcony, I saw the father hauling the machine onto a small hand cart which he had brought, and which he pulled behind him with the two children seated in it.

That autumn Hannah joined John’s nursery. She readily adapted to her new surroundings and would probably have been happy to stay beyond lunch, the nap that followed, and into the afternoon; but John refused, and so I fetched them each day after they had eaten.

A strong bond had formed between them, possibly occasioned by, but unarguably strengthened by, the shared language which they used whenever they were together. They almost never argued and would play together for whole days, resenting as interference any suggestion that they might like to see anyone else or play with other children. Indeed, birthday parties were embarrassing events where John and Hannah isolated themselves from the other children to play together, though their knowledge of Hungarian was now more than adequate to join in the others’ games. They became inseparable.

At the beginning of November, I received a phone call from Miklós. ‘You can come on the seventh, can’t you?’

‘Of course,’ I replied.

‘Everyone will be here, I’ll be cooking. About seven o’clock.’

The national holiday of the seventh of November, the anniversary of the Russian revolution, had been abandoned along with others of its kind at the first opportunity after the revolution that had superseded it. Though marked by celebrations and processions in Moscow, it had remained something of a non-event in Hungary, where the happenings it commemorated were, unsurprisingly, not viewed with quite the same degree of enthusiasm as by its neighbours.

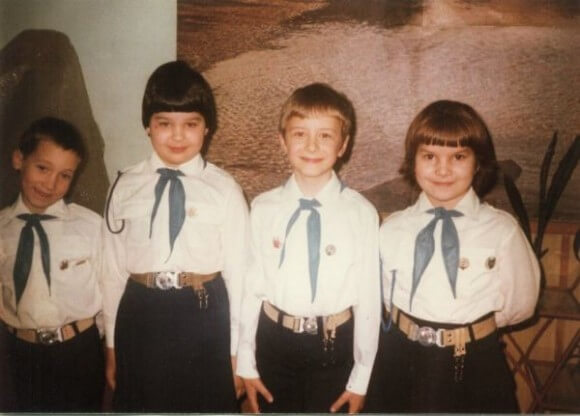

However, the many socialist songs children had sung in their Pioneer (akin to the Boy Scouts) meetings and summer camps were regarded with some nostalgia by many of the generation that had learnt them at school. Miklós had initiated a tongue-in-cheek celebration every November, and those invited would bring communist paraphernalia to decorate his Rákóczi tér flat. They usually arrived adorned with any medals that had belonged to family members, bearing such inscriptions as ‘Outstanding Worker’, and the neck scarves they had worn as Pioneers. Following the eating and drinking, and sitting below pictures of Marx and Kádár, red stars and flags, they began to sing songs about the march to socialism, with ever-increasing gusto.

All schoolchildren belonged to the ‘Little Pioneers’ movement

This annual parody had by now become a tradition in the large circle of Miklós’s friends. It also offered an opportunity for those of us who had once met regularly to see each other. In the days when unemployment had officially branded you a danger to society and the state, we seemed to have had an immeasurable amount of leisure. It was unnecessary to work many hours to earn the uniform monthly wage of three thousand forints, which easily covered all living expenses from food and travel passes to electricity, gas and telephone charges.

Rents for a state flat were nominal, thus only those with ambitions to own a car or build a house considered doing much extra work. It was also true that in a society where everyone felt their paltry salary hardly deserved more than their (occasional) presence at their workplaces, any additional work – or a second job as it was called – was often done during normal working hours. In many instances it was quite simply a case of doing as little as one could get away with.

A combination of these factors - a minimum of work, enough money to spend on cafés and cinemas, and the fact that few people had telephones and thus contact could only be maintained by meeting personally - meant that many people’s evenings were spent in exactly this way.

Unemployment was now endemic, as was inflation – visits to the local supermarket always saw price increases. The cashiers could no more keep track of prices than their unhappy customers. It became one member of staff’s full-time job merely to print and stick new labels on top of the thick wad of existing ones. People were now working their eight hours and had no choice but to take on any extra opportunities they could to supplement their incomes – not now to try and buy a car, but to pay their bills or for their children’s school books.

Most people by now had telephones with which they could ring their friends, but did not have time, energy nor spare cash to engage in a social life they had previously taken completely for granted.

Thus, when the door of Miklós’s flat opened, I beheld a room full of friends I had not seen for months, or in some cases, since the previous year’s party. The question ‘How are you?’ was universally greeted with a shrug and the words, ‘Very busy.’

Without exception teachers, librarians, translators and the like were managing to continue the work they had always done, though all confessed to being forced into a degree of ‘prostitution’ to make ends meet. I myself had sat in a studio to record texts written in appalling English, and whereas in the past those undertaking such work would spend hours correcting and editing the script – which someone else had already ostensibly done – we now demanded payment for such a time-consuming task.

This was usually not forthcoming, in which case we recorded the nonsense we had been presented with, pocketed the fee for the time spent in the studio, and left. No-one could now afford to give freely of their time for the sake of quality. It was also true that an open discussion of money matters, something that had caused not the slightest embarrassment when a fixed state salary was almost universal, was now not possible. People’s earnings, along with their political persuasions, had become prickly subjects.

Tom and Donát, students from our days of Lingua courses in Baja, had driven specially from this town on the Yugoslav border in order to celebrate November 7th.

‘Have you heard anything from Nick?’ they asked me.

‘No. Haven’t you?’

‘I don’t think he can buy that house in Dunafalva in his own name. It’s not possible for foreigners yet to buy property in Hungary. Do you own your flat?’

I explained the unlikely string of coincidences which had enabled us to buy our apartment, adding that it was still not officially registered in our names.

‘We’ll have to buy it for him – and it needs lots of work done on it. Did you see the photographs?’ Tom asked.

I had seen them, though they only showed the outside.

‘We’ll ask Nick to come over at Easter and sign some papers and then we can start doing some work on the house. Do you think he really wants to come and live here, or just use it in the summer holidays?’

‘No, I think he’s planning to live there,’ I replied. ‘He’s got no-one and nothing in London – Danielle says he hasn’t given anyone his address, she thinks because it’s such an awful place. He’d be really happy to leave. Do you think he could find some work in Baja?’

They were certain that as an English native speaker the local schools would be more than ready to offer him work, and that they themselves would make use of his knowledge of computers.

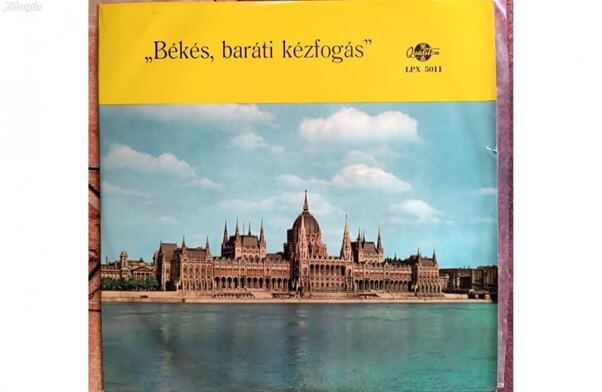

“Peaceful, friendly handshake” – communist songs

Our conversation was now cut short as the volume of the singing drowned all else. A crackly cassette tape was playing full volume to the choral accompaniment of more than fifty slightly inebriated revellers wearing an assortment of medals and scarves and holding duplicated song sheets – though the majority could remember the words without help. Despite the noise, however, we soon became aware of the continuous ringing of the doorbell.

‘Oh no,’ said Miklós, as the singers tailed off and someone lowered the volume on the cassette recorder. Officially, these songs were now banned, along with the sentiments they expressed.

Outside the door stood one of Miklós’s neighbours, flanked on either side by a policeman. They walked in.

‘We received a telephone call complaining about the noise coming from this flat,’ said one of the two policemen.

‘Yes, we’re having a choir practice,’ Miklós explained, indicating the rows of rather sheepish carollers.

The three men looked in disbelief at the unlikely group and at the pictures of Lenin and other communist memorabilia decorating every wall.

‘Well,’ continued the first policeman, coming further into the room and looking around, ‘I would like to ask this kindly group of singers to keep the volume down.’

He walked back to the front door where his colleague still stood, followed by an obviously dissatisfied neighbour, who nevertheless could not bring himself to voice his true complaint, which was not about the volume of the singing but about the songs themselves. Ignoring Miklós, he disgruntledly muttered goodnight to the policemen and wandered back up the dimly lit stairway. The police hung back slightly, and we all waited silently for what threats or admonishment might yet be meted out to us.

However, stealing a look at Miklós’s medal of Outstanding Worker, and another at the red star that graced the toilet door, he saluted us all.

‘Good night, comrades,’ he said quietly, ‘and enjoy your party.’

Medal ‘For outstanding work’

LATEST NEWS IN community & culture