'An Englishwoman's Life in Communist Hungary': Chapter 4, Part 6.

- 19 Apr 2023 7:10 AM

Now You See It, Now You Don’t and House of Cards have been included as part of the Open Society Archive dedicated to this period in the CEU. You can read a serialisation of them here on Xpatloop. You can also buy the dual-volume book on Kindle as well as in Stanfords London.

Chapter four: Courtyard and Characters

Part 6 – Recycling communist style; Chernobyl

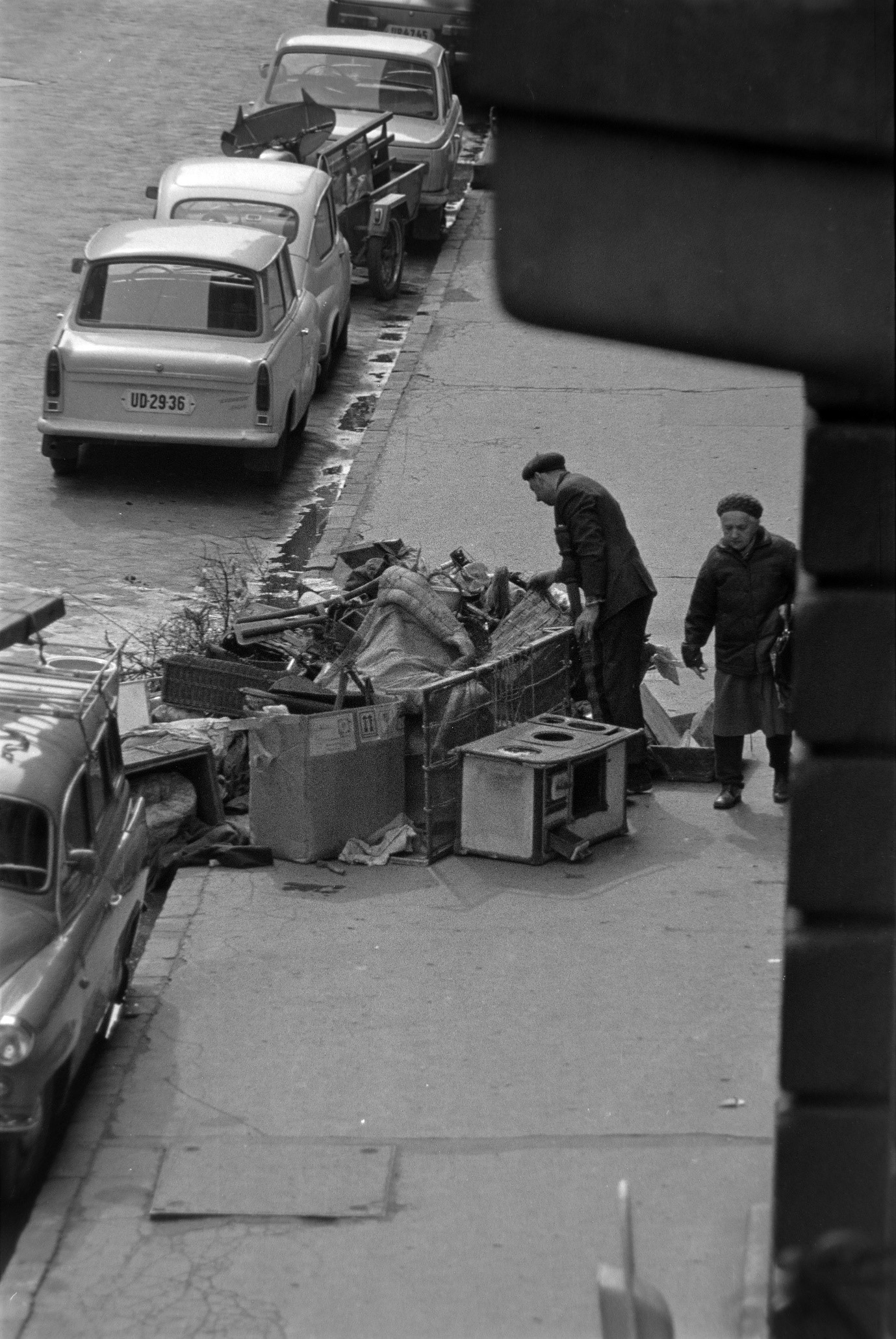

A few weeks later I returned home from teaching to see our street alive with people at nine o'clock in the evening. Of course, lomtalanítás: once or twice a year residents may put out on the pavement all their rubbish of the type not usually removed by the refuse collectors - old furniture, pipes, broken electrical gadgets, bicycle wheels, car batteries... any and every imaginable thing.

The dates for collection for any given area are published in the newspaper, and veritable hoards of ‘professional’ scavengers make it their business to be there from the moment the first piles of rubbish are dumped at the roadside. They moved methodically from one untidy heap to the next, carefully sifting through every item, extracting anything they could either use or possibly sell.

In the evening they brought torches, and like moles, scrabbled away in the darkness, their weak torch beams like faint glow-worms in the gloom.

As I passed the building next to ours there was a shout from above. ‘Hey you! Leave that stuff alone, it's mine!’ came the man's voice. It turned out that he was moving, and the pile of boxes and dilapidated furniture were his which he was taking up to his new flat. The man he had addressed reluctantly replaced his new-found treasure on top of the pile, and ambled off to the next heap, pushing an already heavily laden, rusty pram with bent wheels in front of him.

People searching through the rubbish Courtesy Fortepan/ Sándor Rubinstein

***

Before long it was Easter. ‘Well, are you coming to Böszörmény this year?’ Miklós asked me when we next met at Lingua. It had been a year or two since we had been, but it never failed to revive the vivid memories of our first real holiday in Hungary, the Easter of 1980, two years after Paul's two-month British Council stay. Little had we realised that in Miklós's family it was at least as big a celebration as Christmas.

His immediate family consisted of seven brothers (including himself), one sister, and his now elderly parents. Miklós was the only member of the family to have left the area. Apart from his younger brother Dani, all the siblings were married with their own families, and Easter was the one time of year when they all gathered together. Their numbers were swelled by one or two cousins, godparents and a maiden aunt. The total number was around thirty-five.

Miklós's parents lived in what we later found to be a typical, small country house: it was built on one level and stood at right-angles to the road. Thus, going through the large, old, wooden gate you stood at one end of the house, the main door being halfway along. The roof overhung the entire length of the building, creating a ground-level veranda, shady and cool in the summer.

Grapevines stood neatly tied to a fence alongside some colourful, untidy flowers, and from somewhere right at the other end of the house came the sounds of grunting pigs and clucking hens. Two thin, grubby cats lurked near the kitchen door as we approached.

Miklós's family was Greek Catholic and Easter was an important religious festival for them. They had already baked large loaves of kalács (a kind of milk bread) each with what looked like five flowers in the dough, representing the five wounds of Christ, as we were later told.

Those attending church on Easter Sunday morning took their bread to be blessed. The lamb which had been in the garden two days prior to Easter, had disappeared on the Saturday. When I asked what had happened to it, I was led to the kitchen where, by way of an answer, Miklós's mother pointed to the largest saucepan I had ever seen, sitting on the small stove.

The only door into the house led straight into the kitchen, from where a door opened on either side into the only two rooms in the house. Both rooms had a table stretching the entire length. Everyone arrived, formally dressed, the women crowding into the small kitchen to help, the men and children talking and laughing outside.

Lunch consisted of giant tureens of chicken and vegetable soup with fine noodles, roast chicken, lamb (stuffed with egg), potatoes, and then plate upon plate of many kinds of cake, the entire meal accompanied by equally generous amounts of wine and beer. Following the meal, the children ran outside to play, the women gossiped as they washed up in the kitchen, and the men reminisced on this and that, still drinking, a few smoking.

Easter Monday was taken up with a traditional, Hungarian folk custom. The girls and women paint and dye eggs; men, alone or in groups, together with their sons, go to visit all their female friends and relatives. Arriving at the home of a girl they say a short poem, usually about a flower wilting in the forest, and ask permission to water it.

Having been given permission, the boy sprinkles the girl's head with water or cologne and she in turn gives him one of the eggs she has dyed. This is, in fact, a rather genteel version of the original custom of dousing girls with buckets of water, though even today some boys arrive armed with a soda syphon. Men are also offered ham, eggs, kalács and cake to eat - and of course pálinka to drink.

On our first such Easter Monday, Paul was taken off by the seven Molnár brothers and assorted children while I stayed with his mother, sister and her teenage daughter.

By lunchtime my hair reeked of a dozen kinds of cologne. However, this proved a kind fate compared to Paul's: Miklós had told us that to refuse food or drink is offensive, and that as far as possible we should accept at least a small portion of whatever we were offered. Paul, anxious to follow this advice, had drunk the proffered glass - or three - of pálinka at every home the Molnár boys visited. It was thus that he returned firmly supported on both sides and only semi-conscious. He subsequently slept till the evening and felt only somewhat better by the next morning.

Village life - though Hajdúböszörmény is strictly speaking a town - was peaceful and calming. In the late afternoon, the day's work done, the elderly men in hats and with walking sticks, the women in boots and headscarves, would sit on the narrow, wooden benches outside their garden fences, surrounded by colourful flowers, the small ditch, sometimes with water, in front of them, and watch their friends and neighbours cycling or walking home from work.

Two women sitting on a bench in Hajdúböszörmény

Some would stop and talk about the prices at the market, their grandchildren or their ailments; others would just wave in greeting as they cycled slowly by. Some women sat and completed embroidery in the late afternoon sun, often accompanied by neighbouring women similarly engaged.

Many what we would consider ‘indoor’ activities were carried on outside. Miklós's father, sister and brother-in-law usually sat in the garden on low stools next to the grapevines in the mid-morning, peeling potatoes and chatting about family matters. Birth, marriages and death were still the central events of life, of conversation, and the passing of one of their number was announced by the prolonged tolling of the church bell, a different chime for a man or a woman.

There was never a sense of urgency: people strolled on the uneven pavements, horses and carts clattered past, their drivers asleep in the hay, the horse plodding his familiar way home; children with jugs walked to stand pumps for water, cats dozed by open kitchen doors always hoping for scraps, and the cockerel crowed a dawn which had long since passed.

***

Back in Budapest I decided that I would have to do something about getting a washing machine. I went to the shop I had been to with Endre, automatically taking a basket as I went through the door. Not that I was intending to put my machine into the basket, but it was a kind of entrance-ticket to a shop - you simply could not go around any shop without one.

There were even baskets in the record shop which, if you put a record in, prevented you from lifting up the handles, so the only strategy left was to tuck this unwieldy burden under your arm. Worse still in the record shop near the Music Academy, you were not allowed anywhere near the discs.

Having approached the counter and waited the customary four and a half minutes for the assistant to finish his chat or his coffee, you were asked what you wanted. Browsing was an alien concept even in most bookshops and when you re-emerged onto the street you had a pretty good idea of what they did not have in stock, but little idea of what they did.

The washing machine problem was solved some days later when Kálmán, to whom I had mentioned my intention of procuring another second-hand one, arrived one evening with a present. It was a rather small rusty tub, square, with a lid that sat on the top, like an oversized saucepan. It had to be filled with water of the requisite temperature with buckets, the lid put on, and the timer set to the required number of minutes.

It was then plugged into the wall and began to gyrate noisily. When it was finished you unplugged it, threw the dripping clothes into the bath, and then positioning a spout at the front of the machine over the drain in the floor, tipped it so that the water came out. It even made my mother's antiquated twin-tub look space-age, and like the machine in Garay tér this too found its final resting place in the bathroom when we later moved away.

Washing machine

Another feature of daily life was the schizophrenic attitude towards queuing. In many places it was necessary to queue three times: once to ask for what you wanted, again at the till to pay, and a third time when you joined the line of people waiting to have their purchases wrapped. However, in offices or doctors’ surgeries the procedure was quite different. The strategy was to position yourself as near as possible to the door, which usually meant standing, and then leaping forward as soon as the door opened.

However, there were many variations on this game - walking straight in (with maybe a cursory knock) without any regard to the others waiting, pleading that your last train home was leaving in half an hour and you must be seen immediately, or saying that you merely wanted to ask a quick question of someone inside, but of course then having your whole case dealt with.

At the end of April we began to hear rumours that there had been a serious atomic explosion in the Soviet Union, and that radioactivity was spreading all over Europe. There was, as yet, nothing in the Hungarian media - it seemed that even Gorbachov's glasnost and perestroika had difficulty in coping with this turn of events - but the BBC World Service confirmed the story. Laurence called in the same day.

‘Let's switch off the lights and see if we glow in the dark,’ he suggested. Budapest was, within a day or two, a giant grapevine along which Chernobyl-related jokes passed back and forth. The British Embassy relayed guidelines about not eating leafy vegetables, while at the Lehel tér market the sign advertising ‘atomic strength paprika’ had had the first word crudely struck through, and in other parts of the market ‘radiation free’ lettuces were to be had.

Film: Chernobyl in Hungary – checking radiation levels at the market

With May came the spring. To anyone from England the temperatures more closely resembled summer, but the sudden bursting into bud and flower of every plant, bush and tree, the almost hysterical fervour of birdsong and the pulsating, surging renewal of life always made me think of Stravinsky's Rite of Spring.

It could not have been the bright, crisp sun and gentle showers of England he had in mind when he wrote the work. I could now understand it in a way I never had before. The same was equally true of Kafka's novels, I sometimes mused.

Click here for earlier extracts

Main photo: ‘Lomtalanitás’ - Courtesy Fortepan/ Tamás Urbán

LATEST NEWS IN community & culture