An Englishwoman's Life in Communist Hungary': Book 2, Chapter 4.

- 5 Mar 2024 4:00 PM

Now You See It, Now You Don’t and House of Cards have been included as part of the Open Society Archive dedicated to this period in the CEU. You can read a serialisation of them here on Xpatloop. You can also buy the dual-volume book on Kindle as well as in Stanfords London.

Book 2, Chapter 4

Part 3 – Neighbourly relations; Gundel teaching

We felt very much at home here, not just in the flat itself but in the area to which it belonged. There were nine apartments in the house in all – six large ones in the main body of the building, a small one in the attic and two somewhat larger ones in the windowed basement.

On the ground floor lived spinster twins, well into their sixties. This flat had been their parents’ and now they lived alone, still working part-time, but spending increasing amounts of time tending the garden – it was one of these sisters we had seen on our first visit.

Opposite them lived the Hortobágyi-s, a couple in their fifties, with their already grown-up son and daughter. Above the twins lived a young couple, the Szabó-s, whom I had only seen from the window, smartly dressed, on their way to and from work. Next to them and beneath us were Mr. and Mrs. Kis, in their early sixties.

We had heard that Mrs. Kis’s father had apparently had the house built in the twenties or thirties. Our immediate neighbours were also in their sixties, the Katona-s, who had assisted in witnessing the documents and counting the money when we had paid for the flat.

Above them lived a Mrs. Sándor in a tiny flat which straddled the stairwell and overlapped their and our sitting room ceilings by a few feet. One of the basement dwellings was occupied by a single man rarely seen by anyone, while the other was empty – the previous tenant was now in prison, though no-one seemed entirely certain what his crime had been.

Although this was by far the most middle-class house we had yet lived in, there were problems here too, caused in part by the fact that the owners of four of the apartments had lived here for more than thirty years and knew every detail of the others’ lives, their family problems and political loyalties.

As newcomers we were regarded as potential allies by each and were made privy to secrets and grievances deemed sufficiently shocking to secure our sympathies and support.

‘No, we never speak to Mrs. Sándor,’ Mr. Katona told me. ‘She was in the ÁVÓ, the state secret police in the fifties, an informant. She’s a terrible woman. Don’t believe anything she tells you. And Mrs. Kis,’ he whispered - ‘Jewish,’ nodding as though to confirm some unspoken understanding between us.

Thus Mrs. Sándor: ‘Huh, the Katona-s! Just because they’ve got a large flat they think they can lord it over us all. Who do they think they are? I never go to residents’ meetings – if they need something mended they always get the money; when the rain was pouring through the roof on me in bed they said I would have to wait for a residents’ meeting to vote on whether I could have any money from the house fund for the repairs. Huh!’

Meanwhile, Mrs. Kis, whether from affectation or a genuine vestige of a wealthier and more genteel past, saw it as her duty to maintain the social standing of the house in the neighbourhood.

‘We don’t hang our washing out like the Italians,’ she said with evident condescension and distaste, when following my first swimming expedition with the children I had hung our towels on the balcony to dry. Also, on August 20th, St. Stephen’s Day and a national holiday, she came up to complain that we had not hung out the national flag by the front door to the house.

Ágota and Henrietta maintained good relations with everyone, partly due to their understanding natures and a wish for a peaceful atmosphere, and partly out of a fear of incurring others’ displeasure or censure, though this did not make them immune to criticism.

‘We ought to raise the amount we pay into the house fund,’ Edina Szabó, an economist, had stated when we first discussed matters pertaining to the upkeep of the building. ‘I know that Ágota and Henrietta couldn’t pay, but then they can move – why do they need such a big flat anyway?’

As pure logic this was undeniable, but the sisters had not voted for the change which had brought soaring gas and electricity prices in its wake, and were obviously hopeful of living out their days in what had been the family home for half a century. In the event, Henrietta died soon after, and the cessation of her contribution to household expenses placed a heavy burden on Ágota.

‘It’s difficult for Ágota,’ said Mrs. Hortobágyi. ‘It’s hard for us too – I haven’t been able to work, what with my heart problem, and we’ve got the children. It’s all right for the Szabó-s to talk, they’re business people…. I do wish Mrs. Kis would allow us to cut that bottom branch off the acacia, it makes our sitting room so dark…’

And so it was that each had their grievances against the other, while on certain questions alliances were formed for no apparently logical reason. Mrs. Sándor alone seemed to isolate herself totally from the other residents, we appeared to be the only people with whom she was on speaking terms.

Though Paul still taught at the Music Academy, I had left Lingua. Increasingly, courses were run for businesses, and the majority of them were early in the morning or in the evening – times I wanted to be at home. John started nursery in the autumn after we had moved to Zugló – I dreaded it, knowing that a combination of being over-sensitive and clinging, together with his not having more than a word or two of Hungarian, would make it a traumatic experience.

If anything, I underestimated the assault on our nerves that the first weeks and months at nursery would inflict. In spite of the tireless efforts of the staff to make him feel at home, their patience and kindness, John had to be peeled off me every morning, a screaming, desperate bundle of flailing limbs, choking sobs and accusatory glances.

Each morning I awoke with a knotted stomach and a guilty conscience, forced to battle against the easy option of keeping him at home.

Yet he was four and half – in England he could well have been starting school – and I knew it would not be easier were I to postpone for a year his transition from home to the outside world.

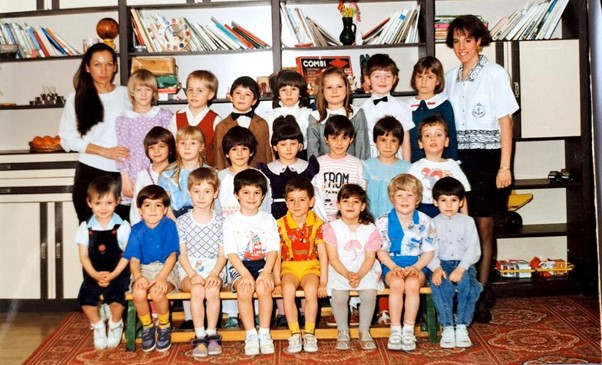

John’s nursery class

Soon we discovered that if Paul took him it was somewhat less distressing. John stayed only until lunchtime, whereas the majority of children then slept there, played, ate tea and were collected by their parents at four or five o’clock.

Although I did no regular work other than teaching Éva’s group, I was still approached to undertake editing, translation revisions and recordings. One such recording was to accompany a children’s English course book, and it was to be done in a film studios a mere five minutes’ walk from our house.

After completing the work we all walked out into the leafy compound surrounding the studio, and towards the gate. Suddenly I stopped still in amazement – coming towards us was Michael York in the company of the film director and producer I had worked with the previous summer. Certain that they would not recall our meeting, I made to walk past them.

‘Marion!’ called the producer. ‘Don’t you remember us?’

‘Of course I do,’ I said.

‘We couldn’t come in October because of the taxi blockade, and then in January we tried to ring you but no-one was ever in.’

‘I know, I saw you on Studio on television, but we’d moved – we live just down the road here. I’ve been recording some language-teaching cassettes.’

They seemed excited about their new film which they were taking to the Berlin film festival, though I heard subsequently that it failed to make an impression.

I had been asked if I would be interested in teaching at the Gundel restaurant. Following its era in the hands of the state, it had recently been bought for a rumoured several million dollars by the New York restaurateur George Lang.

The premises would be closed for several months, during which time it had been decreed that all staff would be required to learn English. I had taught engineers and doctors, office and factory workers, journalists and nursery school children, but never waiters, and not in a restaurant: I agreed.

I was handed a list with ten names: nine men and one woman. I was led to what looked like a red plush boardroom. Nine chairs were occupied. I read out the list of names until I was informed by the others of the absence of the man called Karcsi.

‘He’ll be here in a minute,’ they said.

As I began to explain the course content the door opened and Karcsi made his entrance: middle-aged, strongly built, with a beaming smile behind his handlebar moustache. He stared at me.

‘I know you!’ he said in Hungarian. ‘But where from?’

I knew but did not help him.

‘You’re so familiar…’ The rest of the group was enjoying this unexpected start to their lesson.

‘Yes! I know. You used to walk past the restaurant every day with your children!’

And so it was. Though we had never spoken to each other, my daily route for two years from the Dózsa György flat into the park took me by the lake on the opposite side of the road to the Gundel. Every day we would see the moustached doorman standing outside the restaurant, and after a time we would wave in greeting. Of course it now came as a surprise to him to learn that I was not only his English teacher but actually English too.

Lessons were varied and interesting – not only did I have to learn every utensil and culinary term in Hungarian, but the venue for our lessons changed each week as building and decorating work progressed. The waiters were a lively bunch, always guaranteed to try and cheat in tests, whose results were required by the management.

They were also outspoken in their views of the changes being made to the restaurant, their regular complaint of low wages predominating. With pride they showed me the wood from Spain to make the pillars in the main dining room, the Irish linen and the Zsolnay porcelain.

It was only after the first week’s teaching that I realized that George Lang was in fact none other than Láng György, whose fascinating cookery book I had once been given by Danielle. Many pages were devoted to a eulogy for the Gundel at a time when Lang himself could not have dreamt he would one day own it. I told the story to Éva’s group the same week.

‘And didn’t you see that all the illustrations in the book are by Pista?’ laughed Erzsi, his wife. I had not, but they were.

‘Yes, that was in the good old days,’ smiled Pista ruefully.

George Lang cookery book illustrated by my student, István Engel-Teván

Click here for earlier extracts

Main photo: Our local tram

LATEST NEWS IN community & culture