An Englishwoman's Life in Communist Hungary': Book 2, Chapter 3.

- 27 Dec 2023 11:01 AM

Now You See It, Now You Don’t and House of Cards have been included as part of the Open Society Archive dedicated to this period in the CEU. You can read a serialisation of them here on Xpatloop. You can also buy the dual-volume book on Kindle as well as in Stanfords London.

Book Two, Chapter Three: Neighbours

Part Two – First elections; further deliberations

Spring had arrived. Hungarians traditionally counted it from March 15th, the anniversary of their uprising against the Austrians in 1848.

This had always been a holiday for students and schoolchildren, but the government had shied away from making it a national holiday. Now the red, white and green of the Hungarian tricolour fluttered proudly alone from buildings and bridges, the red communist banner absent for the first time.

My first students in 1982 from the Karl Marx University of Economics had bravely removed these red flags at night – then an illegal act with severe repercussions.

On March 25th the first free elections in forty-three years were held. We did not have the right to vote, but we watched as people – most for the first time in their lives – walked to the local primary school to cast their ballots. The election was won by the Hungarian Democratic Forum, a centre-right party.

Germany’s Chancellor Kohl shakes hands with Hungary’s first elected prime Minister, József Antall

We arranged to visit Virginia. We rarely saw her in Budapest, as she was nervous of driving in the city, especially with Flora distracting her from the back seat. As our car slid through the mud of the garden gate Virginia emerged, dishevelled, from the total wilderness of wet weeds, a bucket in each hand.

‘What are you doing?’ I asked as I opened my door.

‘I’m collecting snails,’ she said, thrusting the two muddy buckets towards me, where the huge slimy creatures were sliding over one another. ‘They put up signs around the town a week or two ago – they’re paid for by the kilo. I think they’re for export to France. I’ve already taken in about five kilos.’

We walked towards the house, stopping to put a plank across the tops of the buckets, then leaving them on the porch of the huge verandah. Paul followed carrying Hannah, still asleep, while John insisted on removing the plank from the buckets and watching the snails. Paul stayed on the verandah while Virginia and I went in to make some tea.

‘So how are you?’ I asked, as we stood by the cast-iron stove, watching the kettle boil.

‘I’m tired,’ she said. ‘Flora’s still not sleeping – I’d leave her to cry a couple of nights and see if she learns to sleep through, but József still refuses. Mind you,’ she added, ‘he sees to her too, and he still manages to get up at four thirty. He seems to have so much energy, he can’t understand that I need to have a nap in the afternoons.’

‘She’ll grow out of it,’ I reassured her. ‘How are the plans going for the new vicarage?’

‘Come and see.’ Virginia led me out of the kitchen to the congregation room.

‘Look.’ She pointed out of the window to where the organist’s house had stood. ‘They pulled it down last week. They’ll be starting the new foundations next.’

‘That’s great! When will it be finished?’

‘That all depends. Most of the workmen are church members who will give their time for nothing, but that also means they rarely come.’

‘And what about the plans? Can you decide on the layout?’

Virginia stared vacantly out across the messy tangle of weeds and broken bricks outside. ‘Yes, theoretically....’ I waited. ‘But József says it’s his decision and nothing to do with me.’

I did not know what to say. Though I had had vague, uneasy feelings of tension between them, Virginia had never voiced any criticism of József before today, and her mood was now resigned and sombre.

‘The kettle’s boiling,’ she said at last, turning from the window. I followed her, though not before noticing the deep crack in the wall beneath the window ledge we had examined on our last visit: it had widened, and small pieces of grey plaster had crumbled to the floor below.

We drank our tea on the terrace while John tried to count the snails, setting them down in rows. They soon slid forth leaving silver trails criss-crossing the ground, one or two slipping out of reach among the cobwebbed ivy jungle. Dusk fell and the air grew chill. The snails were recaptured and secured, both tea and supper things were returned to the kitchen and belongings collected up.

‘I’ll send you a telegram when we can come again,’ I said.

‘Do come soon,’ Virginia said with a tinge of pleading in her voice, which I wished I had only imagined.

*

As spring warmed to summer discussions of whether or not we should stay in Hungary became daily. We could not stay at Róbert Károly körút, already our sixth rented flat, thus a move of some kind was inevitable. Yet after eight years it seemed we could no longer delay the decision as to where we were to make our permanent home.

England offered a return to everything familiar, family and old friends, a language and a culture which required neither effort nor thought; security in the knowledge of how things were done, and the all-pervading, logical simplicity of everyday life.

How tempting these aspects of English life had proved to those Hungarians who had left over the years to begin new lives in England; how often we had been thwarted in our attempts to justify abandoning them and coming to Hungary!

Yet I could not escape a feeling of surrender, of failure even, at the thought of returning – a denial of all I had been taught and all I had learnt about myself when faced with the many challenges of the previous years; a rejection of our many friends, and ultimately the severing of all my ties with my adoptive city.

This could no more be an objective decision, a question of drawing up lists of advantages and disadvantages, than falling in love.

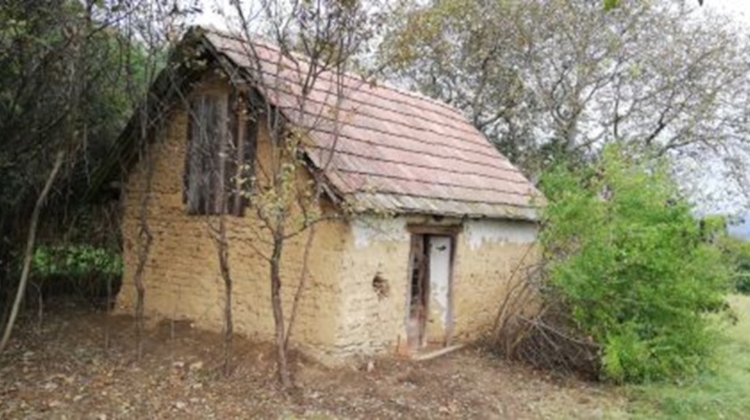

The illogicality of seeing beauty in the old and ugly, the disused and crumbling, the worn and outmoded, was undeniable. My resentment towards the new and the painted, the neat and the tidy, bore witness to the process of imprinting I had undergone in eight years of living in Hungary: love was indeed blind, and also inescapable.

However, if we were to stay it would be permanent. Our savings in England, once used to purchase a flat in Budapest, could not be exchanged again for hard currency.

The convertibility of the Forint seemed as distant as it had always been: if we bought an apartment in Hungary we would firmly bolt the door to leaving.

We also wondered about the realities of trying to bring up the children bilingually, and decided to ask Caroline to visit us and discuss it. Caroline had come to Budapest in the late sixties to visit her penfriend István, whom she had married soon afterwards.

They had three sons and lived just outside the city. Caroline was a fount of information on every aspect of Hungarian life, and a source of wisdom and impartial advice. She did not seem surprised at our decision to stay and confidently predicted that John and Hannah would only benefit from learning two languages.

‘But won’t they become schizophrenic?’ asked Paul.

Caroline chuckled. ‘You might,’ she said, ‘but they’ll be fine.’

We asked about how she and István had dealt with the boys’ double identities, and their competence in English.

‘So, it all worked out for you, then?’ I said.

Caroline looked serious and her face fell slightly. ‘Well, yes, apart from the fact that István and I are separating. But that shouldn’t affect your decision to stay,’ she added lightly, obviously unprepared as yet to talk about the reasons for the end to her long marriage.

Click here for earlier extracts

Main photo: 1990 Election posters

LATEST NEWS IN community & culture