An Englishwoman's Life in Communist Hungary': Book 2, Chapter 3.

- 30 Jan 2024 2:32 PM

Now You See It, Now You Don’t and House of Cards have been included as part of the Open Society Archive dedicated to this period in the CEU. You can read a serialisation of them here on Xpatloop. You can also buy the dual-volume book on Kindle as well as in Stanfords London.

Book 2, chapter three: Neighbours

Part 6 – Taxis blockade Budapest’s bridges and Hungary’s borders

Tamás’s doctor brother came to see us to collect the final month’s rent and to say goodbye. He was not surprised that we had decided to make our home in Hungary.

‘Everything’s different now,’ he said. ‘You’ll see, Hungary will be just like Austria in a few years. Life will be better for everyone.’

October 23rd, the anniversary of the 1956 uprising, always referred to as a counter-revolution in communist times, was the final ghost to be laid. It had never been advisable to talk of it except in whispers among friends, and a tangible tension hung in the air every year as its anniversary approached.

But on this 23rd of October, walking home in the dark, I saw candles glowing forth from many windows of the blocks of flats. At first, I was mystified, but then I remembered the date. This was a first tentative step towards an official acknowledgement of a day that had changed the course of Hungary’s history and many of its citizens’ lives.

October was drawing to a close. The Ács-es could only move into their new flat in November as the building was still not completed. I had a telephone call from a film studio on the other side of town asking if I would do a voice-over.

I enjoyed such work and agreed. Since it was an evening job and likely to end late. I decided to drive. On my way to Moszkva tér I noticed long queues outside a petrol station. I realised that the price must be about to increase but I was not unduly worried – I had a full tank and hardly ever drove further than the Margaret Island.

The work went well, though the film was long and we realised it could well be midnight before we finished. I was sitting outside the small studio waiting for someone else to finish their part when a woman burst into the ante-room.

‘Do any of you live in Pest?’ she asked breathlessly.

‘Yes, I do,’ I said.

‘Then you’d better leave right now. The taxis are blockading the bridges because of the petrol price rise and you won’t be able to get home.’

As I gathered my belongings and made for the door she called after me, ‘We’ll ring you about when you can come and finish the recording.’

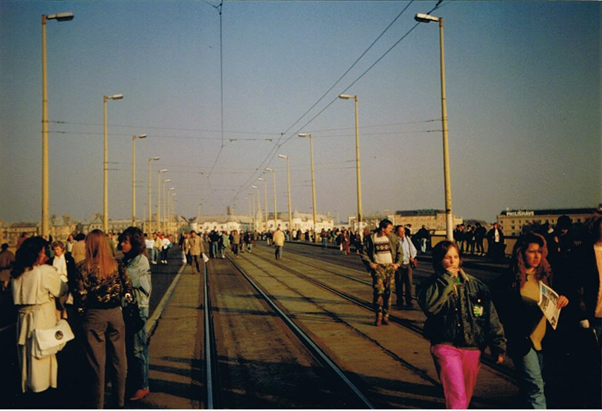

Pedestrians cross Budapest’s bridges on foot

The door slammed behind me as I ran to the car. I reasoned that the blockade would surely start with the most used bridges, Lánchíd, Margit híd, so if I drove up the river to Árpád híd I might still get across. As I neared the bridge a long queue stretched ahead of me. Cars had been abandoned on the pavement, their drivers obviously deciding to walk to the tram stop, or to cross the longest bridge in Budapest on foot. I sat in the unmoving line of vehicles trying to decide on the best course of action.

Suddenly the car in front accelerated noisily and shot out of the queue, over the pavement-like area separating road and tramway, thus avoiding the taxis that blocked the road itself, and along the tram lines towards the bridge. Without stopping to think, I followed him.

The car bumped over the concrete, then slid to left and right as the tyres failed to gain a hold of the tram lines, but I was on my way. Looking back in my rear-view mirror I saw some taxis move into position on the rails to prevent any other motorists following suit. However, I would not be able to leave the bridge on its blocked Pest side ahead, so I took a road leading from the middle of it and found my way home by another route.

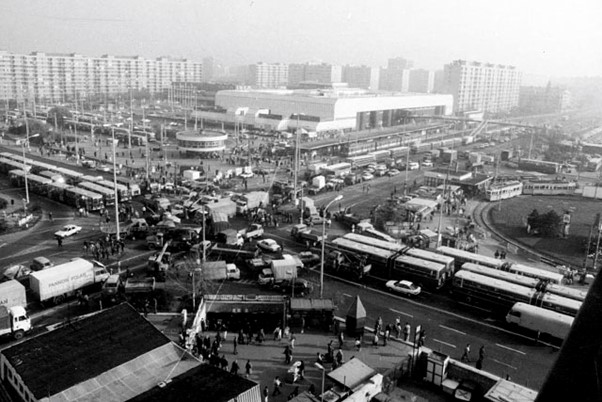

The whole country was brought to a standstill

The following day the whole country had been brought to a standstill. Taxis had blockaded every road border crossing from neighbouring countries as well as roads leading to and from the airport. People were obliged to walk across the bridges to get to work; many did not bother.

There was the unnatural silence of a city paralysed. Tense negotiations between government representatives and taxi drivers were broadcast live on television. Meanwhile, below our windows we could see the glow of a fire lit at the foot of Árpád híd where taxi drivers maintained their blockade and alternately spoke and argued with those who had opinions to voice.

Three days later compromises had been made and the virtual siege ended. Yet no doubt was left in anyone’s mind of the determination of ordinary people to now take an active role in the running of the country.

As the end of the year approached, we prepared for our move to Zugló. The Ács-es could only now move in December, thus we too would have to wait. The first snows came early, already in November, but melted again. Raw winds howled around the house, the bleak haunting sounds of winter.

As I stood at the bitterly cold Árpád híd tram stop after my evening’s teaching at Lingua, I thought back over the year: next door, Suli and his family had left – where to, no-one knew. The landlady came one day, and on learning from the man on the eighth floor that I had been his interpreter, invited us both in to share her horror at what she had found.

The bathroom stood an inch or two deep in water, towels lay soaking in the dirty pool, the glass shelf above the basin was broken. The kitchen was a mess of unwashed plates and food remnants on the floor, cutlery was missing, crockery broken.

Évi and Feri had already moved to their new home in Lövölde tér. Their flat now lay dark and silent. Éva, without whose help we would never have been able to buy our own flat, would inevitably miss us as surely as we would her.

To a small degree we had alleviated some of the loneliness of her first year without her husband; her friendship, meanwhile, had transformed our apprehension at living in a ‘panel’ flat into regret at having to leave. Though I would still teach her group, I could no longer cross the corridor at night and sit with her in her dressing-gown, drinking whatever she happened to find in the kitchen, nibbling whatever she had in the fridge, and talking late into the night.

Attila had visited us to say that he and his wife were now divorced. He had moved out to Zsámbék where he had bought a totally derelict house from a kindly alcoholic. He looked drawn and had started smoking again. Caroline was also in the throes of a separation, and I worried about Virginia.

The wind had died down. I shivered in the damp air. A yellow-grey fog was descending on the river, diffusing the dim lights of the city and obscuring the hills. I could just make out the building that housed Lingua on this side of the bridge, and the blocks where we lived on the other.

Looked at from where I now stood on this November night, nothing had visibly changed in the eight years since we had arrived in Budapest. Yet the lives of the people behind the façades had been altered irrevocably, and they remained in limbo between their safe pasts and their uncertain futures, between one bank of the river and its opposite side.

Click here for earlier extracts

Main photo: 1990 Taxi Blockade - Courtesy Fortepan/ Péter Záray

LATEST NEWS IN shopping