An Englishwoman's Life in Communist Hungary': Book 2, Chapter 3.

- 18 Jan 2024 8:48 AM

Now You See It, Now You Don’t and House of Cards have been included as part of the Open Society Archive dedicated to this period in the CEU. You can read a serialisation of them here on Xpatloop. You can also buy the dual-volume book on Kindle as well as in Stanfords London.

Book 2, chapter three: Neighbours

Part 4 – Somewhere to call home; new permits

There was one flat I had overlooked, in Zugló, not far from the little old underground – the first to be built in Europe after that in London. It sounded the right size, and when I looked on the map it transpired it was close to the City Park. An elderly man answered the phone and suggested we go and look at the flat the day following.

An olive green building stood on the corner of two roads. Even given my fairly limited knowledge of architectural styles it looked as if it had been built in the 1920s. Acacia, horse chestnut and maple trees surrounded it, and a row of rose bushes lined the front fence.

An elderly woman was bent double weeding but greeted us as we opened the garden gate. The battered front door led into a cool stairwell with wrought iron banisters. The flat we were to see was on the second floor, and as we trudged up the more than sixty steps, we realised the flats must have high ceilings.

Mr. and Mrs. Ács met us at the door, a couple probably in their seventies. The flat, though not as old as some we had occupied in the centre of town, had the familiar double doors, the almost four-metre-high ceilings, the heavy furniture and brass door handles, the antiquated wiring and crumbling plaster.

There were three large rooms, one with a balcony akin to a tree house, the acacia’s branches brushing its railings and shrouding it totally from the road below. There was also a small room, once the maid’s, leading off the kitchen and which Paul immediately claimed as a potential study.

Two rooms and the kitchen faced south-west and had a view of the Buda hills, while those on the other side faced a large garden on the opposite side of the road, with more trees and benches, thus not a single room was overlooked by another building.

View of the Buda hills from the flat

‘We don’t want to leave,’ said Mr. Ács. ‘We’ve lived here for thirty years but our sons have grown up and gone and it’s too large for just the two of us.’

‘And the flat needs renovation,’ added Mrs. Ács, ‘and we can’t afford that on our pensions.’

Mr. Ács took us down into the garden to show us the garage. ‘Yes, it’s quite a good size,’ he said.

‘And it seems to have a new roof,’ Paul observed.

‘Yes, but the new one leaks a bit – here,’ he said, indicating a small damp patch. ‘The old one never leaked.’

We were amused at his sincerity.

‘And of course the railway’s a bit noisy,’ he went on, ‘though you get used to it, and it’s not such a busy line.’

It almost seemed as though he were trying to put us off the flat, but he obviously knew no other than an honest approach. We also saw the cellar, light and dry, each flat having a separate, generous storage area.

After leaving we strolled along the neighbouring streets to get a better picture of the surrounding area: the old villas were interspersed with less attractive concrete buildings from the sixties; chickens scratched the dust in the garden opposite where a dog lay by the front gate; the roots of old trees had misshapen the pavements, and creepers spilled over fences and garden walls; pock-marked façades bore witness to a war, a revolution and forty years of indifference; and everywhere were trees, shades of green softening stone and tarmac, emerald hues shading crumbling ochre villas, mud-splashed ivy concealing slumbering cats, and wood pigeons cooing from above the sour-cherry and apricot trees.

We discovered a small post office in the most bullet-ridden house. A local restaurant had its tables in the garden, and there was a cukrászda, a cake- shop-cum-café, next door to it.

The City Park was just the other side of the railway embankment, though such a jungle of overgrown bushes lined it that the tracks were rendered invisible. Small, grey lizards sunned themselves on hot garden walls and scurried into cracks when John tried to touch them. He shrieked in surprise at their speed. A cockerel crowed from a distant garden, and a tram rattled past to remind us we were still in the city.

‘You can’t buy the first flat you see,’ a friend said later that same evening, as I poured forth my enthusiasm. ‘Most people spend a year looking before they find what they want.’

‘But I have found what I want!’ I interrupted. Paul was more circumspect. While I paid a second visit to Zugló, he drove to Nagykovácsi and other small villages beyond the city boundaries, now convinced that we should move out of the centre. I, however, remained adamant that the Zugló flat combined the peace of a leafy suburb with the convenience of good public transport – it would take just twenty minutes of travel from our front door to be standing inside the Music Academy.

We made a third visit to Mr. and Mrs. Ács to state our intention of purchasing their home, relieved to find that as yet no-one else had taken a serious interest in it. We were totally ignorant as to the procedure for buying property, not just in Hungary but also in England. We decided to consult István, a friend who had taught at the University of Law.

In fact, the process was quite straightforward, unless you were a foreigner. As yet, there was no law permitting non-Hungarians to buy property, and so István recommended we apply for permanent resident’s status forthwith.

The police station was just on the left of Népköztársaság útja Courtesy Fortepan/Anna Krizsanóczi

Paul set out for KEOKH – the state office dealing with foreigners – housed on Andrássy út in a police station. An officer stood in the doorway, a large crowd of people, papers in hand, milled around in front of him. Not realising who they were or what they might want, Paul pushed his way towards the man on duty.

‘I’d like to get a resident’s permit,’ he said.

‘Yes,’ replied the policeman, already indicating he should queue to the side with the others. ‘Nationality?’ he asked routinely.

‘British,’ replied Paul.

‘You what?’ he spluttered in disbelief. ‘British?’

Paul had to produce his current temporary permit to prove the point, whereupon he was given a numbered aluminium tag and told to go to the first floor, the guard staring vacantly behind Paul as he entered the building.

Over the years we seemed to have spent countless hours in such buildings: floors of echoing corridors with tightly closed, forbidding doors, devoid of any indication of what lay within them.

Ragged queues of tense, silent people embroiled in a bureaucratic process which even those administering it would have been at a loss to explain: a bewildering array of documents to be shown but which were never sufficient, entailing yet another sojourn in the building, and the strong likelihood that the official one had seen previously was not there today, thus necessitating a fresh start.

Each door had a hand-scribbled notice in several languages warning those in the corridor not to knock but to wait until called, while no sign of life emanated from within. Without a single chair, those forced to spend many hours there sat on the cold floors, while others with forms to fill in did so leaning against the walls.

Occasionally, one might catch a tantalising glimpse of an official-looking figure slipping into a room further down the corridor, but this very unexpectedness meant that those waiting were seldom quick enough to accost him and ask for information.

Paul walked slowly back and forth along the corridor, hoping against hope that the change in political system would have brought about some equivalent change in bureaucratic procedures, and that some small notice would indicate which of the many rooms he should queue up outside.

It was then that he became aware that many of those people sitting on the floor, lining the hallways, were quietly speaking Hungarian. Of course – the Transylvanians who had taken their long-awaited opportunity to ‘return’ to their homeland following the execution of Ceausescu. This then explained the reaction of the policeman who had obviously been besieged by hundreds of ethnic Hungarian-Transylvanians since January, seeking residency in Hungary.

Paul finally decided to risk the potential wrath of those in one of the offices, and knocked at a door. As he walked into the room he was greeted with hostile stares, but pre-empting their inevitable rebuffal of his request for information he began, ‘The policeman downstairs said I should come here,’ and held out our one-year resident’s permits to mollify them.

‘What do you want?’ asked the woman, stubbing out her cigarette and taking a last gulp of coffee.

‘I want to settle here, to apply for permanent residency.’

She said nothing but took the proffered permits and walked into an adjoining room from which came the clatter of a typewriter. Paul stood by the paper-strewn desk, ashen dust powdering rubber-stamped documents, the aroma of coffee filling the airless room where even the plants hung yellowed and limp.

‘Fill these in,’ the woman said, then resumed her seat and lit another cigarette. Having been offered neither a pen nor a chair Paul sat down at a neighbouring desk and helped himself.

‘Come back on Friday,’ said the woman, giving no indication of what would then ensue, while Paul, all-too-familiar with the unspoken rules of the game, merely thanked her and left, eliciting another baffled stare from the policeman on the door.

To our surprise the permits were indeed ready on the Friday and valid for fifteen years. We contacted István with the good news and awaited further instructions.

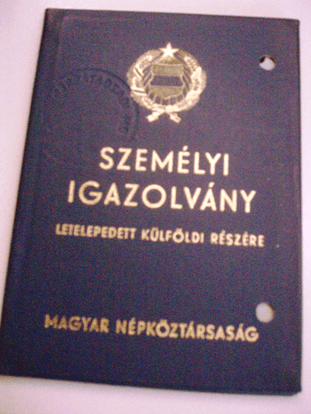

My I.D. for People’s Republic of Hungary

Meanwhile, I had been telephoned by a film producer requesting my help in revising the translation of a script for a production to star Michael York in a film about the war. He explained that he and the director were in a hotel in the city centre and asked me to work with them for two full days.

Both the pay and the work itself seemed attractive, and I accepted. It transpired that the two men were dissatisfied with the translation and wanted the somewhat stilted dialogue enlivened.

When I had finished on the second afternoon the director said, ‘We’ll be back in Budapest to shoot a couple of scenes from the film. If you’re available we could use you to go through the lines with the Hungarian actors – it’ll be in the second half of October.’ I accepted the offer with enthusiasm.

Click here for earlier extracts

Main photo: Metro line 1 prior to its renovation

LATEST NEWS IN community & culture