'An Englishwoman's Life in Communist Hungary': Chapter 4, Part 7.

- 27 Apr 2023 12:55 PM

Now You See It, Now You Don’t and House of Cards have been included as part of the Open Society Archive dedicated to this period in the CEU. You can read a serialisation of them here on Xpatloop. You can also buy the dual-volume book on Kindle as well as in Stanfords London.

Chapter four: Courtyard and Characters

Part 7 – A trip to the opera; another move looms

It was with such thoughts in mind that I walked down Szinyei utca towards the underground one evening on my way to the opera house where I would meet Paul and Laurence. We had tickets for a performance of Mozart’s Cosi fan tutte.

We usually bought tickets for the upper circle since there was an excellent view from the centre seats and at twenty forints it could be regarded as free. Having made our way through the side entrance and up the many flights of stairs we arrived in the beautiful red plush and gilt surroundings of the third-floor café‚ and cloakrooms.

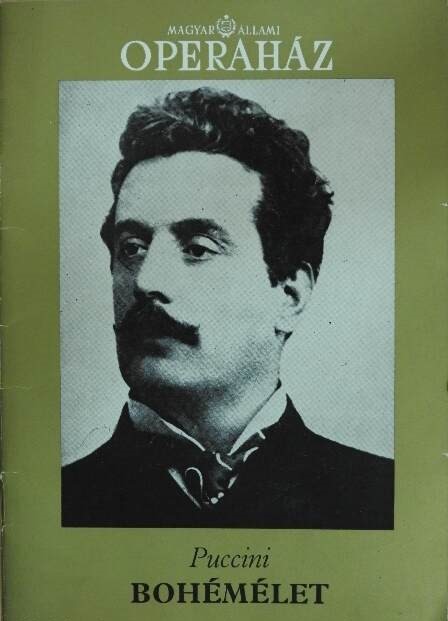

Paul and Laurence had no coats, but I handed mine in, pocketing the ticket. As we strolled towards our seats I glanced casually at a pile of programmes the usherette had left on her chair by the door. The picture was of a garret scene, the title, La Bohème. I nudged Laurence and pointed at the programmes,

‘What's she doing, selling Bohème programmes?’ I asked.

Then we heard our answer as the usherette spoke to another member of the audience while she examined his ticket, ‘Yes, it's Bohème tonight - lovely opera - due to illness they can't do the Mozart, lovely opera Bohème ...’

Laurence wasted no time. ‘Is it La Bohème tonight?’ he asked her.

‘Yes, lovely opera...’ she began before Laurence interrupted her.

‘But I haven't come here to see Bohème. I bought tickets for Cosi fan tutte,’ he said.

‘But it's such a lovely work...’ she repeated pointlessly.

La Bohème programme

We had seen it many times. It was not as though we had wasted much money on the tickets, but it was disappointing.

‘Come on,’ said Paul, ‘we might as well see it now that we're here. After all,’ he said, mimicking the usherette, ‘it's a lovely opera...’.

It was good, not surprisingly really, considering that the Opera House operated no system of using substitutes for the major roles, so if someone was ill, the standby opera was always La Bohème, the equivalent for a cancelled ballet performance, Swan Lake.

When the opera ended I joined the throng jostling to reach the counter by the cloakroom to reclaim their coats. I rummaged in my pocket for my ticket, it wasn't there. I felt in my other pocket - nothing. I knew I had not put it in my bag, but I searched there also. No luck. I walked over to where Paul and Laurence stood chatting.

‘I didn't give you my cloakroom ticket, did I?’ I asked Paul. He shook his head.

‘Oh dear, have you lost it?’ asked Laurence. ‘Let's go back and see if it's where we were sitting.’

We searched under the seats in our row and the ones in front and behind, but in vain.

‘How will I get my coat back?’ I asked.

‘Don't worry,’ replied Laurence. ‘We'll hang about till nearly everyone's gone and explain the situation,’ he said, leading the way back to the cloakroom.

There were still a few people at the counter, returning opera glasses and putting on their coats. Few garments were left on the hooks behind and I could see my coat quite clearly. Laurence approached the cloakroom attendant.

‘My friend here has lost her ticket...’ he began,

‘Then I can't help you,’ the woman interrupted curtly.

‘But I can see it,’ I said, ‘that one over there.’ I pointed.

‘Without your ticket I can't give it to you,’ she said, automatically taking the tickets from someone else and fetching his coat.

‘Look,’ said Paul to me, ‘we'll just wait until all the other coats have gone and then she will know it's yours.’

We stood in silence, waiting until the last of the audience had strolled away, but the woman ignored us and began to gather up her own belongings in preparation to leave.

‘Look,’ I said in desperation, ‘my coat's still there, no-one's claimed it, and everyone's gone home, who else's could it be?’

She continued putting on her own coat and scarf as though she had not heard me.

‘Don't you remember what number was on the ticket?’ she asked, without so much as looking at me.

‘No.’ I had to admit.

‘Well, how do I know it's yours then?’ she asked.

‘Who else's could it be?’ asked Laurence, impatience now much in evidence in his voice.

‘Maybe you dropped it where you were sitting,’ she said.

‘We've looked,’ said Paul.

‘Isn't it in your bag?’ she asked, as though I wouldn't already have checked there.

‘No, it's not,’ I replied. She sighed.

‘We're not leaving until we get the coat,’ said Laurence.

Had the woman gone home, we could have helped ourselves. If it had been a valuable mink I could have understood it, but it was just an old, corduroy jacket. She walked towards it, took it off the peg and unpinning the ticket plonked it in front of me. Then, without a word she picked up her bag and walked off.

Some days later we were sitting in our flat having our evening meal with Laurence when there was a knock on the front door. Paul went to open it and we heard him saying, ‘Hallo József, come in.’ It was our landlord. He usually only came for the rent and had been just the previous week.

Paul introduced him to Laurence while I cleared away the plates to the kitchen. ‘We're thinking of selling the flat,’ I heard József say as I returned with the coffee, ‘and I wanted to give you time to find another place and let you know that we may bring people interested in buying it to see around the place.’

My heart sank. Although I wasn't particularly keen on Szinyei utca, nor this particular building, I liked the flat now and the idea of moving again was unappealing. Maybe even the actual move would not be so bad, but to find a suitable flat we could afford might take months.

We did not want to live out in the suburbs, and we needed a place which had plenty of space for all our records, books and other belongings. Before moving to Garay tér we had been to see one or two flats belonging to people who were going abroad for a year, but they were crammed full with their own things and we would have had nowhere to put ours.

We agreed to try and move out at the beginning of September, but taking away the six weeks we were to spend in England, this did not leave us a lot of time.

The following Monday morning at eight o'clock I made my way up Szondy utca to Ági's and Kazi's. I taught them regularly since they both needed English in their jobs. As I turned into the gateway of their building Ági caught up with me, she had just taken the children to school a couple of streets away.

‘How are you?’ she asked.

‘Fine,’ I replied, ‘but just imagine, we have to leave our flat, the landlord wants to sell it.’

‘When do you have to move?’

‘At the beginning of September,’ I said.

We walked up to the first floor. She let me in through the glass doors which opened onto a small area off which three doors led into three flats. Once there had been only one flat here and these glass doors were the private entrance to the huge apartment which lay within.

It had belonged to Kazi's family, and his elderly aunt still lived in a part of the original flat, now separated off and with its own entrance to the left of Ági's and Kazi's. The third door led into what they told me was a tiny flat occupied by a young couple with two children.

In the 1950s the state appropriated all privately owned land and property, ‘nationalising’ it, and then proceeded to lay down new rules for how many square metres of living space must be occupied by what number of people. Thus, Kazi's family, like so many others, were forced to either leave or partition their large flats, or have the state foist total strangers on them to share their living quarters.

We walked inside. Kazi was waiting for us. ‘Sorry, I can't stay this morning. I have to go into the office early - I'll see you next week.’

‘You go in and sit down,’ said Ági, ‘I'll come in a minute.’

I walked into the huge sitting room. It was very imposing with its antique furniture, oil paintings and various objets d'art. The atmosphere of middle-class grandeur had survived the age which had sought to destroy it.

I picked up the newspaper lying on the table, it confirmed my suspicions: although I might now be able to communicate reasonably in Hungarian, my knowledge was still no match for a newspaper.

Ági returned bringing two cups of coffee and sat opposite me on the Biedermeyer chair. ‘So, what have you been doing this week?’ I began, settling down to my coffee.

‘We've got some exciting news!’ she said animatedly. ‘It looks like we are going to Brussels for a few years.’

‘When?’ I asked in surprise.

‘Probably in August, so that the children will be able to start school at the beginning of September.’

‘Will they go to a French-speaking school?’ I asked.

‘Yes. Perhaps I'll try and find someone just to teach them a few basic things before we go.’

Ági went on to explain that the job, trade secretary at the Hungarian embassy in Brussels, would be hers. They would be given accommodation, the children could learn a second language, everything was perfect except for one thing.

Kazi would have no work, in fact he would have to take care of the children and the household because Ági would be expected to work even if the children were unwell. At most, he could do some private business from home, or maybe, she added, he would work towards an M.A.

‘And I've just told Kazi about your having to move, and we think you should come and live here,’ she concluded.

I was flabbergasted. The thought had not occurred to me. We could never afford the rent for this flat of over one hundred square metres and they could easily find a wealthy foreigner who would be only too keen to rent it. I pointed out the obvious flaw in her plan.

‘But if you don't come here, we are not going to rent it out. We'd already decided not to, it's not worth the risk even for a high rent of having the furniture or other things damaged.’

‘But we could hardly afford to pay you more than we're paying now,’ I said.

‘No problem,’ she concluded. ‘Talk to Paul about it. The only thing is that we will spend most of July and August in Hungary, so we would like to have the flat then, but you wouldn't have to pay rent for these two months.’

And so it was that our problem was solved. More than that - we would have a beautiful flat near the park with a telephone and a working automatic washing machine, for the same rent as the Szinyei one.

Ági and Kazi’s building

Click here for earlier extracts

Main photo: Budapest Opera House

LATEST NEWS IN community & culture