Xpat Opinion: The Unbearable Loneliness of Human Beings

- 19 Sep 2022 12:49 PM

“Perhaps it is partly that she has always been there, a changeless human reference point in British life,” Boris Johnson said. “The person who, all the surveys say, appears most often in our dreams. So unvarying in her pole-star radiance that we have perhaps been lulled into thinking that she might be in some way eternal.”

The British people have lost the symbol of national immortality. Like the Hungarians, the Bristish created a monarchy over a thousand years ago to give them the hope or illusion that their lives have meaning, that something permanent will outlast the decay and disappearance of their bodies. With the passing of Queen Elizabeth, the British people’s collective immortality is diminished.

Death comes even to those believed to be immortal. What greater evil is there than that imposed on us, against our will, by the Grim Reaper? We seek to protect our immortality, said psychoanalyst Otto Rank, rather than our lives.

Islamic suicide bombers have long proven that preserving their illusion of immortality is more important than preserving their bodies. Throughout the ages, the British monarchy has been the most powerful symbol of the British people’s denial of death.

The denial of death, proposes Ernest Becker in Escape from Evil, is “an expression of the will to live, the burning desire of the creature to count, to make a difference on the planet because he has emerged on it, and has worked, suffered, and died.”

The basic motive of mankind, said Otto Rank, is self-perpetuation, reaching towards the dream of immortality, an immortality provided by the seductive blandishments of religion and the nation-state.

Today, like religion, the nation-state is a universal symbol of immortality. Each of the 193 member-states of the United Nations, including Hungary, promises permanent safety, meaning and dignity for its citizens--particles of cosmic dust huddled together on a tiny portion of a minuscule planet in a vast, unfathomable, frightening cosmos that cares nothing for human beings. The earth itself is a lonely outpost of life in the blackness of space.

For any understanding of the universal loneliness of human beings, isn’t the strange consciousness of living—the dim awareness that we're alive, for a moment, on a speck of dust as it spins, meaninglessly, around the sun, itself only a slightly larger speck of dust in the vast, incomprehensible spaces of the cosmos—the single most significant fact of human existence?

Unlike Hungary, the British government has created the post of Minister of Loneliness. In June 2021, during the U.K.’s annual "Loneliness Awareness Week," Diana Barran, the Minister of Loneliness, warned that the U.K. was in a "critical stage" of tackling loneliness. “Many of those who felt lonely before the pandemic,” added the Loneliness Minister, “will continue to do so as lockdown restrictions are eased." She urged "everyone who may be feeling lonely, or isolated to reach out to someone, and if they know someone who they feel might be lonely, or isolated, to get in touch."

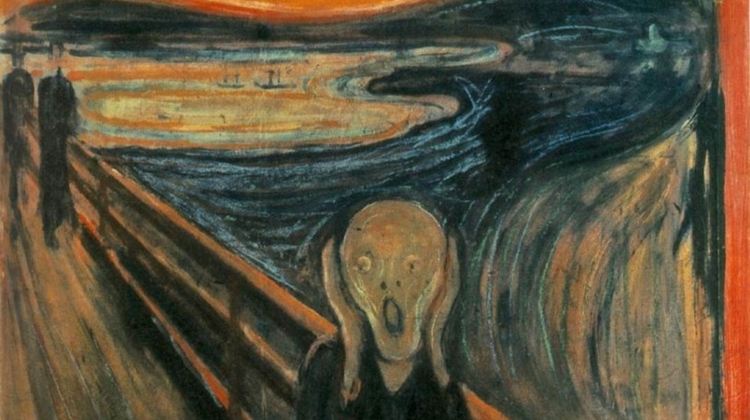

The universal loneliness of human beings is portrayed unforgettably in Edvard Munch’s late 19th century masterpiece The Scream, a shattering portrayal of the anxiety of loneliness -- an anxiety shared by all self-conscious mortals, said Otto Rank, to one extent or another.

In a January 1892 diary entry, Munch described his inspiration for the image - please see above:

One evening I was walking along a path, the city was on one side and the fjord below. I felt tired and ill. I stopped and looked out over the fjord – the sun was setting, and the clouds turning blood red. I sensed a scream passing through nature; it seemed to me that I heard the scream. I painted this picture, painted the clouds as actual blood. The color shrieked. This became The Scream.

Whether we’re expats or not, we’re all lonely wherever we live on the planet Earth. No matter how much science unravels the secrets of biology, chemistry, physics or the brain, it doesn’t have a single word to say about what it means for a person to be alive, to be conscious, a speck of dust, on the planet Earth, the only planet in the cosmos teeming with life, which makes it the loneliest of all the trillions and trillions of planets in the cosmos.

Life is an infinetisimal moment of light, a holiday on Earth, sandwiched between two eternities of silence. What do we know of the two oblivions that engulf the human being, mirroring each other so eerily? Nothing. “For after all, what is man in nature,” wondered Pascal in 1670. “A nothing in comparison with the infinite, an absolute in comparison with nothing, a central point between nothing and all … He is equally incapable of seeing the nothingness from which he came, and the infinite in which he is engulfed.”

Awestruck at finding himself alive for a moment on the planet Earth, Pascal asked: “When I consider the short extent of my life, swallowed up in the eternity before and after, the small space that I fill or even see, engulfed in the infinite immensity of spaces unknown to me and which know me not, I am terrified and astounded … Who put me here?”

In 1842, the eternally lonely Kierkegaard wondered: "Who am I? How did I come into the world? Why was I not consulted? … And if I am to be compelled to take part in it, where is the director? I should like to make a remark to him. Is there no director? Whither shall I turn with my complaint? … How did it come about that I became guilty: Or am I not guilty? Why am I so called in all human tongues?"

The nature of consciousness remains utterly mysterious. Neuroscientists cannot even agree on a definition of consciousness, or on a definition of a “self” that is conscious, much less measure either one. According to philosopher David Chalmers, we cannot explain how the water of the brain turns into the wine of consciousness. No scientific instrument has ever been invented to detect the presence or absence of consciousness.

What Otto Rank called the “consciousness of living” (a term he coined) is identical, I believe, to the “hard problem” of consciousness, which requires explaining how the first-person, universally lonely experience of “I am” emerged in the cosmos. No one has a clue.

But when the protective shield of culture cracks open, as it does during disasters like Covid and the death of Queen Elizabeth, and we can no longer deny death, the terror of falling into the abyss suddenly overwhelms us with dread. "This is the terror," writes Ernest Becker in The Denial of Death, "to have emerged from nothing, to have a name, consciousness of self, deep inner feelings, an excruciating yearning for life and self-expression--and with all this yet to die" -- to return to the void of non-being, of nothingness, from which we all emerged. All human beings die alone. No one can die your death except you.

And so when Queen Elizabeth died, another gaping hole opened in the British psyche, already traumatized by Brexit, Covid and the long-term decline of what was once called the “British Empire.”

Mortal, lonely people on a tiny island in the Atlantic Ocean that gave itself the name “Great Britain” are mourning the prospect of their own deaths—which, at least for a few more days, they can no longer deny - not the death of their immortal Queen.

By Robert Kramer, PhD

Professor of Psychoanalysis

Eötvös Loránd University Hungary

LATEST NEWS IN specials