An Englishwoman's Life in Communist Hungary': Book 2, Chapter 2.

- 18 Oct 2023 11:51 AM

Now You See It, Now You Don’t and House of Cards have been included as part of the Open Society Archive dedicated to this period in the CEU. You can read a serialisation of them here on Xpatloop. You can also buy the dual-volume book on Kindle as well as in Stanfords London.

Book Two, Chapter two: First Cracks

Part 3 – More new neighbours; Ceauşescu’s arrest

In the days that followed, Éva’s prediction was fulfilled. A family from Libya moved in next door to us. A large number of people were involved in the process, and it was thus difficult to determine exactly which of them would be living there.

At around the same time, a sofa we had ordered from a shop in town was delivered. It had a wooden frame and was rather heavy, but we had happily told them we had a lift. The two men carried it from the van up the three steps into the building, after the caretaker had unbolted an adjoining glass door so they could get through. He was covered in an ashen powder - he had been wheeling the bins out of the area at the lower end of the rubbish chute when the men had arrived. He scratched his dusty head.

‘Don’t think you’ll get that in the lift,’ he said. This eventuality had not occurred to us. ‘Try turning it on its end,’ he suggested as we approached the lift doors. He went ahead and held the lift door open. The men heaved it onto one end and inched it forwards. One or two people, seemingly in no hurry either to leave or get home, stood around watching, urging and encouraging.

‘Try it round the other way,’ said one.

‘Yes, that’s it!’ said another.

‘No way,’ commented a third. It soon became obvious to all there assembled that indeed, there was no possibility that this sofa could be squeezed into the lift.

‘What floor you on?’ asked one of the movers.

‘Ninth,’ Paul grimaced, fearing the worst. Silence. ‘What are you going to do?’ he asked finally. The first man put a cigarette to his lips and looking Paul straight in the eye replied, ‘That all depends on what you recommend.’

His meaning was not lost on us. ‘Five hundred forints?’ The men exchanged glances, then nodded.

An old 500-forint note

As I opened the door to our corridor, intending to make ready the customary bottles of beer, I was met by our new Libyan neighbours making for the lift. The man, seemingly aware of which flat I lived in and of my nationality, greeted me in English. ‘Hallo, I’m Suli. This is my family,’ he said, indicating his beaming wife and five children. ‘Do you know where we can buy lamb meat?’ he continued.

I smiled to myself, thinking back to the only time in seven years I had eaten lamb in Budapest, and how I had procured it. I had had a friendly dispute with a student who worked for the Hungarian Meat Trust. He insisted that lamb could be bought all over the city, though I had never seen it for sale anywhere. A few evenings later he knocked on the door of my classroom and presented me with a bag containing half a lamb – seven kilos of meat.

‘No, I’m sorry,’ I told Suli. Seemingly unperturbed he said, ‘These are my children,’ nodding towards them. ‘You have children?’

‘Yes, two,’ I replied.

‘You come see us,’ he said, leading his family to the lift. ‘Bye bye!’ The children looked shyly as they walked past me. I went on to our front door wondering how seven people could possibly squeeze themselves into fifty-something square metres.

*

My evenings of teaching at Lingua were now regular and usually followed by a meeting with Miklós, a meal and more talks about America. My days were spent with the children, the mornings on the Margaret Island, the afternoons at home. The weather was becoming noticeably colder and the wind howled around the top of our building: there was a veritable wind tunnel between ours and the next block of flats. The ill-fitting windows were draughty, though much more so on Éva’s side which faced the hills and the Danube.

Some days before Christmas, taking the children with us, we went to get our Christmas tree. The first snow had already fallen, dry and powdery, the wind whipping it up in clouds. A Christmas market had opened in a large deserted area in front of Árpád híd, at the intersection of Váci út and Robert Károly körút, where coloured light bulbs strung to a long cable danced in the gusts of wind and cast strange shadows on the snow.

There was an abundance of trees and it was not difficult to find one we liked. It was trussed up with string, and with John ceremoniously clinging to one of its branches, and Hannah in the backpack, we trudged the well-trodden snow path towards home.

Suddenly someone called out from behind us. ‘Paul! Marion!’ We turned to see our old neighbour Laci from the Dózsa György út flat with a small tree under his arm.

‘What are you doing here?’ he asked. It seemed a strange question as he and Cili had already visited us in our new home, and since both he and Paul had a Christmas tree in their hands.

‘We’ve just bought our tree,’ Paul began.

‘But don’t you know what’s happening? Haven’t you heard?’ Laci interrupted. ‘They’ve got Ceausescu! It’s live on TV! You can see it as it’s happening - go home and put the TV on!’

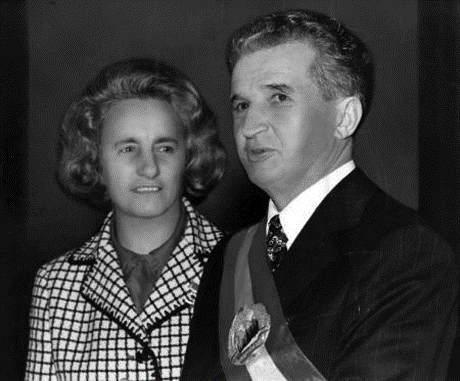

Nicolae Ceaucescu and his wife, Elena

Wishing him a hurried happy Christmas, we headed for our flat. We left the tree out in the corridor and pulled off our snowy boots, but with coats still on walked into the room and put on the television.

A faltering Hungarian commentary accompanied jerky pictures of some people crouching in the corridor of what we were told was the Romanian TV building. They were making their way to a studio further along the corridor where their colleagues were updating their Romanian compatriots on the current state of affairs in the country.

The Hungarian commentary was a rapid translation of the Romanian dialogue. Suddenly, there came the sound of shots being fired. ‘They’re shooting! They’re shooting!’ A black screen. Then, in the dark, ‘We don’t know how long we can keep broadcasting.’ There followed a quick summary from Hungarian television of the main happenings of the day, the beginnings of what seemed to be a revolution in Timisoara (Temesvár), which was then interrupted by more live pictures. ‘.....and Ceausescu and his wife are being held following their arrest earlier today,’ continued the broadcast.

The Trianon Treaty of 1920, which reduced Hungary’s territory to a mere third of its original size, had resulted in two million Hungarians finding themselves inhabitants of Romania. It was a situation neither they nor the citizens of Hungary could easily accept, and these Transylvanians continued to use the Hungarian language in those areas where they lived. This explained the particular interest that events in Romania held for Hungarians, many of whom had relatives or other contacts there.

‘We ought to go and congratulate our neighbours!’ I said to Paul. He was doubtful. ‘No, come on,’ I said, quite infected with the excitement and the drama of what we had just witnessed. ‘Let’s take that bottle of cognac we bought for Christmas and go and celebrate with them!’

Hesitatingly, Paul went for the bottle while I found a tray and four glasses. ‘Come on!’ I said, picking Hannah up off the floor and beckoning to John. Though there had been no such violence or drama in Hungary’s end to Communism just some months previously, the feeling of déja-vu was inescapable, as was the exhilaration of witnessing an historical event on our doorstep.

I knocked timidly - maybe they would find our desire to share this moment intrusive. The door opened. I stood, tray in hand, John clutching my leg and Paul to one side holding Hannah.

‘We came to congratulate you - you know, don’t you, they’ve got Ceausescu?’

‘Come in, come in,’ they said eagerly, leading us into their sitting room, where inevitably the television was also tuned in to the live broadcast.

Grainy TV pictures of the arrested couple

The following hours passed in mutual questioning and abridged autobiographies. We learnt that Feri made and flew model aeroplanes. He had been given a passport some years previously to come to Budapest for a flying competition late in August. Although as Éva had rightly said, the authorities never granted passports simultaneously to all the members of one family, Feri’s wife Évi, a seamstress, decided to try her luck and apply for a visa to visit an uncle in Budapest.

One advantage of a cumbersome bureaucracy was the virtual inevitability of important oversights not occurring. She was lucky. Évi and their then six-year-old son Robi were granted exit visas coinciding with Feri’s competition dates. Preparations were made in total secrecy; even best friends could not be trusted when it came to a planned defection.

But then disaster struck: the authorities informed Évi that although she was free to travel, Robi must remain at home as he would be obliged to start school at the end of August.

They had wrestled with the problem for days, knowing that such an opportunity was unlikely to repeat itself, and they resigned themselves to leaving Robi with Feri’s parents in the hope they could later persuade the Romanian authorities to allow him to follow them. With tears in her eyes Évi described her departure, the six months of battling to be reunited with Robi, and their emotional meeting on the border after permission had finally been granted.

Click here for earlier extracts

Main photo: Lifts in an old ‘panel’ block of flats

LATEST NEWS IN community & culture