Xpat Opinion: The One Thing That All Electoral Systems Have In Common

- 11 Apr 2014 9:00 AM

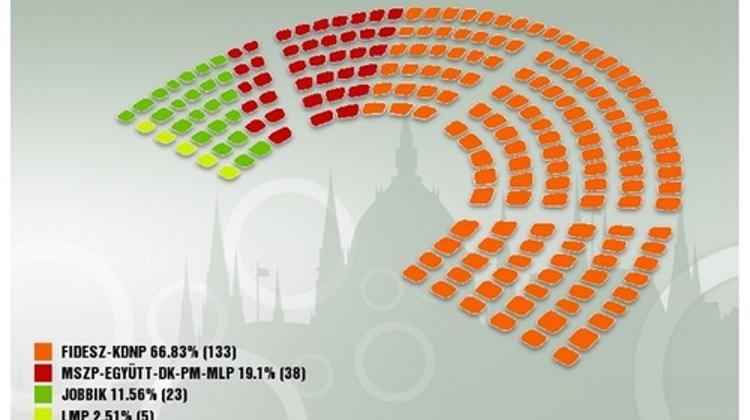

“Yesterday’s elections would have been won by Fidesz under any election system in the world,” wrote independent political analyst Gábor Török, as I mentioned previously. He’s not alone.

The Center for Fundamental Rights (CFR) just published a study about the electoral changes in Hungary (download here in English).

Here’s how they compare the Hungarian system to other systems:

There are many election systems in the world that benefit the winnerthe winner. In Greece, for example, the winning party automatically receives an additional 50 of the 300 parliamentary seats as a winner’s bonus. OSCE views the Greek system as fundamentally acceptable and worthy of support, as it enables the formation of stable governing majorities.

The 650 members of the British House of Commons are elected by simple majority. This solution allowed the winning party to take 63 percent of mandates while winning only 40.7 percent of the vote in 2001, taking 55 percent of the parliamentary mandates with 35.2 percent in 2004 and 47 percent of mandates with 36 percent of the vote in 2010.

These examples clearly show how an election result can “produce significant differences between the proportion of the popular vote received and the number of mandates won. At the same time, even major discrepancies of this kind are considered internationally acceptable practice and not objected to by either the OSCE or the Venice Commission, in favor of facilitating a majority and stable governance,” writes CFR, adding that the “Hungarian system traditionally favors a middle-of-the-road approach in which both majority elements and proportionality are represented.”

The results support CFR’s point. The winning Fidesz-KDNP alliance won (with 98.97 percent of votes counted) won 96 out of 106 districts. If it were the UK election system, Fidesz would have won bigger. If it were the German system, Fidesz would still have won. That’s what Prime Minister Orbán was talking about yesterday when he was questioned by a journalist whether the new system gives too much preference to the winner. Like every system, it has qualifications and it benefits the winner more than the former system. It was “a minor shift towards the majoritarian system,” as Századvég, a Hungarian think tank described the electoral reforms, but based on the same mixed system as before.

There are democratic election systems in the world which are more proportionate (like the German or Austrian system). There are democratic systems that are more majoritarian (the Anglo-Saxon systems). Somewhere between those two models stands the Hungarian system.

Some electoral systems reinforce government stability. Others place more emphasis on proportionality, balancing power between the government and the opposition. But all systems have one thing in common: To win, you have to win more votes in the constituencies and/or on the national list than your opponents. That’s what Fidesz did on Sunday. By a landslide. And that wasn’t because of the changes in the system. It was because that’s what the voters wanted.

By Ferenc Kumin

Source: A Blog About Hungary

This opinion does not necessarily represent the views of this portal. Your opinion articles are welcome too, for review before possible publication, via info@xpatloop.com

LATEST NEWS IN current affairs