An Englishwoman's Life in Communist Hungary': Book 2, Chapter 2

- 26 Sep 2023 7:03 AM

Now You See It, Now You Don’t and House of Cards have been included as part of the Open Society Archive dedicated to this period in the CEU. You can read a serialisation of them here on Xpatloop. You can also buy the dual-volume book on Kindle as well as in Stanfords London.

Book Two, Chapter two: First Cracks

Part 2 – Éva

Margaret Island was a haven of tranquillity. On weekdays it was all but deserted, just the odd couple walking hand in hand under the immense plane trees, a few mothers like me, and one or two earnest-looking joggers.

‘Who’s that man chasing?’ John asked as one such jogger trotted past us.

‘No-one,’ I replied.

‘Why is he running?’ came the logical next question.

‘He’s just running. He likes running,’ I said. John was puzzled. He was not a particularly active child, he was heavily built and far preferred to sit in the pushchair than to walk.

Autumn was in the air. The gardeners were digging up the bushes from the island’s rose garden, the swimming pool lay drained, a few leaves floating in puddles at its base, the gates to the open-air theatre stood padlocked, the posters removed from its walls, and the booths selling ice-creams and postcards were tightly shuttered.

*

Miklós had returned from Bloomington. Miklós, who in 1978 had been called out of his English class at the Karl Marx University of Economics to meet the Vienna train, and act as interpreter to Paul on his first visit to Hungary.

Paul was to do research work at the Liszt Academy for two months, and Miklós – in common with almost all Hungarians – counted on such part-time work to supplement his meagre university salary. Miklós and Paul had become friends and after the official three days for which Miklós was employed to interpret, continued to see each other daily.

He visited us in England, and we returned on holiday and met his family in Hajdúböszörmény – his elderly parents, six brothers, one sister and countless nieces and nephews. It was Miklós who, together with his closest friend János, had set up Lingua, where I worked for the five years before John was born.

I was not alone in noticing the changes to his personality which had taken place in the year just spent in America. He was restless, impatient, and seemed to have serious problems readjusting to life in Hungary.

It was not just the year’s absence that had caused this, but the fact that he had returned to a country profoundly changed from the one he had left in 1988, and one where there was still no clear concept of where things were heading.

None of our friends had ever lived abroad, and the perspective it gave Miklós on life in Hungary was one he felt unable to share with anyone but myself. We met regularly, and as I listened to his tales of life in provincial America, I realised how some of his apparent bitterness sprang from his many disappointments in a country he had previously held so much in awe.

‘You know,’ he said to me one day, ‘you English have a lot of nasty little prejudices about America.’ He paused. I sighed my acquiescence. ‘And you know what?’ he continued, ‘you’re absolutely right.’

I was now teaching at Lingua every week. I had now also met Éva who lived opposite us, who asked if I would be interested in teaching a small group of doctors, including herself. Most of them were consultants in various hospitals and unashamed anglomaniacs.

‘Why don’t you come over this evening when the children are asleep and we’ll talk about it?’ she said.

Later, quietly closing our front door behind me, I stood alone in the long dark corridor, listening. Below me I could hear the heavy bang of the lift door before it noisily clanked its way further downwards. It was accompanied by the metallic grating of someone opening the refuse chute - to be found on every floor - and the noise of rubbish hurtling its way to the bins on the ground floor.

The small rooms where the chutes were located stank, while the descending refuse invariably caused a cloud of ashen dust to puff out of its mouth at you, unless you could slam it shut immediately after letting go of your rubbish. The chute itself was said to be infested with cockroaches due to the constant food and warmth that it provided.

The end of the chute that carried rubbish down from all floors of the building

I knocked at Éva’s door. She led me through the small hall and into the main room. Without pausing to look around I walked straight over to the window and gazed out. Leading from below us to the other side of the Danube was Árpád híd, a blaze of white headlights coming towards us, a stream of red tail lights blurring into the distance.

The bridge touched the northern end of the Margaret Island, now darkly shadowed, its thick trees crowded together, a black forest reflected in the flickering lights on the water’s surface.

‘Beautiful, isn’t it?’ she almost whispered.

View from Éva’s flat across Árpád bridge at dusk Courtesy Krisztián Bodis

The Buda hills stretched as far as one could see in either direction: charcoal arcs etched against an indigo sky, a hundred thousand pinpoints of light glinting forth.

‘It makes it worthwhile living in a building like this for a view like that,’ I said, nodding outside.

‘Yes,’ replied Éva, ‘and when we came to live here the flats all cost the same whichever side of the house they were on.’

I turned now for the first time into the room. ‘Yours would be worth much more now than ours.’

Éva smiled. ‘I’ll bring some tea. You do like Earl Grey, don’t you?’ she asked, making for the kitchen.

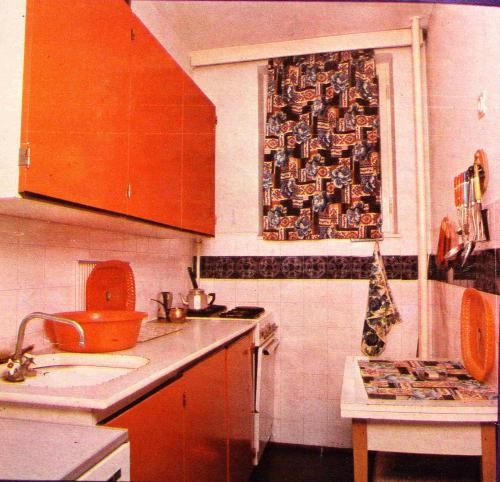

Typical kitchen in a ‘panel’ block

I had not paid much attention to the room as I strode through it to the window, but now I marvelled at its cosiness.

I had been in countless such flats, but none had conjured up that warmth of atmosphere I associated exclusively with the old buildings I loved.

Bookshelves lined one whole wall from floor to ceiling, postcards wedged between their volumes, statuettes balanced on their edges, and both literary and medical journals were crammed in any space still available.

Worn, hand-woven rugs covered the floor, and in the centre of the room stood a rickety wooden table with an uneven and rough surface. The two antique armchairs looked rather unused, while the sofa in the corner, covered with a coarse white blanket and littered with tapestry cushions, dimly lit from above by a reading lamp, was probably Éva’s regular seat.

I perched myself unsteadily on a straw-covered stool by the table, and Éva arrived with the tray. She poured the scented tea into chipped, flowery, Herend teacups.

I had not yet alluded to her husband’s death, but I felt I could not leave it any longer. ‘I’m so sorry about your husband,’ I began, looking up from my tea.

‘You didn’t meet him, did you?’ she said.

‘No, but Paul did. He told me.’ A short silence ensued.

‘So, how long have you been in Hungary?’ came the inevitable question.

I outlined our preceding seven years as briefly as I could. Éva, who had been a number of times to England, was more incredulous than most that we could enjoy living in Hungary.

Our conversation turned to the group I would teach. There was Éva’s sister-in-law, a consultant radiologist, and her artist husband, Pista. There was another married couple, both consultants, and a woman who was a medical secretary at the main accident hospital. Although all now in their fifties, they had known each other since their student days. They had all passed the advanced state exam in English, but both for work and pleasure wanted to have lessons again.

I went on to ask Éva about our other neighbours in the flat next to hers.

‘Oh, they’re from Transylvania,’ she said. ‘I’m not sure what they do, but they work long hours. We’ve said hallo once or twice when we’ve met in the lift, but I don’t know much more about them. I can’t imagine how they all managed to get out of Romania - you know, they never let a whole family out of the country together.’

‘What about the flat next to ours - has it been empty long?’

‘That flat’s always been rented out, just like yours,’ she said, ‘but I think there are new people moving in quite soon.’

I glanced at the clock. It was late. I should go and sleep while I could. We agreed to hold the first lesson the following week. Éva bade me goodnight and left me once again in the gloomy corridor, now considerably quieter. As I fumbled for my keys I thought I glimpsed a quick movement on the floor beneath Éva’s plants by the window, but peering more closely I saw nothing, and thought no more of it.

Click here for earlier extracts

Main photo: The Margaret Island - Courtesy Fortepan/ Fortepan

LATEST NEWS IN community & culture