An Englishwoman's Life in Communist Hungary: Chapter 2, Part 5.

- 22 Nov 2022 1:52 PM

Now You See It, Now You Don’t and House of Cards have been included as part of the Open Society Archive dedicated to this period in the CEU. You can read a serialisation of them here on Xpatloop. You can also buy the dual-volume book on Kindle as well as in Stanfords London.

Chapter Two: Snow and Settling: Dózsa György út

Part 5 - Return journey and arrest

Christmas came and went, the traditional mixture of too much food and too little exercise. It was a pleasure to go shopping where you were sure of finding what you wanted, only the choice was intimidating. And yet, surprisingly, we felt keen to return to Budapest when the time came.

Endre had rung to ask me if I could find a doctor willing to issue a medical certificate for his daughter Flóra, stating that she had been too ill in Germany that summer to have travelled back to Hungary. This would provide them with a reason to satisfy the police as to why they had overstayed their visas.

Our suitcases were considerably heavier on our return journey from Braunschweig. There was only one train from East-Berlin to Budapest leaving at ten-thirty at night, and the connections were bad – either we would arrive at nine-thirty at Friedrichstrasse, leaving only an hour to cross the border and get to the Ostbahnhof, or we would arrive at six o’clock, giving us a good four hours. We decided that the possibility of missing the Budapest train and having to wait twenty-four hours for the next was not worth the risk.

At two o’clock we drew out of Braunschweig station and arrived at the last western station, Berlin Zoo, at almost six o’clock. It was dark as the crowds of West Berliners got off the train and headed for the bright neon lights of their city.

Some looked at us curiously, one even called through the compartment door, ‘This is the last stop in West Berlin!’ I thanked him and remained seated. Two elderly ladies sitting opposite, ignoring us, began to chat.

‘I'm always so nervous going back, I'll have to go to the loo,’ with which she left the compartment.

East Germans cross to West Berlin Courtesy Wikimedia

On crossing the Berlin wall at night, I concluded that the entire East German national grid must be working overtime, lighting up the area like Blackpool illuminations. Guards with dogs patrolled the barbed wire perimeter while others with binoculars watched the train from their look-out towers.

There were fewer people crossing over at Friedrichstrasse than there had been on our westward journey. We stood in line waiting and watched the pathetic scene as a guard ordered an elderly man to open his brown, battered suitcase.

Moving some of the clothes to one side, he withdrew an orange and began to examine it minutely, holding it up to the light. The man waited nervously, fidgeting, passport in hand. Then the guard replaced the orange and motioned to its owner that he was free to close his case and leave.

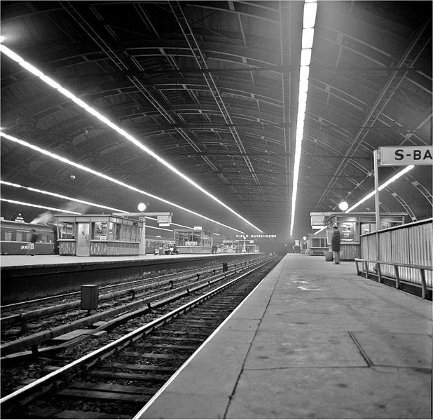

As western nationals in transit we were of no particular interest, though we were asked about the contents of our suitcases. Back through the 'horse boxes' and up the steps to the S-bahn. Arriving at the Ostbahnhof we found the small waiting room completely full.

We had some spare East German Marks, weightless as milk bottle tops, and decided to eat in the station restaurant to keep warm and pass the time. It was a cheerless place, its dullness reflected in the tasteless food. Nevertheless, it was busy, and it was with great joy that we recognised someone speaking Hungarian at a nearby table from which much laughter emanated.

The train left punctually at ten-thirty. It had been bitterly cold on the platform and everyone had waited in the tunnel below until the last possible moment. We chatted, finally going to bed in our sleeping compartment at about midnight. We had hardly slept at all when the lights were abruptly snapped on about half an hour later. ‘Passports, visas!’ commanded a voice.

We struggled towards consciousness and handed over the various documents. These duly stamped, the East German guard left, to be followed some minutes later by his Czech counterpart.

Speaking in German he asked me, ‘Where is your Czech visa?’

‘There,’ I said, pointing to it.

‘This is not valid, you have already crossed the border twice,’ he continued.

‘I don't understand,' I said. ‘We live in Budapest and we've been to West Germany and now we're going home. This is what they gave me at the Czech embassy in Budapest.’

‘It's not valid,’ he repeated.

‘Well, can't you sell us a new one?’ I asked. ‘We've got photos.’

‘Maybe when we reach the border in about fifteen minutes,’ he replied. ‘You had better get dressed.’

So saying, he left the compartment, taking our papers with him.

We dressed and waited. The train soon came to a halt and doors banged as guards disembarked and others got on. Our door swung open.

‘You will have to leave the train,’ said the guard.

‘But why?’ I protested. ‘Can't you sell us a visa?’

‘That is not possible, not until the morning, please bring your belongings.’

We hauled our luggage off the racks and followed him off the train. It was pitch black apart from the lights from the train and bitterly cold with thick snow underfoot. We were led to a small building on the platform and into a large room containing a long, wooden table and chairs.

Behind us, the barred gate was locked. We sat down. In the corner of the room a man was asleep, while opposite sat what looked like three Pakistanis. The clock on the wall showed almost one o'clock. After some minutes we heard the sound of a key being turned and a guard came in.

‘We can let you have visas at about five o’clock when the next shift arrives,’ he said. Apparently, there was another train bound for Budapest some time that morning. I translated for Paul, whereupon the three men opposite addressed me.

‘We can get visas, five o'clock?’

‘Yes,’ I replied. ‘Where are you going?’

‘Islamabad,’ came the reply. ‘We had luggage stolen in Amsterdam,’ they continued, ‘but have money and papers.’

I nodded.

We lay down along the row of wooden seats, but with the bright lights, the chattering of our companions and noises of the guards in an adjoining room, sleep was impossible. Eventually, at four-thirty the guard came in again.

‘We can't let you have the visas here,’ he told us. ‘You must go back to West Berlin.’

‘West Berlin?’ Paul echoed.

‘Here's the address,’ said the guard, handing me a piece of paper.

Protests were in vain, we were to be put on the train coming from Budapest at five o’clock. I translated for the Pakistanis.

‘Is big trouble?’ they asked me.

‘Is very big trouble,’ I replied.

‘East Berlin, West Berlin same?’ they enquired.

I shook my head.

At five o'clock we were all escorted to the waiting train, including the man who had slept soundly throughout the night's disturbances. The Pakistanis tagged along behind, seemingly unconcerned about what to them was a small detour in a much longer journey. Within minutes the East German guard burst into our compartment. ‘Visas! Passports!’ he shouted.

‘We haven't got visas,’ I said wearily, imagining a situation where we could spend an indefinite amount of time sitting on this bleak border. I explained the situation. The guard leapt to attention, ‘We in the German Democratic Republic will give you a visa at any time,’ he said, thrusting the familiar forms at me.

At eight o’clock we were back at the Ostbahnhof for the second time in twelve hours. Having decided to leave our cases in the left-luggage, we bought our S-bahn tickets, and with a feeling of being back in my school-teacher days in England I gave each of the Pakistanis theirs, ‘One for you, one for you…this way,’ I said as they followed in a single file.

Once more through the terrapin building at Friedrichstrasse, trying to avoid looking at my washed out face and dark-circled eyes in the hard fluorescent lights. Then out into the unknown, the West Berlin tube network, with only the address on the paper we had been given.

Border crossing in East Germany

No-one I approached had heard of the street, and looking at my watch I saw it was already nine-thirty, and I realised that few consular departments in embassies would stay open much beyond eleven or maybe noon. Time passed, and then eventually an old man peered at the address, thought and said, ‘Ah yes, I know it, but it's not here, it's over in East Berlin.’ We could not believe it, but he was certain.

‘What do we do now?’ I asked Paul. ‘If we don't get to the Czech embassy before they close we'll have to spend the night here and we haven't enough money left.’

‘Let's find a phone box and look in the telephone directory in case there's also a Czech embassy here in West Berlin,’ he replied. We trooped up onto the street, and not far away was a phone box, but no Czech embassy was listed. ‘What now?’ I asked. ‘Let's try the British Embassy. They might know,’ Paul said.

I relayed the situation to the Pakistanis waiting outside.

‘We have friend, West Berlin,’ they said after some discussion. ‘We go there,’ and then with smiles and handshakes they left.

The British Consulate informed us that there was a Czech mission in West Berlin and dictated the address. They also said that the consular department was likely to be open only until eleven o’clock. It was already nearly half past ten. We hailed the first passing taxi deciding that our visas were more important than food, and managed to arrive in time to be the last people issued with Czech visas that morning.

With the relief of knowing we could return to Budapest on that night's train, came a sudden and overpowering sense of sleepiness and fatigue. We had not slept since getting up the previous morning in Braunschweig, some twenty-eight hours ago, and there would be no real opportunity to sleep for almost another twelve hours.

We decided to remain in West Berlin until evening, though we had no idea what to do with no money and in sub-zero temperatures. We walked the crowded shopping streets, unwashed and unkempt, too tired to talk or even care which direction we were going.

Then ahead of us we saw a large, modern church and decided to go inside and have a look. It was warm and dark inside, the Christmas tree still in place, and a few small groups of people admiring the nativity scene and candles. This, then, was the answer. We found two seats behind a pillar, and settling ourselves down, managed to doze on and off for several hours.

Early in the evening we made our way to Friedrichstrasse.

‘Where is your luggage?’ asked the customs officer.

‘At the Ostbahnhof,’ I replied wearily.

‘I must see it,’ came the response.

‘You did – yesterday.’

‘I must see your luggage,’ he repeated, pointlessly.

I began to explain, slowly, waiting for him to realise that our luggage could only have got to the Ostbahnhof through this same border, when he cut me short and told us to go. My initial feelings of intimidation when we had first crossed through Berlin two weeks earlier were fast turning to impatience and disdain.

Ostbahnhof, East Berlin Courtesy Wikimedia

Once at the Ostbahnhof, we managed to find two seats in the waiting room and tried not to sleep for fear of losing our luggage. Eventually we boarded the train, now with no booked sleeping compartment or seats – we had been extremely lucky that our tickets had not been punched on our previous day's abortive journey.

However, the train was almost empty, and the seats pulled out from the walls, so that by pulling out all six we contrived a very comfortable bed. We crossed the Czech-Hungarian border early in the afternoon and as I stared out of the widow I realised that Miklós and János would probably have been to Keleti station the previous day to meet us, and that I was supposed to be teaching that very evening. It was too late to wander the streets in search of a phone that worked.

We took a taxi the short distance to our flat and fell straight into bed.

Main photo: The Berlin Wall Courtesy Fortepan/Korbuly family

LATEST NEWS IN community & culture