Now On: Cézanne & The Past, Museum of Fine Arts Budapest

- 4 Dec 2012 8:01 AM

The exhibition displays some one hundred of Cézanne’s works, including numerous compositions which the master drew based on his studies of works by the old masters. The works by the old masters will be displayed next to Cézanne’s paintings, water colours and drawings to clearly demonstrate through the discovery of similarities and differences both the impact of the old masters on Cézanne’s art and the power of his composition.

For a century now Cézanne has been seen as an artist who encapsulated the painting of the previous centuries and founded modern art. In relation to this the exhibition explores how Cézanne discovered the art of the old masters for himself and in what way this helped him to create that of his own. Throughout his life Paul Cézanne studied the works of his great predecessors. He made direct copies, borrowed motifs and analysed the compositions.

In museums and in the art of his contemporaries he searched for clear ideas expressed by others that would inspire him. However, he was left feeling dissatisfied after merely translating these works into his own “language”; and so instead, while developing his own art, he elaborated those ideas hidden in the works of his predecessors that were important to him. After this, where he deemed possible, he incorporated the elements he discovered into his own works.

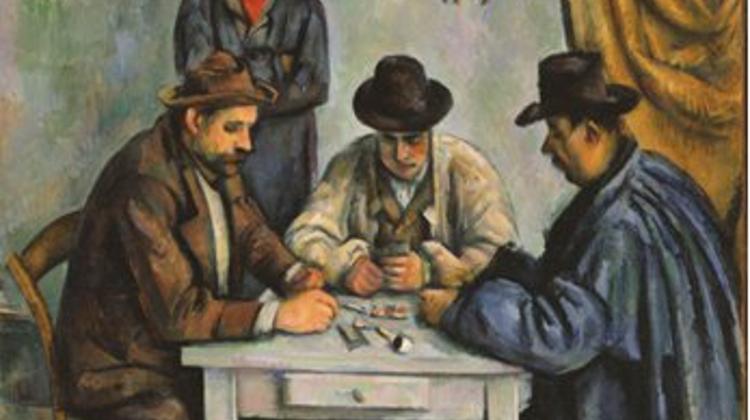

Through the chief works showcased at the exhibition, such as the Parisian Card Players (1893-96, Musée d’Orsay, Paris) and the New York Card Players (1890-92, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), Montagne Sainte-Victoire (1882, The Courtauld Institute, London) and Montagne Sainte-Victoire with Large Pine (Phillips Collection, Washington D.C.), Harlequin (1888-90, Washington, National Gallery of Art), The Bathers (1899/1904, Chicago, Art Institute), Kitchen Table (1888-90, Musee D’Orsay, Paris) and Madame Cézanne in a Red Armchair (1877, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) Cézanne’s ties to the traditions of classical painting take shape, while his own voice and creative artistic genius are revealed.

In the exhibition the work of art by Cézanne’s predecessors are displayed next to his own, allowing us to find the affinities between them or discover the differences. This facilitates an understanding of why the French master selected these works upon which to base his own, how long these compositions and motifs influenced him, and how often and in how many versions they turn up again and again.

Through the chief works showcased at the exhibition, such as the Parisian Card Players (1893-96, Musée d’Orsay, Paris) and the New York Card Players (1890-92, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), Montagne Sainte-Victoire (1882, The Courtauld Institute, London) and Montagne Sainte-Victoire with Large Pine (Phillips Collection, Washington D.C.), Harlequin (1888-90, Washington, National Gallery of Art), The Bathers (1899/1904, Chicago, Art Institute), Kitchen Table (1888-90, Musee D’Orsay, Paris) and Madame Cézanne in a Red Armchair (1877, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) Cézanne’s ties to the traditions of classical painting take shape, while his own voice and creative artistic genius are revealed.

Cézanne deservedly occupies a place among the greatest masters in the history of art, yet the public at large are familiar with only a narrow selection of his oeuvre. However, the Budapest exhibition that is soon to open seeks to provide one possible interpretation of his artistic path spanning four decades through a special approach to his work – by examining Cézanne in the context of his ties with the masters he held in great esteem.

In the first section of the exhibition visitors can admire two of Cézanne’s masterpieces – his painting titled Montagne Sainte-Victoire with Large Pine, depicting a mountain in the vicinity of Aix-en-Provence, and its London version – placed in a unique context. The historical framework for these two important landscapes of Cézanne’s oeuvre are provided by Nicolas Poussin’s Landscape with the Ashes of Phocion and George Braque’s Park Carrières-Saint-Denis; thus, one of the most important themes of the Budapest show comes into focus at the beginning of the exhibition, namely the role the great masters may have played in the development of the organic system of Cézanne’s art.

The portraits (sculptures, paintings, drawings and prints) linked to Cézanne’s private life as well as to his circle of friends from his adolescent years and the artists he met in his youth are shown in parallel with the development of his oeuvre in a somewhat supplementary way. The Budapest show is, after all, the first Hungarian exhibition of Cézanne; thus, visitors need to be given a biographical context for the groups of works arranged according to a scientific concept.

Cézanne’s early works can be seen in a separate section, helping visitors to form a picture of the painter’s developing drawing skills and to comprehend which of his predecessors he chose as models in this period. Later, in the 1870s, Camille Pisarro exerted a major influence upon Cézanne. The two artists studied the old masters together and this further shaped Cézanne’s artistic approach. The still lifes that came into being between 1877 and 1906, including the recently restored Buffet from the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, are displayed in a separate part of the exhibition.

The landscapes, which beautifully exemplify Cézanne’s individual expression, can also be viewed in a separate chapter. Breaking away from tradition the master called himself the “conscience of the landscape” and rejecting the aerial and linear perspective he professed that the mass of forms and clarity of colours should be accorded equal rank in every point of a picture. Here Cézanne’s ties to the old masters are contextualised through works by Poussin and other artists.

Also displayed at the Budapest exhibition are Cézanne’s two compositions titled The Card Players: a two-figure version preserved in the Musée d’Orsay in Paris and a four-figure version from the collection of the New York Metropolitan Museum, together with works by Le Nain and Daumier regarded as their archetypes, while a parallel is drawn with works by Ostade.

Cézanne’s late portraits and the preliminary studies made for The Bathers are also allocated a separate part of the exhibition, as well as three versions of the composition which according to the art historians studying his oeuvre “represent the greatest heights of Cézanne’s constructive way of painting”.

As the closing chord of the exhibition those players appear (e.g. Charles Baudelaire, Julius Meier-Graefe, Roger Fry, Louis Philip and Simon Meller) whose writings contribute towards an interpretation of Cézanne and his ties to the old masters.

The essays in the exhibition catalogue were written by such notable scholars of international Cézanne research as Richard Shiff, an American expert on 19th century French painting, Caroline Elam, a professor of art history at the Harvard Center, Mary Tomkins Lewis, the former editor of Burlington Magazine, Cézanne monographers Inken Freudenberg and Peter Kropmanns, a researcher at Oxford University, Linda Whiteley, the curator of The Courtauld Institute of Art, Nancy Ireson, museum director Lucas Gloor and professor of art history Klaus Herding, as well as Isabelle Cahn, the curator of the Musée d’Orsay.

Cézanne’s art is showcased at numerous exhibitions in prominent museums of the world year in year out; these being engaged in a constant dialogue. The Budapest show will now join this dialogue in order to contribute to a better understanding of the artist and to provide a picture of him to the people of today.

The exhibition was directed and the concept elaborated by Judit Geskó, the director of the Museum of Fine Arts’ Collection of Art after 1800, and the curator of the shows Monet and Friends, which opened in 2003, as well as Van Gogh in Budapest, staged by the museum in 2006.

The exhibition has come into being thanks to the exclusive sponsorship of the Hungarian subsidiaries of the ING Group, which supported with HUF 120 million.

On display until 17 February 2013

Source: Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest

Dózsa György út 41, 1146 Budapest

Telephone: +36 1 469 7100

LATEST NEWS IN travel