'An Englishwoman's Life in Communist Hungary': Chapter 4, Part 4.

- 3 Apr 2023 6:03 PM

Now You See It, Now You Don’t and House of Cards have been included as part of the Open Society Archive dedicated to this period in the CEU. You can read a serialisation of them here on Xpatloop. You can also buy the dual-volume book on Kindle as well as in Stanfords London.

Chapter four: Courtyard and Characters

Part 4 – ‘Guy Fawkes’ in Budapest; teaching on a collective farm

Another new friendship began very soon afterwards. We were contacted to do a recording at the Pannónia film studios, a voice-over for some advertisements. As we walked into the sound technicians' room we heard the very distinctive, gruff voice of someone doing an ice-cream advertisement.

This was Harvey, Mr. Harvey as the technicians called him. He only had one sentence to do but the producer had very definite ideas about how it should be done. It seemed fairly obvious to me that Harvey's laughter would soon turn to hysterics unless he had a break. ‘Let's have a coffee,’ said the producer, reading my thoughts.

We adjourned to the café‚ and found that Harvey had been in Hungary quite a few years already and was married to Regina, a doctor and a specialist in rheumatism. He also had two young sons. Before we left that day, he had invited us to visit them at the weekend. We very much took to Regina and thus another friendship started.

June in Hungary is the month of exams and school-leaving celebrations. Especially in secondary schools, though in primary and even nursery schools, traditional celebrations are held to mark the rite of passage from one school to the next.

Teenagers wearing suits, girls in black skirts and white blouses and parents in elegant attire can be spotted all around the country at any time in May or June. Relatives, parents and friends, laden with bouquets of flowers, make their way to say their final farewells to school friends and teachers. It is also the tradition for pupils leaving school to go to the homes of their teachers and serenade them.

Thus it was, that one evening sitting in our flat, we heard singing resounding around the courtyard. Looking up I saw a group of students I had taught at Lingua, standing on the walkway, outside our windows.

School leaving ceremony

Among them was Geoff - another Zoli in real life, but it was Lingua's tradition to give their students English names. He was quite the most gifted student I had taught and would now be going on to do an English degree at Budapest's ELTE university.

His parents were both musicians and quite coincidentally lived in the same block of flats as Lingua. His mother had been the one who had arranged Paul's job and work permit, in her capacity as personnel officer at the Music Academy. They had become a second family to us and I often went down from the sixth floor at Lingua to their second-floor flat when I had time between or after lessons.

They had witnessed my first, faltering attempts to speak Hungarian and had not been able to stop themselves laughing, though they were always patient and encouraging. Little did I then realise that some five years later Geoff and I would be teaching together as colleagues.

My cello teacher Zoli was also leaving the Academy, as was Paul's erstwhile student Tamás, who used to swap recipes with him. Zoli, now married, had managed to get a job playing in a palm-court orchestra on an island off West Germany called Borkum. It was sad for me to lose him both as a teacher and friend, though he promised to find me another cello teacher and to keep in touch.

Meanwhile, Tamás had no chance of passing his English exam, and without it would not be awarded his diploma. He arrived one evening to beg us to give him private lessons, something Paul had so far not done for anyone, fearing the deluge that would ensue if word got round. ‘I can't pay you for the lessons,’ Tamás explained, ‘but I can come and clean your flat, cook, anything you like...’ It was impossible to refuse.

We agreed that the ‘fee’ for the lesson would be to play to us afterwards. However, since we always had our meal at that time in the evening and we invariably ate together with Tamás the arrangement soon lost any pretence at formality and he became a firm friend.

He was intending to play the Tchaikovsky violin concerto for his diploma recital and suggested playing it at the end of one of his lessons with us. The lack of either an orchestra or piano led us to suggest that we should sing the orchestral interludes. Our enthusiastic, though increasingly frantic attempts, caused even Tamás to break into uncontrollable laughter.

Temperatures began to soar as June turned to July and we prepared for our annual visit to England. Laurence was also spending the summer with his parents and we agreed to spend a few days together during the holiday.

We visited Sue and Steve in Cambridge, now with a second baby, our parents, and other relatives and friends. Then we travelled by coach to Chester where Laurence picked us up and drove us to his parents' on the English-Welsh border.

His father, George Roman, was the director of Welsh National Theatre, and his mother Judy was completing work on her thesis for a Ph.D. in philosophy. When they left Hungary in 1956 they spoke hardly a word of English; they were an extremely talented family. Laurence himself was busy finishing an opera commissioned by English National Opera, and after his year as a composition student at the Liszt Academy, had been asked to teach composition there.

We spent three memorable days in their company, playing through the whole of Laurence's opera to George in one of the theatre's practice-rooms, eating Judy's wonderful creations and having passionate discussions about Hungary with George.

We returned to Budapest early in September and began teaching almost at once. It was still very warm and we looked forward to more autumnal weather. Spring and autumn were usually short and often rainy, though it was rare for a day to pass quite without sunshine.

Most Hungarians hate rain and were ill-prepared for it when it came. They always reminded me of cats gingerly picking their way through the puddles - often with plastic bags over their hair in lieu of an umbrella.

Rain, with improvised umbrellas Courtesy Fortepan/ Tamás Urbán

Late in October I bumped into Caroline in the street. ‘I'm glad I've met you,’ she said, ‘I was going to write you a postcard inviting you both to our Guy Fawkes party. We always have one for the boys. Of course, we can't get fireworks, but we make a guy and a bonfire and I've got some sparklers left from last Christmas.’

The party was on the Saturday after the 5th of November, and two other English families came with their young children who gleefully drew patterns in the dark with their sparklers while we drank hot mugs of curried apple soup.

‘Have you done this every year?’ I asked Caroline as we stood by the fire.

‘Yes. But we nearly got into trouble a year or two after we started,’ she replied. ‘Our neighbours came round and said if we didn't stop doing this every year they would go to the police.’

‘Why?’ I asked incredulously.

‘They thought that the guy, with his moustache, was Lenin, and since Guy Fawkes is so near to November 7th, they assumed we were burning Lenin on the bonfire every year,’ she said. ‘I had to give them a quick English history lesson to avoid being reported,’ she laughed.

Miklós and János had persuaded me to do a week's teaching on a new course at a state farm in a village near the Romanian border called Mezőhegyes. ‘Now, you'll have to catch three trains to get there,’ explained Miklós.

‘First you go to Békéscsaba, change and catch the train to Orosháza which you've done before, and from there you get the train to Battonya which stops in Mezőhegyes. One of the students, a vet called Laci, will meet you at the station.’

It was already late November when I went. By the time I arrived in Békéscsaba it was dusk and once in Orosháza it was pitch black. I found the Battonya train and hauled my bags of books up from the ground below.

As usual in country stations there were no platforms. We pulled out of Orosháza station, stopping again some ten minutes later. I peered out into the total blackness thinking the signal must be red. But no, doors slammed, people got off and others on with no sign of a building, a light or human habitation in sight.

The train was now quite crowded with country people carrying bags of food and wine, and one with a duck or possibly a goose which occasionally stuck its head out of the covered basket in which it was being transported.

Again the train stopped in the middle of nowhere. Turning to a fellow-passenger I asked, ‘Is this Mezőhegyes?’

‘No, not yet,’ came the reply.

‘Do you know how many more stops it is?’ I asked again, fearful of missing it altogether.

The woman turned to someone else, ‘How many stops to Mezőhegyes?’ she asked in turn. The other shrugged. He did not know how many stops it was but he said he would tell me when we got there. Every time the train slowed down I looked with anticipation at the elderly man until he finally nodded, ‘This is it.’

Mezőhegyes station

There was only one person waiting on the platform, so I boldly walked up to him and enquired whether he was Laci the vet. He was. He spoke Hungarian with alarming velocity, but I had long ago mastered the art of nodding in the right places, so I settled myself in the car while he drove to the farm's holiday-home where I would be staying.

It was a small, low building with about six rooms, and after depositing my bags we continued to his home. There I met his wife Alice, who was also on the language course, and their two sons. Alice spoke quite reasonable English, so in a mixture of both languages we had a good supper together, which was then interrupted by a knock at the kitchen door.

It was a man from the farm to say Laci was needed to assist at the birth of a cow, the car was waiting outside. Of course, I reminded myself, no phone. In fact, I later learned that only the doctor had a phone and only one public telephone existed in the whole village.

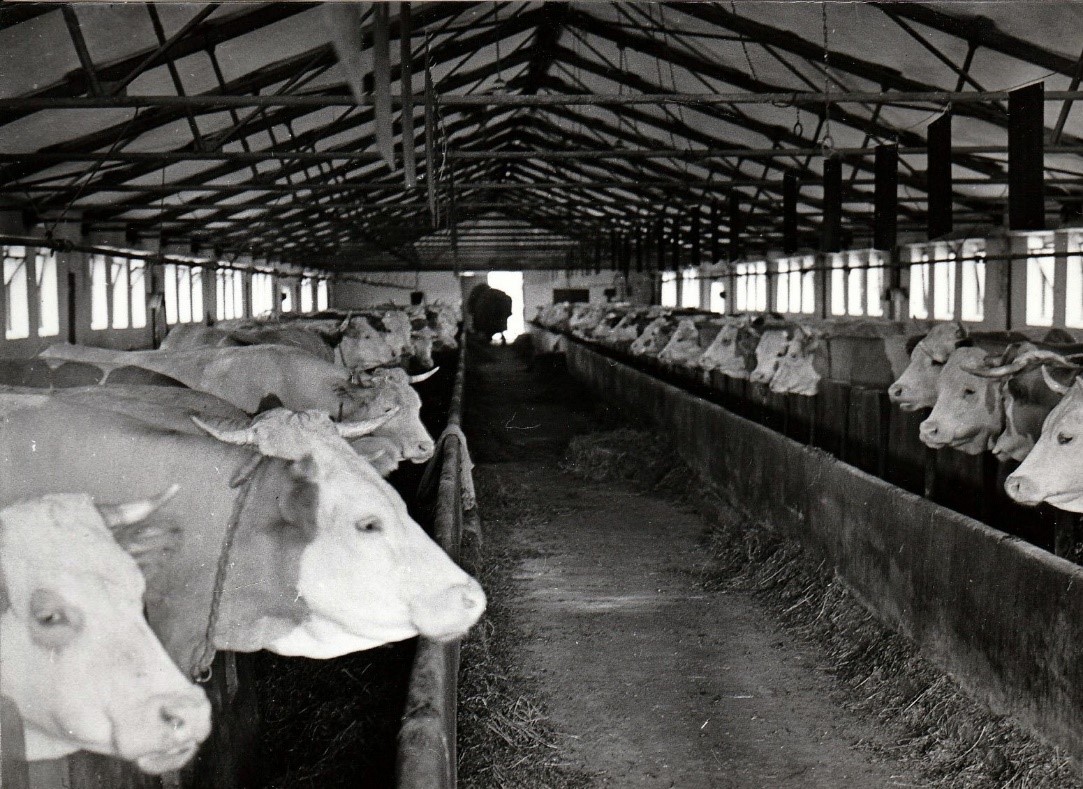

Standing up and looking at me Laci asked, ‘Coming?’ I nodded, leaving my unfinished wine and waving a quick goodbye to Alice. We were driven at speed over a bumpy, unmade road towards nothing more than a faint glow in the distance, finally stopping at a large farm outbuilding. Inside it was warm and damp, and as we walked towards the men surrounding a groaning cow at the far end of the barn, I saw a cat nursing its kittens in the straw of an empty stall.

Laci's friendly, easy-going manner changed instantly as he rattled out orders to the men, rolling up his sleeves to examine the cow. I was given to understand that it was to be a Caesarian, but that it is dangerous for cows to lie down and they can therefore only be given local anaesthetic.

The cow's flank was sprayed, several injections given, and then Laci made the first incision through the cow's hide. Following this, he had to cut through layers of muscle. It was at this point in the proceedings that I began to feel strange. I am not squeamish, but the sight of the cow turning to watch itself being cut open proved too much, and to my great chagrin I realised I was about to faint.

I came round a few minutes later in a small area off the main barn, sitting on a bale of straw in the company of the man who must have carried me there. He stood grinning at me and offered me a glass of water. Luckily, I felt well enough to walk back in time to see the calf emerge from its mother, now too preoccupied with her offspring to take any notice of the stitching in which Laci was engrossed.

Click here for earlier extracts

Main photo: Pannonia Film Studios - Courtesy Fortepan/ Sándor Bojár

LATEST NEWS IN community & culture