'An Englishwoman's Life in Communist Hungary': Chapter 3, Part 10.

- 7 Feb 2023 12:18 PM

Now You See It, Now You Don’t and House of Cards have been included as part of the Open Society Archive dedicated to this period in the CEU. You can read a serialisation of them here on Xpatloop. You can also buy the dual-volume book on Kindle as well as in Stanfords London.

Chapter three: Market and May Day: Garay tér

Part 10 – Aggtelek caves; an American in Dabas

The following morning, after a breakfast of cheese, eggs, toast and coffee - we declined the offer of an early-morning pálinka - we left Feri's Trabant and set off in his father's Lada for the caves at Aggtelek.

The main street through the village was lined with people going to church, mostly elderly men in their best black Sunday boots and hats, top buttons of their shirts tightly fastened but without ties, and women in lace-up boots, dark coats and headscarves.

The bells resounded down every street. There was a cool dampness in the air, a first hint of autumn that had been totally absent in Budapest, while a few wisps of mist hung over the fields.

The road wound through the forested hills, giving occasional glimpses of fields and valleys far below.

There was hardly any traffic, just the occasional horse and cart or cyclist in the middle of the road. When we arrived at Aggtelek we were surprised to find only two other cars in the large car park under the trees.

We all shivered as we got out of the car, but knowing it would be still colder underground, resisted the urge to put on our sweaters.

Ahead of us lay steep cliffs, and to the left a small museum and ticket office with one or two people in anoraks and rucksacks hanging about outside. The ground was wet, and the trees dripped from the mist.

A sign on the window of the ticket office announced that the next guided walk around the caves, which would last one hour, would leave in forty-five minutes, so we went into the museum. There was an interesting display of rock samples, the history of the caves, and many photographs.

Unfortunately, as in so many museums and places visited by tourists, all the captions were in Hungarian.

We were the only people there though, and so the curator was only too pleased to supply us with additional information.

A shout from outside indicated that the guide was ready to leave, so we bought our tickets and joined the half-dozen other people outside. Unfortunately, the end of August marked the end of the official tourist season at Aggtelek and the longer tours underground, which included a boat trip on an underground river in the caves, were no longer being undertaken.

Aggtelek is a vast complex of caves which crosses the Hungarian-Czechoslovak border underground. All the caves were well lit with beautiful stalactites and stalagmites in a variety of colours, and many had been given names inspired by their shapes.

A number of small underground streams had wooden bridges, and in other places duckboards had been placed over the wettest areas.

Aggtelek caves Courtesy Wikimedia

Leading from every cave were tunnels, some of them unlit, and we were warned more than once to keep together if we hoped to see daylight again. The most impressive cave was of immense proportions and was used for concerts. Rows of seats had been arranged and we sat while a tape was played through large speakers, the acoustics were perfect.

Our walk ended and we emerged, now into sunshine and warmth, the mist having cleared. It was almost midday and everyone was hungry. On the far side of the car park was a caravan we had not noticed when we had arrived, and it appeared to be selling food.

It was selling pancakes, and a choice of fillings was printed on a list on the small window: walnut, poppyseed, cinnamon, curd cheese or cocoa. We bought two of each piled on to paper plates, and taking also some serviettes and four glasses of strong, hot, black coffee we went and sat on a bench nearby to savour this unexpected snack.

Feri suggested that since we had not been there before, it might be interesting to see Szilvásvárad - the place where Prince Philip sometimes came to ride and take part in coach-and-four events. So, after yet a few more pancakes, we set off.

The road was deserted and for the most part overhanging trees formed a green tunnel along the narrow snaking lanes. Szilvásvárad itself is situated in a valley with a few picturesque houses, sloping meadows with grazing horses, and a grassy racetrack, while on every side rose the steep wooded hills through which we had driven.

We set off again, deciding to return by a different route, aiming to be home for a late lunch and return to Budapest in the early evening. According to the map we needed to take a minor road off to the right that would take us over the hill we were on, and back to the road to Bükk-Szent Erzsébet.

However, as we came to the turning we wanted, a roadworks sign and a trench right across the road blocked our path. There was nothing for it but to continue on the road we were on and hope that we could find another way home, although no other turning was shown on the map.

We were in luck. Some miles further along the road was a single-track lane leading off to the right, only there was a white barrier across it which we could not shift. But Feri spotted a small house almost hidden in the trees further up the track and walked towards it.

We waited. After a few minutes he came strolling back accompanied by an elderly man carrying a large bunch of keys and a book as thick as a telephone directory. He greeted us politely and explained that the road was in a nature reserve, not open to traffic, but if we would sign his book, declaring that we would drive at a maximum of twenty miles-per-hour, not pick any flora or interfere with the fauna, picnic, or in any way damage anything, he would allow us through.

Feri produced his driving licence and signed the book, and the man unlocked the barrier and waved us on.

We drove slowly, as birds flew shrieking up from the track, obviously unaccustomed to traffic. Weeds grew up in the middle of the lane, while bushes and trees brushed the sides of the car. Once a deer leaped into the undergrowth as we approached and rabbits scurried for their burrows.

Then, quite, unexpectedly, there would be a gap in the trees and we discovered just how high we were, seeing the steep rocks and the sparse grass and wild flowers in the crags, and the clouds floating past below us casting shadows across the valley.

This was a completely different landscape from the one we had left behind on the road below. It was wild, totally unpopulated, reminiscent perhaps of parts of Austria. It was a short road leading over the hill and down the other side, and where it rejoined the main road there was a No-Entry sign, and another barrier which was, however, not locked.

Driving back into Bükk-Szent Erzsébet, most people had already eaten and many were busy on the fields in the warm sun. Whole families were bent double, hoeing and weeding, the women in bright headscarves - colourful blobs on the brown landscape. Their bicycles were lying between the grass verge and the edge of the field together with bags containing food and drink.

Back at Feri's home, pálinka glasses stood ready on the table, though not for Feri who still had to drive, nor for his father who was soon leaving to work a night-shift. Lunch was soup, stuffed peppers, roast pork and finally coffee and cake.

Feri had a choir rehearsal in Budapest that evening, so we slowly gathered up our things and put them in the car. One final trip to the loo and we were ready to leave. At the last moment, Feri's mother appeared with small packets of food wrapped in silver foil, eggs, cakes and cold meat for Feri, so he should not starve before his next visit, and a bottle each of home-made pálinka and wine for us.

Feri's parents and sister stood at the gate waving and calling to us all to come again soon as we spluttered our way down to the main road, followed by an excitedly barking dog.

September was drawing to a close, my brother's visit was over, and Paul and I returned to our usual daily routine. The hot weather continued beyond when the clocks were put back and into October - a real Indian summer.

I soon received a postcard, in reply to my own, from Virginia in Dabas. She suggested we go and visit them the following weekend. Thus, we caught the train from the terminus of the metro line and on arrival at the small country station, scoured the crowd for someone carrying a carrier bag bearing the American flag.

We soon spotted Virginia, with her dark, curly hair and welcoming smile. She led us to a Trabant parked outside the station building, saying how much she had been looking forward to seeing us.

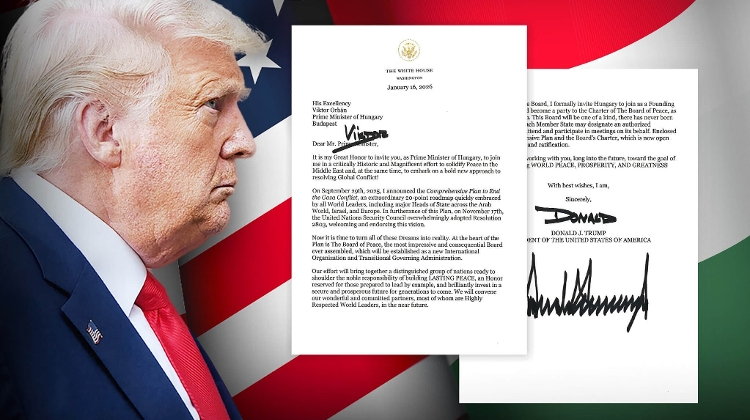

Dabas – Presbyterian church

We drove past the church where her husband, József, was the minister and on to the next corner where their house stood. It was an old, rambling vicarage with crumbling plaster walls, standing on a huge plot of land. Many trees surrounded it, and the veranda leading to the paint-flaked front door was covered with ivy and grapevines.

We followed Virginia into the large, but dark kitchen where she made tea which we carried out to the heavy, wooden table on the veranda, and seated in the shade of the ripening grapes and dusty ivy, she told us how she had come to Hungary.

‘And now I'm studying theology at the Lutheran College in Budapest,’ she concluded.

‘What, in Hungarian?’ I asked incredulously.

‘Yes. I take a cassette-recorder to tape the lectures, and then I write them down at home and look up all the things I can't understand.’

We could hardly find words to express our admiration.

‘Are you having Hungarian lessons?’ asked Paul.

‘Yes,’ she replied. ‘I went to Ócsa, the town between here and Budapest, and went to the local grammar school. I found the English teacher there, called Eta, and we made an agreement that I would give her practice and help with her English if she would teach me Hungarian. We meet once or twice a week.’

József arrived home, a tall, handsome man who welcomed us warmly in good English. Having repeated to him the gist of our story as to how we came to be in Hungary, Virginia and I walked down the steps from the terrace and to a small area of the garden where she was growing vegetables.

‘Where is the end of your plot of land?’ I asked, surveying the large area of grass and trees.

‘See where that ruined outbuilding is?’ she said, pointing to a small dilapidated, stone structure. ‘That marks the boundary. And guess what? Someone lives in there. He was an aristocrat, he had all his property confiscated and then he became an alcoholic. We don't really know his whole history, but he's homeless and lives in there - of course there's no heating or anything.’

Seeing my surprise she continued, ‘And see that huge house over there?’ I followed her gaze. ‘The local party secretary lives there, of course they won't even speak to us.’

We spent the remainder of the afternoon soaking up the last mellow rays of sun as they filtered through the vine leaves, exchanging tales of our Hungarian experiences, and when the shadows lengthened, we prepared to leave for the station.

As Virginia started the engine of the Trabant an elderly woman rode up on a black, squeaky bicycle and asked where she might find József. ‘People come and go all day long,’ Virginia observed. ‘Without a telephone everyone has to come personally whether they want to arrange a funeral, or they just need a key to the church.

If you're trying to work it can be really irritating, however kind and friendly the people here are,’ she said. We squeezed into the car and bumped off down the unmade road in a cloud of dust, agreeing to keep in touch and meet again soon in Budapest.

Dabas station

Click here for earlier extracts

Main photo: Aggtelek caves, entrance - Courtesy Fortepan

LATEST NEWS IN community & culture