An Englishwoman's Life in Communist Hungary': Book 2, Chapter 2.

- 17 Nov 2023 8:49 AM

Now You See It, Now You Don’t and House of Cards have been included as part of the Open Society Archive dedicated to this period in the CEU. You can read a serialisation of them here on Xpatloop. You can also buy the dual-volume book on Kindle as well as in Stanfords London.

Book Two, Chapter two: First Cracks

Part 4 – Christmas; visit to Virginia

There was a knock at the door. Feri got up to answer it, while I suddenly wondered where the children had disappeared to. I also got up and saw Feri hold the front door wide open revealing Éva and a figure in the dark behind her.

‘I thought I heard Paul’s laugh,’ she said, coming in and simultaneously shaking hands with Feri. ‘A friend of yours was looking for you.’

Éva stepped forwards to introduce herself to Évi, while the short, stocky figure in the corridor moved into the light. It was Attila. Attila, who in 1956 at the age of sixteen had decided there was no future for him under communism, and then cycled over the border to Austria at the start of the Hungarian revolution. Attila, who had travelled on to England and finally returned to live in Hungary in 1983.

‘Marion, Paul!’ he shouted, coming into the room, ‘I’ve been ringing the bell for ages, I thought I’d never get a cup of tea!’ It was a standing joke that Attila drank more and stronger tea than most English people we knew. Évi and Feri produced two more cognac glasses and we sat down again in the sparsely furnished room talking all at once against a background of children’s laughter from the adjacent room, and the continuing news broadcast from Romania. We explained to Attila how we came to be in Feri and Évi’s flat and they in turn repeated their story of how they had left Romania.

‘Well, I’m leaving for Transylvania tomorrow!’ Attila announced.

‘What? You’re crazy! You’re not really, are you?’ we burst out.

‘Of course I am,’ retorted Attila. ‘I filled the car up today with the things I want to take - newspapers, books, oranges, sausages, chocolate.....’ he tailed off, looking serious. ‘Look, if I’m not back in three days ring the British embassy and tell them I’m missing. I’m coming back in three days, I’ll ring you as soon as I’m home.’

I admired Attila’s implicit trust in the British diplomatic service. On the one occasion, in 1978, when we had first visited Hungary and been on the verge of arrest, I had rung the embassy for help. They politely informed me that they were closed on Saturday mornings and could not assist. Aside from this, we were now in our sixth flat since coming to live in Budapest in 1982, and in spite of registering every change of address with them – this was compulsory – their letters were still being sent to our first address.

It was getting late. ‘I’ll have to go,’ said Attila. ‘I just wanted to ask you to do me this favour – you should hear from me on Friday when I get home.’ He duly shook hands with Éva and a bemused Feri and Évi, and left. Éva also made to leave and I went to Robi’s room to find him still playing with John – Hannah was already asleep on Robi’s bed.

‘Thank you so much for coming,’ said Évi, handing me back the tray and glasses. ‘I hope your friend will be all right,’ added Feri.

‘He’s crazy,’ I said, shrugging. ‘We’ll let you know when he gets back.’

News broadcasts in the days following included footage of the summary trial and execution of Nicolae Ceausescu and his wife. Attila dropped in on the Friday afternoon, proudly clutching two empty shells from bullets fired close to his car.

Ceaucescu and Elena were executed by firing squad

‘I’m leaving again the day after tomorrow,’ he said in his customary excited manner. ‘I should be back on Tuesday; tomorrow I’ll go and get more newspapers and food to take. I met the crew from BBC’s Newsnight programme, they did an interview with me on the street there. Maybe I’ll be able to show you later, they said they’d send me a video. So, if you don’t hear anything by Tuesday night, ring the embassy.’ And with those words he was gone.

Meanwhile it was Christmas. Attila had already brought us a parcel from my mother in the autumn, which included a Christmas pudding and the wherewithal to make a Christmas cake. My final lesson at Lingua had included mulled wine boiled on the hotplate of the small kitchen on the sixth floor and carried to our classroom on ground level, and my students’ initiation into such games as Charades.

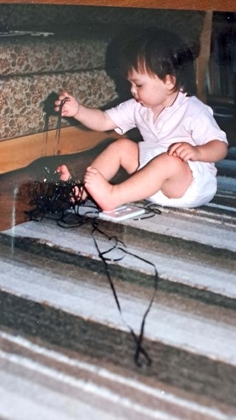

At Éva’s we had Earl Grey and a variety of biscuits and cakes brought by the group, together with Éva’s own speciality of candied orange peel and nuts. It was Hannah’s first Christmas, but she was happiest of all sitting in a heap of torn wrapping paper and ribbons or, when unobserved, deftly extracting yards of tape from the cassettes she had by now discovered on the shelf. John, at two and a half, was entranced by the Christmas tree lights, the candles and his new tricycle.

It took a while before he became proficient at anything but pedalling backwards, but Robi was delighted to spend his school holiday pushing his new-found playmate up and down the long corridor.

Caught in the act!

Between Christmas and New Year, we received a telegram from our friends Virginia and József, both Church ministers, inviting us to see them. They lived, without a phone, in Dabas, about an hour’s drive from Budapest.

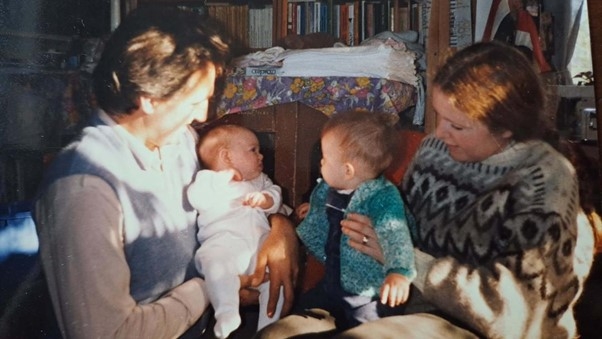

Virginia had arrived in Hungary some six months after us, newly married to József. They had met at theological college in Chicago, he having travelled from his home town of Dabas, she from California. They had been given our address by an English friend of ours who had left England for the Chicago college on the same day as we had set out eastwards for Budapest. Virginia and József’s first child, Flora, had been born just five months after Hannah.

Since our first meeting in 1983, we had seen each other regularly, usually in their sprawling rectory. This hundred-year-old house, with its thick wattle and daub walls, was set in a huge plot of land, a scrubby wilderness of walnut trees and fruit bushes, of dilapidated outbuildings and dusty weeds.

The single-storey house had a large verandah at the front, completely overgrown with grapevines and ivy, and from the first warm days of spring to the last glow of autumn, we would sit in its shade, eating whatever József’s parishioners had brought them. In winter they received the spoils of pig killings, in summer every kind of fruit and vegetable. Their income was low but there was never any shortage of food.

We arrived in the late morning of a bleak January day. Our car skidded through the broken wooden gates of their garden. Snow lay in white clumps on the vine leaves above the verandah and long icicles hung from the eaves. We let ourselves in through the front door, calling to Virginia. She appeared from the gloomy kitchen, a mop of dark curls and blue, twinkling eyes.

‘I’m so glad you could come,’ she said in her soft California drawl. ‘Come and have some tea, I’ve just put the kettle on.’

We followed her back into the kitchen, glad to be in the warm.

‘How’s Flora?’ I asked.

‘She has a cold,’ replied Virginia, pouring the tea, ‘and she’s still waking up nights. I don’t know how you managed with John,’ she added.

‘It was awful,’ I said.

‘I’d like to try leaving Flora a night or two and see if she learns to sleep through, but József won’t hear of it.’

As if on cue, József came into the kitchen from the garden, smiling warmly.

‘Marion! Paul!’ he said, kissing me, and shaking Paul vigorously by the hand. ‘Oh sorry,’ he added, seeing Hannah asleep in my lap.

‘It’s all right,’ I said. ‘I don’t want her to sleep all day or she’ll be up tonight.’

‘Huh,’ József grunted, ‘Virginia would only be happy if Flora slept twenty-four hours a day. And how’s John?’ he asked us, changing the subject and walking over to the high chair where he was happily munching a biscuit.

‘Hannah sleep,’ said John, pointing a sticky finger in her direction.

Far in the distance, at the other end of the house, came a wail that announced Flora had awoken.

József with Flóra, me with Hannah

‘I’ll go,’ said József, making for the door. He soon returned with her and set about making her food and drink. Then, sitting back at the table with Flora in his lap, he began to feed her.

‘Has Virginia told you about the house?’ he said.

‘No, what house?’ Paul asked.

‘The Church has decided to start building a new rectory,’ Virginia said, ‘this house is gradually subsiding.’

‘How do you know?’ I asked in surprise.

‘I’ll show you,’ she said, opening the door into the hall. ‘Come and see.’

We followed Virginia out into the large, cold hall where we had first come in. At the far end was a door that led into the two bedrooms. Opposite the front door was one leading into what they called the Congregation Room. Church meetings were held in here, an echoing, bare-boarded hall with wooden chairs, and a tinny, out-of-tune piano in the corner.

Against the back wall were the many packing boxes full of Virginia’s books and other possessions she had still not found a place for. It was almost as cold here as outside, and I quickly took Hannah to a sofa in the hall where it was marginally warmer. By the time I returned Virginia was already pointing to a long crevice in the rear wall.

‘This has been getting wider for the last year, and new cracks have appeared under the windows,’ she said. ‘There are a couple in the children’s bedroom too, so we had them looked at, and they say we’ll have to leave sooner or later.’

‘Where will the new rectory be?’ asked Paul.

‘There,’ said Virginia, pointing to a similarly dilapidated building across the other side of the garden. ‘That’s in a terrible state and it also belongs to the Church. They’ll pull it down and build us a new house in its place.’ She looked wistful. ‘I know there are lots of problems here, but I’ll miss this house. I’ve been here ever since I got married to József and came to live in Hungary....’

LATEST NEWS IN community & culture