'An Englishwoman's Life in Communist Hungary': Book 2, Chapter 1

- 8 Sep 2023 8:25 AM

Now You See It, Now You Don’t and House of Cards have been included as part of the Open Society Archive dedicated to this period in the CEU. You can read a serialisation of them here on Xpatloop. You can also buy the dual-volume book on Kindle as well as in Stanfords London.

Book 2, Chapter 1: Changes

Part One – Moving on: a new flat, a new era

I did not want to move.

I stood in the middle of the lofty, stucco-ceilinged sitting room, its oil-painted faces overseeing our activities from their dusty canvases. I stared vacantly at a sea of half-packed cardboard boxes strewn on Persian rugs and Biedermeier chairs, the piles of newspapers on the marquetry table, and tried to blot out the characterless images of the flat we would soon have to call home. In the far corner, next to the walnut bookcases, Paul sat engrossed in the newspaper with which he should have been wrapping crockery.

‘Oh, come on,’ I said, ‘we’ll never finish packing if you’re going to read all the papers, and the children will be awake soon.’ But he could sense the lack of purpose in my tone, the total absence of will to see the job done, and thus continued reading.

Sighing, more with dissatisfaction at my own inability to summon up some self-discipline than with annoyance at Paul, I approached the window. Though the relentless July sun had long since passed its shuttered panes, they remained tightly closed.

Through the chinks which still allowed dusky rays of warm light to trickle into the room, I could see the cement mixers lined up in the street below. Clouds of grey dust obscured the view of the building site, while the jarring noise of drills drowned even the continual roar of traffic along the broad avenue of Dózsa György út.

A small mound of bricks and plaster was piled at one end of the crater - all that remained of the Chimneysweep restaurant over whose loose orange tiles we had daily surveyed the view to Heroes’ Square and the Botanical Gardens, and whose gypsy music and singing customers had serenaded our children by night as they fell asleep.

There was a soft knocking at the front door. I picked my way over the stacks of still unpacked books and records and was greeted by our neighbour Cili, who was already standing in the dark hall.

‘I didn’t want to ring the bell, I thought the children might be asleep,’ she said.

‘They are,’ I said.

‘How are you getting on?’ she asked, looking through to the sitting room beyond.

‘Come and see,’ I said, leading the way.

Paul looked up from his paper as we entered the room.

‘Cili’s come to see how we’re getting on,’ I told him.

‘I can see,’ she grinned. ‘Look, when the children wake up, bring John over and he can play with Dani. I’d love to have Hannah too, if you can get on better without her.’

I smiled and touched Cili’s arm in thanks. I would be at least as sad to leave her as I would the flat itself. Although a month younger than me, she had somehow represented the older sister I never had, to whom I could always turn for practical advice or help.

I had been pregnant with John when we moved into this flat three years earlier, a fact which had delighted Cili, since her younger child Dani was already a toddler and she looked forward to a new child ‘to baby.’

It was Cili who had visited me daily after John’s birth, able to walk brazenly past the hospital porter whose sole purpose seemed to be to stop visitors from entering outside the very limited hours permitted.

In her white chemist’s coat he took her for a doctor and she was never challenged, which enabled her to bring me both food and her cheery presence. And it was Cili who had looked after John following Hannah’s birth, no small feat with a child who was oversensitive and prone to howl with alarming regularity. She took all this in her stride.

When Cili left, I returned to the sitting room. I knelt on the floor amidst the bags of bedding and the as yet unused newspapers. Next to me stood a large cardboard box bearing the inscription: Pickfords, no.24: Clothes and Sundry.

This was just one of the original twenty-six boxes with which we had moved to Hungary in 1982. They had accompanied us through the seven years and five flats of our lives in Budapest, from the cockroach-ridden cellars of Garay tér to the grandeur of our present home. I wondered how many more times we would need to use them.

I sighed again. We could be nothing but grateful to Tamás, a violinist and a student of Paul’s at the Music Academy where he taught, when he had offered us his brother’s flat. We had nowhere else to go and no time to look.

When we had first realised our predicament we knew Tamás would probably be able to help, with his seven siblings and vast array of aunts and uncles, many of whom we knew. The new flat belonged to his eldest brother, a hospital doctor, who lived outside the city and had bought it as an investment, never intending to live in it himself.

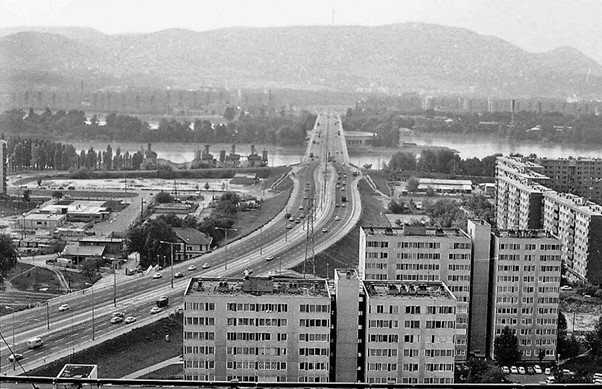

Our ten-storey block on the Pest side of Árpád bridge

Paul first visited the ninth-floor flat alone with Tamás. He had been suspiciously non-committal on his return, saying he was sure it could be made homely, and that here at least we could look forward to staying for as long as we pleased, since - unlike in all our previous flats so far - it was not a case of friends being abroad and our having to leave upon their return.

The friends from whom we had rented this flat for the past three years were returning from Brussels. Two days hence the decorators would precede their arrival, to completely renovate the elegant but shabby rooms we now occupied.

Paul’s reticence regarding the new flat was finally broken when he was forced to tell me that we could not move in until the end of August.

The flat had been let to a medical student from Libya who had done a midnight flit, not only leaving the kitchen and bathroom in a state warranting fumigation, but with an outstanding telephone bill of several hundred pounds.

It would therefore take a month to clean and repaint. Unbeknown to me, Paul had contacted the family whose three daughters I taught English, and whose house we had looked after the previous summer when they had spent a month in Greece. As luck would have it they were going away again, and were delighted to have us tend the garden and feed their pets.

This necessitated some detailed packing: those items we would need in the next month - including John and Hannah’s cots - separate from those things which could be taken straight to the new address.

A quiet, pleading call emanated from the far end of the flat.

‘Mummy....mummy.’ I walked out of the sitting room and on through our bedroom to the children’s room. John was standing up, arms outstretched.

As I lifted him out of his cot, warm and sweaty from the July heat, I glanced across at five-month old Hannah, still blissfully asleep. Friends had called it an act of faith to have a second child less than two years after John, who had so completely transformed our lives.

Not even our doctor friends could explain his apparent lack of need for sleep, which was unfortunately not matched by our own. We had tried to console ourselves with the baby books which reassuringly stated that a child who is awake is learning.

Yet it was difficult to find much succour in this when we were, as usual, being woken for the seventh or eighth time that night. But Hannah was different: she rarely cried, she was sunny and contented, and most of all she slept, anywhere, any time, oblivious to any noise or disturbance.

The telephone rang in the sitting room. Paul picked it up and waited to see if the call was for us.

The phone sounded simultaneously in both our and Cili’s flats, and whoever answered first could hear the caller. If it was for the other flat you simply replaced the receiver and the caller was automatically put through.

This was a variation on a ‘party line’ system, endured by most people lucky enough to have a telephone at all. It meant, of course, that if your ‘twin’ was using the phone, you could not, and whereas we knew who our partner was, most people’s ‘party’ was completely unknown to them.

This posed particular problems if they did not replace the receiver properly because you could not use the phone until they did. It was also usually necessary to make several calls to the Post Office and wait several days before a defective line was mended.

In addition, it was almost impossible to ring anyone if it was raining - the lines became water-logged. I had once succeeded in reaching someone in Pakistan on a rainy day when trying to ring a friend in Buda!

In spite of all the shortcomings, however, a telephone was a major selling point in a country where only around ten percent of households were equipped with one.

A telephone, though, belonged not to an address, but to a person, who could take both the apparatus itself and the line with them if they moved. Flat advertisements never failed to mention the attraction of a telephone, even if they could merely boast that installation was due within the year.

It was Kazi, the owner of our flat, who had rung to confirm that the decorators would be arriving on Friday morning. His call provided the necessary impetus to finish packing the remaining kitchenware, after which Paul dismissed me with the children to Cili’s, while he continued to put books in boxes.

Cili’s flat was minuscule, some thirty-two square metres in all. I had spent many happy afternoons in her kitchen helping her work towards the intermediate state exam in English, tasting her culinary experiments or drinking her parents’ home-made wine.

She and Laci were also planning to move, to a larger flat in a neighbouring street, having long ago outgrown their living quarters: outside their front door tricycles were suspended from hooks in the wall, baskets of vegetables balanced uneasily on bags of indeterminate content, Wellington boots and skates stood crammed behind makeshift shelves which provided an extension to their kitchen, while the smell of freshly-cooked pörkölt or cakes filled the air.

Apart from their entrance and ours, a third door opened onto this small, stone-floored area with its glass doors leading to the main stairway and other flats beyond. This door belonged to Marietta-néni, Kazi’s aunt, now around eighty years old.

She still worked as a physiotherapist, the only possible explanation for her youthful agility if not her continued interest in all around her. The previous winter she had slipped outside the hospital where she worked and broken her elbow. I called in to see her the following day.

‘I’m just going to the shop, can I bring you anything?’ I had asked. ‘Bread, cheese, fruit…?’

‘No, nothing healthy,’ she interrupted in her deep, croaking voice, ‘just bring me some cigarettes and some ham - none of that lean stuff, something with plenty of fat on it. Do you know,’ she added brightly, ‘I’m busier now than I was at the hospital. My patients ring me at home and I have to tell them what exercises to do.’ She laughed.

Before she could see me out her phone rang and she hurried to answer it, stuffing some money into my hand and leaving me to close her front door.

A well-to-do family flat in Budapest Courtesy Fortepan/Albin Schmidt

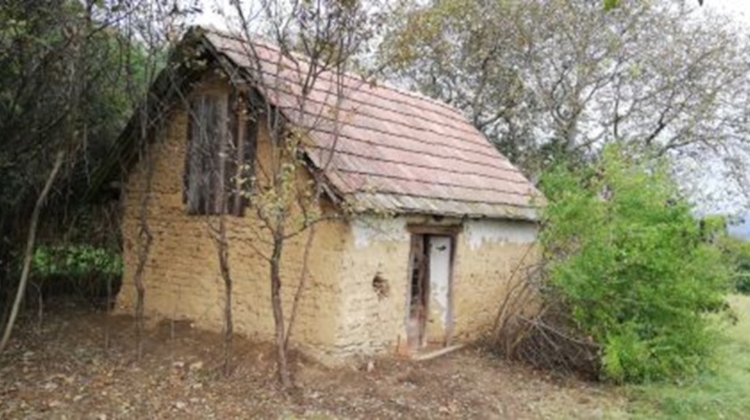

There had once been just a single door here, and only one, vast, elegant apartment within: well over two hundred square metres of antiques and oriental rugs, German-speaking maids, and a conservatory full of palms overlooking the art galleries and the City Park beyond.

The years after the war, however, had brought unimagined changes, and in an effort to eradicate such obvious signs of wealth and privilege, the owners of such large flats had been forced to partition them. Yet the atmosphere of timeless elegance, albeit decayed, persisted within their new confines.

It had been reduced, but not destroyed. And now another momentous change had come about - the end of the one-party state, the end of forty years of communism in Hungary.

Although in retrospect one could probably now point to some small signs of liberalisation as early as the previous year, the actual speed of those changes, the momentum with which we had been hurtled towards the final scene, had been dizzying.

But what was stranger still was not that a régime which had seemed cast in iron had disintegrated swiftly and silently, but that there was now a vacuum in its place, the tangible tension of a nation holding its breath, waiting to see what would follow.

A maid – most well-off families had one Courtesy Fortepan/Albin Scmidt

By late Thursday afternoon our lives and our memories had once again been neatly packed into twenty-six large cardboard boxes. The old grand piano we had borrowed from a sister of Tamás, and which had been heroically manhandled up from the street by a number of his siblings - including one who was a priest - awaited its return journey.

That night, with Paul and Hannah fast asleep, the drill silent and only the swoosh of cars on the road left wet from the storm, I sat with John in the sitting room.

Gently I stroked his face as he lay in the crook of my arm, and listened to the authoritative tick of the beautiful eighteenth-century gilt clock on the wall beside me: a clock which had seen two wars and a revolution, the tanks rumbling past below along Dózsa György út, and the division of the flat.

It had witnessed the arrival of new children - including our own - and the departure of the aged. Its hands, which had marked their way through history, were now sweeping us into a new era of which we knew nothing, but of which so many had so much hope.

Click here for earlier extracts

Main photo: Our house on Dózsa György út

LATEST NEWS IN community & culture