An Englishwoman's Life in Communist Hungary: Chapter 3, Part 5.

- 3 Jan 2023 12:51 PM

Now You See It, Now You Don’t and House of Cards have been included as part of the Open Society Archive dedicated to this period in the CEU. You can read a serialisation of them here on Xpatloop. You can also buy the dual-volume book on Kindle as well as in Stanfords London.

Chapter three: Market and May Day: Garay tér

Part 5 – ’Chicago’ life; flight ticket purchase complications

Six weeks after we had moved in my mother came from England for a holiday. I had opted out of most of my teaching commitments for those two weeks, though there were one or two lessons I could not find anyone to substitute. It was after an afternoon of teaching that I returned to the sound of raised voices as I opened the door to the flat.

Walking into the room I saw a small circle of chairs, and sitting there was Rózsi-néni, looking quite unmoved by the shouting, Paul looked worried, my bewildered mother - unable to understand a word - and Zoli-bácsi , extremely agitated. In the middle stood Endre, pacing back and forth, gesticulating expansively and giving me only the merest hint of a smile before continuing with his speech.

The others were so riveted they hardly seemed to notice that I had arrived. Apart from a few outbursts from Zoli-bácsi, Endre continued unabated for maybe fifteen minutes, stopping only once to grin at my mother and say in English, ‘Don't worry, it'll all be okay,’ before continuing his vehement argument.

I sat down next to my mother who whispered that this had been going on since half past one. I glanced at my watch: just past three o'clock. About fifteen minutes later Endre seemed to be reaching some kind of conclusion, and reluctantly Zoli-bácsi and Rózsi-néni got up to leave.

Endre saw them out and returned, all smiles. ‘What was all that about?’ I asked.

‘Zoli-bácsi says we've got to leave the flat,’ said Paul.

‘Why?’

‘Don't worry, you don't have to leave,’ said Endre, ‘but I think you should have something in writing. I've told him he's got a month to make up his mind, and then we'll make out a contract for a year. But don't worry, they wouldn't want to give up the money.’

Little by little the main points of the conversation were repeated to me, the most extraordinary factor being that Zoli-bácsi had mentioned the possibility of getting divorced from Rózsi-néni and coming to live in the flat.

He was seventy-eight, she seventy-six, and he could hardly walk up the stairs from the street, he was frail and could hardly see; it would be quite impossible for him to manage alone.

As usual, Endre was right. A month later they returned and signed the contract Endre had prepared. No mention was made of divorce, and Zoli-bácsi agreed to come to the flat only to collect the rent.

As they left, our neighbour passed the door and exchanged a few words with Rózsi-néni. Zoli-bácsi hung back in the hall; taking Paul to one side I heard him say softly, ‘It's my wife who doesn't want you to stay here, not me.’ Then shaking Paul by the hand, he joined Rózsi-néni and they slowly made their way down the stairs.

Garay tér and its surrounding area were commonly known as 'Chicago'. When I told anyone that we were living there, they greeted the information with surprise and distaste.

It had become a focal point for Poles, gypsies, alcoholics, tramps and dubious business.

A large supermarket bordered one side of the market, and it was there that the Poles gathered. Having been deposited at Keleti station nearby, they carried their assorted bags and suitcases of bric-a-brac to sell outside the market.

It seemed that literally anything could be bought and sold there: bottles of cognac, second-hand underwear, clothes, furs, old shoes and boots, quartz watches, baskets, broken toys and dolls, leather jackets, deodorant sprays - anything at all.

Bargains were struck in the dust on car bonnets; prices written then erased and a lower price drawn, only to be crossed out again, and so on, until a final amount was agreed.

Then they spent their forints on food and carried their laden suitcases back to Keleti station. Often there were so many of them that getting in and out of the supermarket was all but impossible. More than once it happened that someone wanted to buy my shopping bag as I fought my way through the crowd.

The alcoholics and tramps congregated just inside the main gate to the market. They seemed to spend the greater part of every day collecting cardboard which could either be sold or used for bedding. They sat, often quarrelling loudly, next to the window where empty deposit bottles were returned to the supermarket.

As the market was locked at night they obviously did not sleep there; maybe they slept in the cellars of surrounding buildings, but when the market was open they were there, and I came to recognise them. One man with two walking sticks I had frequently seen sitting begging in the underpass at Keleti station.

But here in Garay tér, leaving his sticks with his compatriots outside, he strolled into the supermarket filling his basket with bottles of beer.

Somehow, the women were a more disturbing sight than the men. They looked dirtier, quarrelled and even fought more, and I wondered what chain of events had led them here.

Further inside the gateway were the gypsies, mainly women and their teenage daughters sitting on the ground, wearing huge skirts and gaudily coloured headscarves and aprons, and surrounded by babies and young children.

They offered quartz watches and watch batteries for sale, calling to anyone passing while continuing to breast-feed their children anywhere up to the age of five.

Garay tér Courtesy Fortepan- Sándor Kereki

Inside, the main area of the market consisted of fruit, vegetable and meat stalls. These were supplemented with a fish stall selling carp and fish soup - delicious if you have patience and are not too hungry to pick your way through the hundreds of bones (sea fish is unknown, Hungary being a landlocked country); a mushroom stall where people who had picked their own in the hills, can have them examined and are given a certificate declaring them safe, which is always displayed alongside the mushrooms; a small shop selling beer, wine, soft drinks and tins of food - where I found the only tinned salmon of our stay, and a small shop with everything from French perfumes and Scotch to bottles of Heinz ketchup and Worcester sauce.

The majority of the stalls were supplied by various state-owned enterprises, but around the perimeter were smaller stalls and tables behind which sat people from the country: leathery, brown hands, deeply wrinkled faces, men in leather waistcoats, long boots and hats, and women in multitudinous petticoats and headscarves.

Their produce was usually of better quality and slightly more expensive, and was carefully laid out before them: a basket of eggs (free range), a chicken, maybe a duck, jars of honey, small bunches of parsley carefully tied up, carrots, yellow paprika - all types of vegetables and fruit according to the season.

It took us a while to adapt our cooking to the seasons, after the availability of everything all the year round in England. The drop in price at the peak of the season was also something unknown to us: tomatoes for example, in March and April cost a good three hundred forints for a kilo, but by September they were a mere six forints.

A small, covered area of the market was given over to stalls of flowers and plants which people brought from their gardens.

From the windows of our flat the whole square was spread before us. While we ate breakfast we could see the throngs of Poles bargaining outside the market, the gypsies inside, the loading, unloading, and the queue on the steps of the Palm Cukrászda; then occasionally the crowd of Poles would disperse, some into the market, some into the supermarket, while some strolled off down the road.

Others gazed nonchalantly into a nearby shop window, pointing things out to the person standing next to them.

Then, from the far corner of the square, two policemen would saunter past the supermarket and occasionally through the main gate, but it was rare that they caught anyone. If they did, it was usually because they had come by car, and obviously whatever method of signalling a police presence operated in the square, it could not be carried out fast enough.

Our neighbour, Feri-bácsi, a retired coach driver, was almost as permanent a fixture on one corner of the square as the phone box was on the other.

He would happily stand and watch the comings and goings from after breakfast until lunch, while in the afternoons he was frequently to be seen attending to his newly-acquired Skoda parked nearby. Or he would lean on the bonnet of the car parked outside Imre's workshop while Imre himself, oily rag in hand, continued to clean some spare-part, nodding every now and then as Feri-bácsi held forth.

They were known to everyone on the square and knew everyone, so it came as no surprise to us (though it amazed those involved) when someone trying to find us asked a person standing in the street, ‘Where do the English people live?’ and they received the immediate reply with outstretched arm, ‘Up there’.

The flat became hotter and hotter as May turned into June, and we began to make plans for going home for the summer. We had to hand in our identity cards and passports in order to obtain our exit visas; it seemed strange, that, like Hungarians, we could not leave the country without visas, costing us four hundred forints each for the privilege.

Next, we found the British Airways office to buy our tickets.

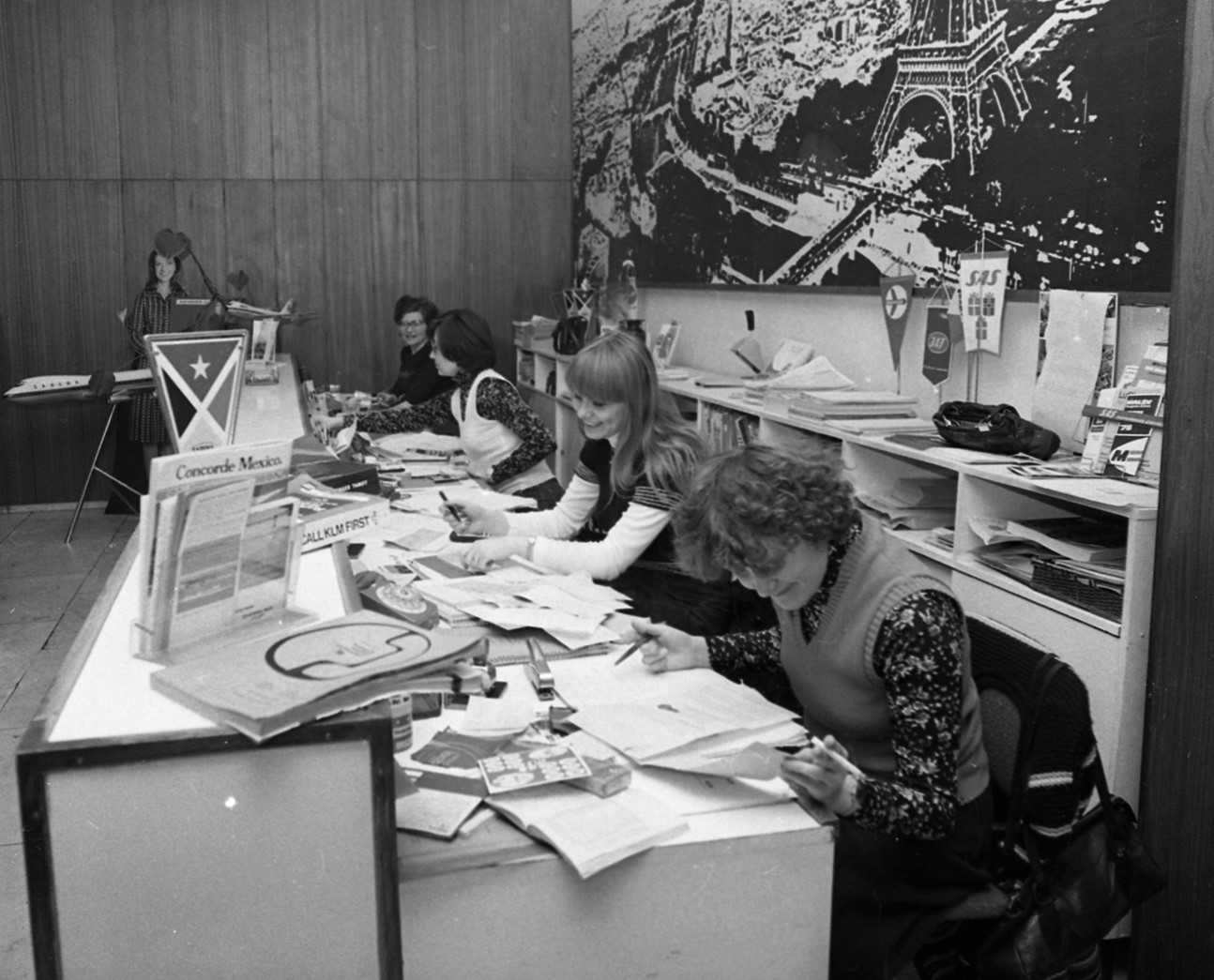

Travel Agent Courtesy Fortepan / Magyar Rendőr

‘What kind of passport are you travelling on?’ asked the immaculately dressed woman behind the desk. ‘British,’ I replied.

‘Well, if you travel before July 1st, it will be one hundred and fifty-seven pounds.’

‘I would like to pay in forints.’

‘I'm sorry, if you're travelling on a British passport that's not possible.’

‘But we work here. We're not attached to the Embassy or anything and we only earn forints.’

She looked unconvinced, but handed me a form and said, ‘You should go to the Hungarian National Bank with this, and if they stamp it for you, you can pay in forints. Do you know where it is?’ She explained how to get there, and made seat reservations for us.

The National Bank was an imposing building in Szabadság tér dominated by the TV headquarters and the American Embassy. After showing our form to various people, we were directed to a window where no-one else was standing.

We began trying to explain our predicament. The woman turned the form over and over shaking her head, while asking us to produce our ID cards. We explained that we had had to hand them in to get our visas.

She smiled and shook her head again, it was obvious that there was no point continuing this until we had our papers back.

Hungary’s National Bank Courtesy Fortepan/ UVATERV

Some days later, after repeated phone calls to KEOKH (the office dealing with foreigners), we had our visas, ID cards and passports back.

This time a man was sitting behind the glass at the bank, and it appeared he had never seen such a form before. He read it carefully, then disappeared with it for some ten minutes before returning and saying he could not stamp it for us.

Time was getting short. We should already have paid for our tickets and if they now refused to allow us to pay in forints, it would take us still more time to get enough hard currency together.

We went back to the Academy where we were obligingly given a photocopy of Paul's contract and a covering letter, but these were also rejected. The man at the bank then asked if we had tried the main police station near November 7th tér, so mentally writing off the rest of the day, we thanked him and left.

Click here for earlier extracts

Main photo: Bargaining at Garay tér Courtesy Fortepan/ Sándor Kereki

LATEST NEWS IN specials