An Englishwoman's Life in Communist Hungary: Chapter 1, Part 4.

- 21 Oct 2022 11:36 AM

Now You See It, Now You Don’t and House of Cards have been included as part of the Open Society Archive dedicated to this period in the CEU. You can read a serialisation of them here on Xpatloop. You can also buy the dual-volume book on Kindle as well as in Stanfords London.

Chapter one: Beginnings and Belongings: Vántus Károly utca

Part four - The Music Academy; move to Dózsa György út

Two weeks passed quickly and then I was back in Budapest. Paul told me that in my absence Éva had called to explain that they had at last completed the flat swap, so that they, and therefore we, would be moving on the first of November. She had promised to take us to see the flat when I returned from Baja.

The Music Academy had organised our residence permits for a year, so it would no longer be necessary to pay our monthly visit to the police station. The academy had received word from the Hungarian removal company, Masped, that our container of goods had arrived from England, but we decided to delay delivery until we moved to the new flat.

October arrived, and with it, the autumn; the first cool mornings and a hint that the ‘old women's summer’ (Indian summer) was coming to an end. The children in the building opposite, not a school but a nursery, no longer had their midday nap on the balcony. When I had first seen the row of beds I thought it was a hospital.

Children from the age of six months can be left in nurseries all day, leaving their mothers free to work. However, the majority of mothers leaving children under the age of three did so because the family could not have survived without the woman's earnings, not because she was eager to continue working.

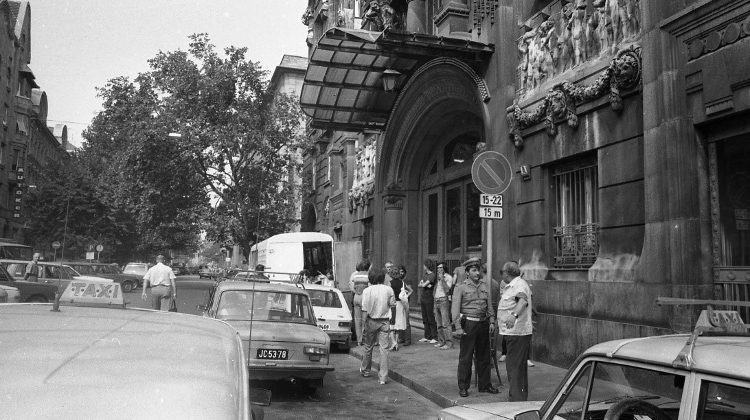

Paul had started his first term teaching Musicology and English at the Liszt Academy, an impressive turn-of-the-century building which stands four storeys high on the corner of Liszt Ferenc tér (Franz Liszt tér) and houses one of the city's main concert halls.

As you enter and walk into an airy, vaulted foyer with a floor of red marble, you may hear a rehearsal of Verdi's Requiem by a visiting orchestra, or an internationally-famous musician practising before the evening concert. It is usually possible to go in to the hall and listen at the back.

Past the snack bar and ticket office, any one of three staircases, again of red marble, will take you to the upper floors where the teaching and practice rooms are, rooms where Bartók, Kodály and a host of famous instrumentalists once taught.

By now I was at Lingua most days, teaching various groups of adults and children from the age of four. Things were slowly beginning to sort themselves out there, though with just four of us teaching, there were times when one of us had to cover another's lessons and this could result in long hours and heavy workloads.

As well as Miklós, János and myself, there was Ancsa, who also taught at the Economics University. If she was busy and one of the others was in the country, I occasionally had days of teaching from seven-thirty in the morning till nine in the evening with only a few short breaks.

It was the policy of the school for everything to be ‘English’, with tea in the breaks instead of coffee, with milk of course, and there was a very informal, friendly atmosphere.

After evening lessons, it became the custom for teachers and students to visit a nearby wine cellar, patronised by local working men, where we sat at heavy wooden tables in the semi-darkness under cart wheels transformed into 'chandeliers' drinking dry red wine and eating hunks of bread with raw onions. It was not unusual for the students to join in the singing which inevitably began as the evening wore on.

The Híd restaurant & wine cellar opposite Lingua Courtesy Fortepan/ Sándor Bojár

Something which had struck us on even our first visit to Hungary was that the espresso cafés and eating places, which seemed to constitute every third or fourth shop, were always full of people, even in the middle of the day.

‘But how is it that they are not working?’ I asked, a reasonable question in a country where unemployment was not only unknown, but illegal. The answer was always a shrug of the shoulders.

The other fact we found difficult to understand was how people could afford to spend their days drinking and eating out when they earned relatively little. But it became clear when we started work: though the average monthly wage was only three or four thousand forints, the daily expenses of food, gas, electricity, and the rental of a state flat were incredibly low.

A month's season ticket for unlimited travel on the very efficient public transport system with a choice of bus, trolley, tram, or underground, was just one hundred and ten forints. The rent of an average two-room flat was some two hundred forints a month, and food was heavily subsidised. Gas and electricity charges were nominal, while a cinema, theatre or even an opera house ticket could be had for ten forints.

On the other hand, the price of a car, television set or washing machine, not to mention a flat (about a million forints for a private one, half a million for a state flat) was totally out of reach for the majority. Thus, the whole ethic of saving money was alien; money was for spending.

Majus 1 (Atrium) cinema Courtesy Fortepan/ UVATERV

To this had to be added one of the fundamental differences between working in Hungary and England: a Hungarian's salary is not his total income. Everyone had their second job. For a teacher this might be giving private lessons, for a craftsman it meant extra private work at a higher rate of pay than his official job, either in flats or for one of the burgeoning small private firms.

Official working hours were broadly from seven or eight in the morning till four or five in the afternoon. It is also true that many clocked in (or maybe did not) at their main job, then went out to do private work. This was particularly notorious in the building trade, where workmen would leave the site of a state block of flats to work on a private site, often ‘redirecting’ (as it came to be known) state building materials for the private job.

The succeeding days passed quickly in a whirl of teaching, shopping, and packing ready for the move. We had been to see the new flat on Dózsa György út, a broad avenue with Heroes’ Square and the City Park within a few minutes’ walking distance. It lay on the Pest side of the river on the first floor of an old building and overlooked a large courtyard full of plants and flowers.

There were two large rooms with twelve-foot high ceilings, a long kitchen, bathroom and toilet. But there were some disadvantages: there was no phone, and in our Buda flat we had got used to this luxury, and the flat was dark, a characteristic of courtyard flats. Even in the daytime it was necessary to have lights on. Nevertheless, we looked forward to moving somewhere larger and to having all our belongings delivered.

The move was completed quickly and easily. The large wall units were carried resting on a long belt wrapped around the shoulders of the two removal men. The elderly lady doing the swap with the Dózsa György flat was of course moving on the same morning, but by the time we arrived she and her belongings had already gone.

Dózsa György út, our street corner Courtesy Fortepan/ FŐFOTÓ

Éva's aunt and uncle lived on the ground floor below us, and her uncle had taken it upon himself to look after the courtyard garden. He was proud to show us two certificates he had been awarded by the Budapest City Council in recognition of his work.

Our car had to stand in the road outside the main entrance to the building. This was the first time we had used it since arriving almost three months before, and we decided it was more of a problem than an asset, what with the parking difficulties and the steady disappearance of its bits and pieces. We decided to lend it to Miklós's brother, Dani, who lived in a small town outside Debrecen, since he would make good use of it and knew enough about cars to maintain it.

Éva supervised everything. Then as evening fell, she left us in candlelight - the electricity had gone wrong that very day. I watched from the uncurtained window as she waved and trotted down the worn marble steps into the courtyard, out of the huge wooden gate and into the dimly-lit street.

Main photo: Music Academy, Liszt Ferenc tér - Courtesy Fortepan/ Rendőrség

LATEST NEWS IN community & culture