Special Report: Current Lockdown May Last Way Longer Than Two Weeks In Hungary

- 11 Mar 2021 11:40 AM

Some countries ravaged by the UK coronavirus variant have been in tight lockdown for two months now. But there's hope.

The new restrictions have been implemented on top of existing ones, the weather is getting better (warmer), the vaccination campaign is in progress. These might imply that the Hungarian economy will be benched for a shorter period, but warnings by various experts do not bode well.

Two weeks, four weeks… A forlorn outlook

PM Orbán made contradictory statements / estimates last Friday in relation to the new lockdown measures and the possible dates of re-opening.

First, he said that: "on the week starting with 15 March we'll work out how we can gradually re-open after Easter", that is 4-5 April, i.e. a month from the 5 March interview.

Then at the end of the interview he said: "we are in the final straight in the war against the virus. We could start a gradual re-opening in two weeks."

We still don’t know whether he thinks re-opening could be possible in two weeks or four weeks, and it also needs to be clarified what the difference is in the official communication between the easing of restrictions and re-opening.

In any case, our findings show that where the third wave of pandemic kicked in with such fervour in Europe, they were in no position to decide on a meaningful easing of restrictions even after a month let alone two weeks.

To be able to come up with the most accurate estimates possible we have looked at two factors:

-

1. When did the pandemic start to peter off after restrictions had been implemented on 11 November 2020?

-

2. How long did European countries devastated by the UK variant (and asked for international help, such as Portugal in January, and Slovakia, and the Czech Republic in February) hold on to lockdown measures?

These experiences do not show what will only what could happen in Hungary, as there are various other factors, rather uncertain ones, at play here, including the content of the specific measures, the population’s discipline at adhering to the regulations, the situation in hospitals, the success or failure of the vaccination campaign, weather conditions, etc.

How did the autumn wave of the pandemic go?

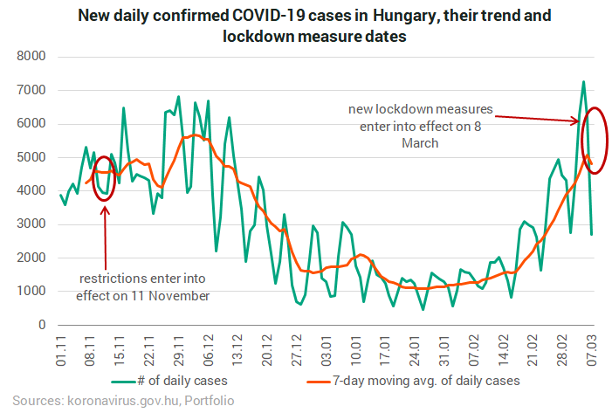

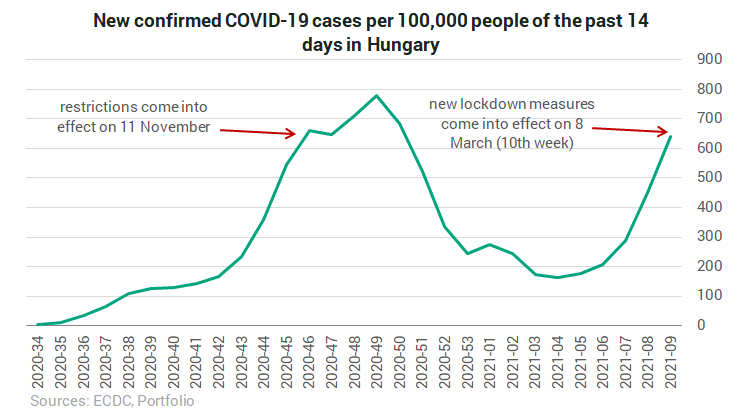

It took the restrictions implemented on 11 November largely 8 to 10 days to start flattening the curve of new daily COVID-19 cases and their 7-day moving average. In late November, early December, however, the results of 100,000 to 200,000 tests came in and upset the time series, causing a temporary fluke in daily figures and the trend, as well.

As a consequence, the moving average started to show a descending trend only after about a month. This suggests that the new lockdown measures put in place for two weeks could easily be extended until at least Easter.

There’s obviously no linear linkage between the epidemiological findings in a sense that the November restrictions and the new lockdown measures, as the latter were implemented already amidst restrictions, hence it could achieve greater results at cutting personal contacts, for instance.

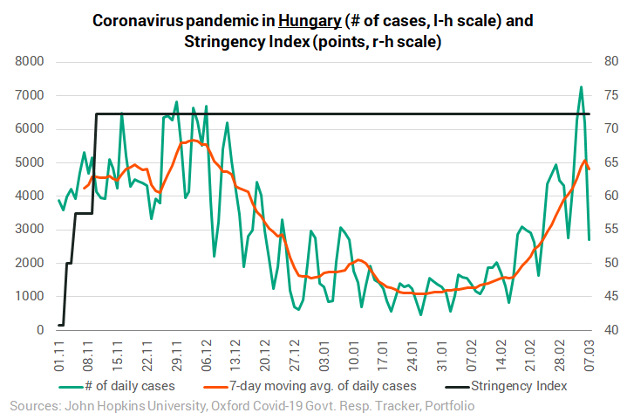

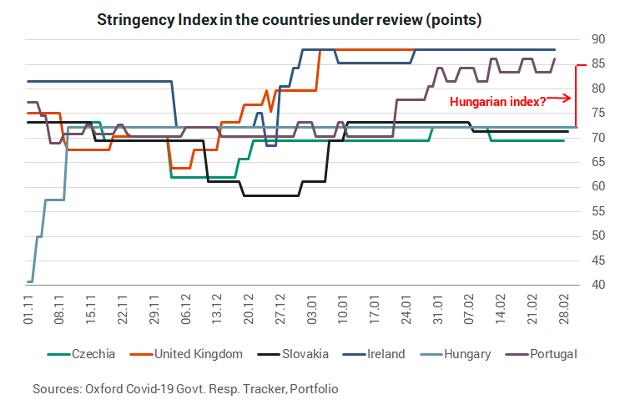

This is shown on a 1 to 100 scale of the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker, or more precisely its Stringency Index. The Hungarian score has not been updated yet with the new lockdown measures, but we estimate the country could now be around 85 points following its stagnation at 72.2.

The correlation is not linear also because of the faster spread of new variants, while the new lockdown measures came into effect at practically the same infection numbers as last November (640-650 per 100,000 inhabitants for the last two weeks).

What is indeed the same is that the government acted too late both last November and this March. And now hospitals are under much greater pressure than last autumn.

So, let’s see some foreign examples to assess how long the strict lockdown measures could stay with us.

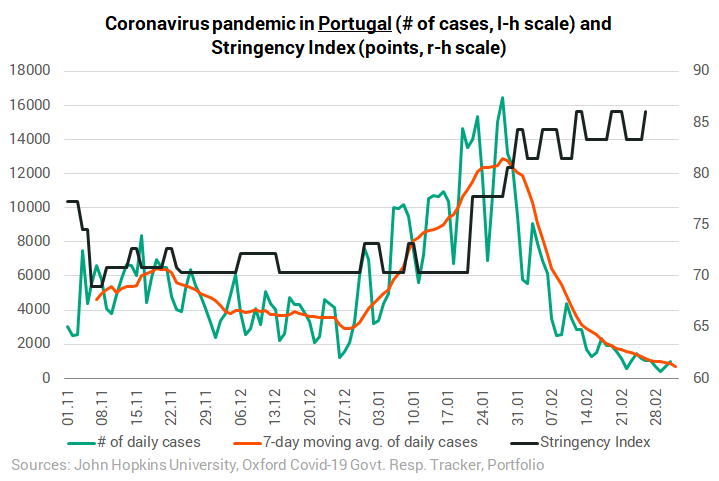

In Portugal, a country with extremely late reactions by the government that may serve as a deterrent for other nations, restrictions started in the second half of January.

It had several stages but no marked easing is possible despite a drastic drop in the number of new daily cases and the 7-day moving average which was under 1,000 last week, down massively from a peak around 13,000. Due to belated action the country has been living in lockdown measures for almost two months now.

Czech Republic is still in no position to ease restrictions implemented in mid-December 2020. Although the upward trend was broken in January, the spread of coronavirus gathered pace again in February. This suggests that the lockdown measures are still not tight enough (Stringency Index under 70 points), and further restrictions could be necessary.

The Czechs have been living in lockdown conditions for three months now and they're definitely not thinking of easing restrictions.

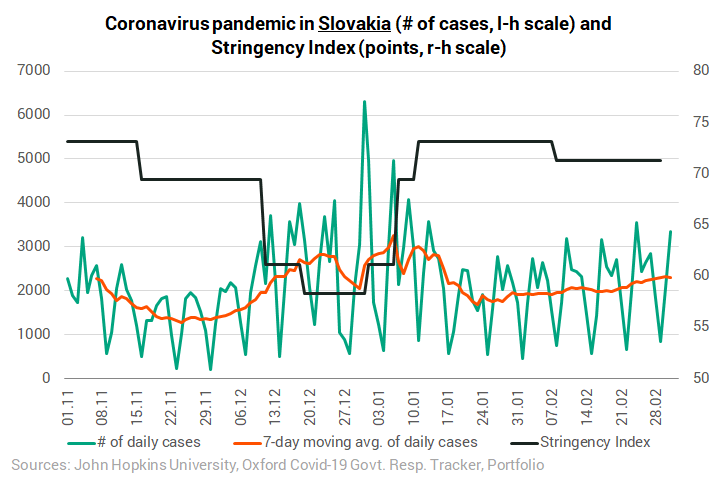

Slovakia was unable to considerably ease restrictions implemented after Christmas, and its COVID-19 statistics are not promising. These suggest measures could/should be tightened further.

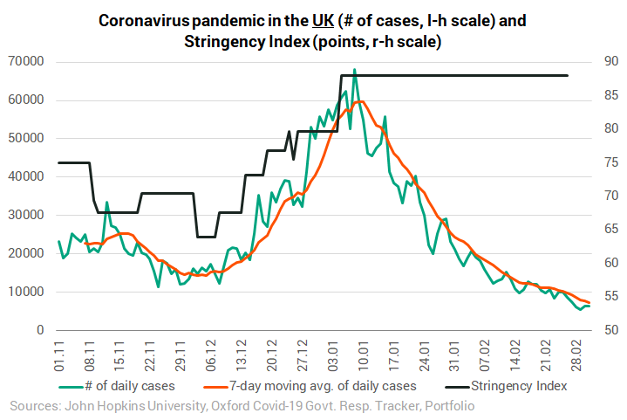

The United Kingdom, the ‘homeland’ of the UK or Kent variant implemented new restrictions in early December and then in early January. The first step towards a normal life after an almost full two-month lockdown there was taken on 8 March when schools were re-opened after two months of distance teaching. Owing to stringent restrictions the 7-day moving average is back under 10,000 from a peak of over 60,000.

Note that the UK kept strict lockdown measures in place for over two months, while its vaccination rate has been going up nicely and by now more than one third of the population is inoculated against covid19.

Hungary’s Chief Medical Officer Cecília Müller admitted on Monday that the UK variant is now dominant in positive samples, warning that the health care system is under immense pressure. Up to date, only 10% of the population received their first COVID-19 jab and the 20-25% range could be reached in about a month.

This strongly suggests that the re-opening of the economy will not be / should not be on the agenda two weeks from now, and it might be a dangerous call to make even around Easter.

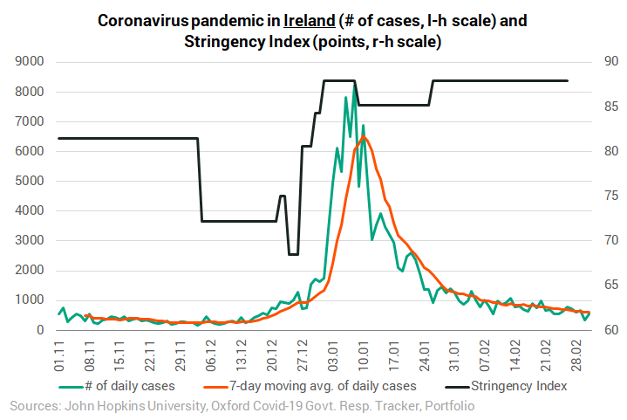

Ireland, where the Kent variant has also become dominant, is another example of lasting restrictions.

As you can see on the chart below, protective measures have not been eased permanently since their implementation after Christmas despite a significant improvement in coronavirus statistics.

The 7-day moving average of COVID-19 cases has been steadily south of 1,000 for weeks, down from the peak reached around 6,500. Meanwhile, only 7% of the population have been vaccinated against COVID-19 by now.

And now we need to address three key factors that could determine the duration of the lockdown measures in Hungary, but the impact of which on the pandemic cannot be estimated with precision.

These are:

1. the Stringency Index,

2. weather conditions,

3. the vaccination rate.

The Hungarian government’s anti-pandemic measures have already scored higher on the Stringency Index than those in Czechia or Slovakia, although such comparisons should be made with caution.

The fact that Hungary has just turned lockdown measures up a few notches is reassuring that the situation here will be better. However, it is a warning sign that the new measures will take Hungary’s score to around 85, and although the Brits and the Irish have been living in similarly stringent (or even tighter) lockdown for two months, the first easing measure has been introduced in the UK only now, while a much higher percentage of its population has been vaccinated against COVID-19.

What about the weather?

It’s spring, the temperature is going up by the day, the strength of UV radiation will rise, people would go out more often, their immune systems could grow stronger. While fair weather can have these positive effects, it can also relax people’s awareness and increase contact numbers, so it’s a double-edged sword.

With the help of Russian and Chinese vaccines, Hungary has a chance to inoculate a large percentage of the population within a relatively short period of time, and take the lead in the EU in terms of the vaccination rate (currently Malta is on top) within a couple of weeks. The more people are immune to coronavirus (via inoculation or infection), the shorter the duration of the lockdown could be.

Orbán said last Friday that some experts think the new lockdown measures could break the third wave after 10 to 12 days. Others estimate 14 days, and some think re-opening after 14 days should be done very cautiously in order to avoid a fourth wave, he added.

This suggests that the PM is aware that premature re-opening could lead to an even more rampant pandemic. Hungarian hospitals are under extreme pressure already, and coronavirus started to spread more rapidly in Slovakia and Czechia even though restrictions, albeit possibly not sufficiently rigorous ones at that, were kept in place.

Overall, we do not believe a significant easing of lockdown measures will / should be on the agenda two weeks from now, and easing right after Easter could also be risky. Those that have recovered from coronavirus or have been vaccinated could be exempted from certain restriction measures, but as they can still contract and pass on the virus, even this step should be considered very carefully.

Béla Merkely, rector of the Semmelweis Medical University in Budapest, estimated last week that the pandemic situation will be a lot better by mid-May, and a gradual easing of restrictions could be started then.

Other experts have also warned about the drastic situation in health care and against a pre-mature re-opening of the economy.

Source: Portfolio.hu

Republished for readers of XpatLoop.com with permission.

This is one of many daily articles in English on Portfolio.hu

Portfolio English Edition's premium content is available only for subscribers

Subscribe to learn about the hottest news of the day, along with immediate follow-up analyses and 1000's of exclusive articles with full access to the premium content.

Follow this link to apply for a free two week trial Portfolio.hu subscription in English.

Cover photo: MTI/ Noémi Bruzák.

A policeman and a soldier on patrol in Budapest Jászai Mari square on 16 November 2020.

LATEST NEWS IN current affairs