An Englishwoman in Communist Hungary: Chapter 1, Part 1

- 20 Sep 2022 6:15 PM

Now You See It, Now You Don’t and House of Cards have been included as part of the Open Society Archive dedicated to this period in the CEU. You can read a serialisation of them here on Xpatloop. You can also buy the dual-volume book on Kindle as well as in Stanfords London.

CHAPTER ONE : Beginnings and Belongings: Vántus Károly utca

PART ONE

We had arrived. Rákóczi tér: a square with a huge covered market and stalls spilling on to the pavement, grubby children playing in a fenced-off area, old men engrossed in chess under straggling trees and, on the corner, two girls loitering and smoking - the regulars, who have made the name of Rákóczi tér synonymous with prostitution. A tram rattled past along the dusty boulevard (körút), a circular road which crosses the Danube by way of two bridges. Everything was hot, parched, dusty and noisy.

It seemed somehow appropriate that Miklós should have moved to this infamous square; Miklós, the great observer of people and life, our first friend in Hungary and the one ultimately responsible for our impulsive decision to leave England for a year or two to try our luck in Budapest.

Leaving our VW Beetle bulging with our belongings and the bags of fruit we had bought en route, we walked slowly across the road and into the dark, dirty stone entrance, past the black dustbins and rusty wall-mounted letter-boxes and on up the cool stairway.

We had to grope to find the iron banister; coming from the glare of the midday sun we could see nothing at all. Two flights up, a door led out onto an open walkway around the four sides of the courtyard.

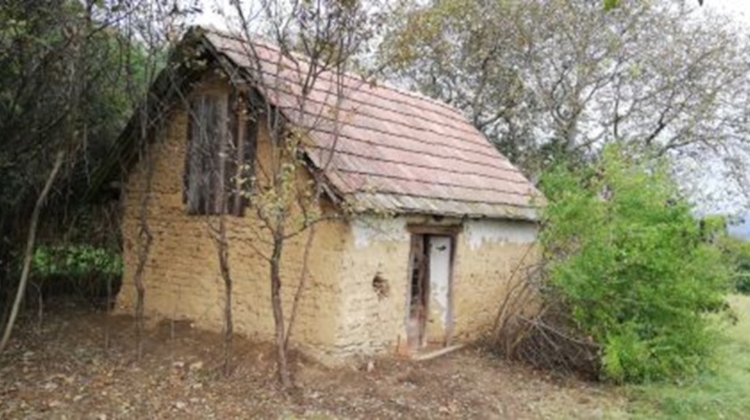

Most buildings are on this design, some of the courtyards having beautiful trees and flowers, even vines, but others are just dark, empty, concrete yards. What was most striking about this one was the mass of wooden scaffolding from ground to roof level, which Miklós later explained was all that prevented this crumbling block from collapsing.

Miklós’s building, Rákóczi tér

We rang the bell on the huge double doors, knowing that Miklós and his wife, Rézi, expected us sometime that afternoon. We were greeted with the customary kiss on both cheeks, much laughter and hugs. They led us into their spacious, airy flat which had twelve-foot high ceilings and parquet floors, in common with most old buildings.

We flopped on to the armchairs, inelegantly, with arms and legs spread to cool ourselves. The huge stained-glass windows overlooking the square formed an extraordinary mural of parrots and palm trees, bookcases reached almost to the ceiling on every wall and in a corner stood the traditional kályha, a tiled gas-fired stove, which would once have been wood-burning, some seven feet tall.

Magazines, newspapers, language textbooks (Miklós taught English and Rézi Russian), cigarette packets, coins and a bowl of fruit covered the small table, around which more papers and scribbled notes had fallen to the floor and over to the telephone by the wall adjoining the bedroom.

The Róth Miksa window

‘Welcome behind the iron curtain!’ Miklós smiled. ‘Now, what would you like to drink? Brandy, whisky?’

Rézi arrived from the kitchen with small cups of traditional, very strong, Hungarian coffee and glasses of cool soda water.

‘This is what I need,’ I said, gulping the soda water and helping myself to more.

‘It's so hot,’ Paul said. ‘What's the temperature?’

‘About thirty-eight degrees,’ said Rézi. ‘I just don't go out in the afternoons at all.’

The room, however, was shaded by the wooden blinds outside the windows, which cast a mellow light all around.

‘Come and have a look from the balcony,’ Miklós beckoned, picking up his lighter and putting another Marlboro to his lips as he headed for the adjoining room. This was similarly airy, and led out to an ornately carved stone balcony. There were two stools and a multitude of plants on the balcony, including a giant palm. Leaning over we could see, immediately below us, one of the girls we had noticed when we arrived. She was carefully counting a wad of 500 forint notes.

‘Well, if you have any financial problems,’ Miklós told Paul, ‘just send Marion here,’ and he winked at me.

The regulars have their papers checked by police: Courtesy Fortepan Magyar Rendőr

The chess players, mostly older men, sat on stone benches around stone tables, surrounded by small groups of silent onlookers, standing with hands clasped behind their backs.

The gypsy children shrieked in the fenced ball-game area and, in the middle of the road, a cat played lazily with a rag attached to a piece of string. It was too hot for me. I went back inside and chatted to Rézi about our travels through West and East Germany where, at the border, the officials had kept us for several hours and made us empty the car, before we could journey on to the wonderful town of Weimar, and thence to Prague and Budapest.

Whilst in East Germany we had been stopped five times by the police. It had been our first visit there and to Czechoslovakia, and the oppressive atmosphere and the belligerence of officials had made us begin to wonder if we had made a serious error of judgment in coming to stay in Budapest.

We had not mentioned our concern to each other, and it was dispelled completely as we crossed into Hungary, waved on by smiling border guards who did not even ask us to get out of the car. It had been a relief to find things exactly as they had been at Easter when we had come to organise our stay.

Very little had, in fact, been accomplished then, and it was only in June that word came from the Liszt Music Academy that we could go, giving us barely eight weeks to prepare.

The phone rang, and Rézi answered.

‘That was Péter. He'll meet you at the flat at five.’

I looked at the clock; just a quarter past four. No hurry then, as the flat which we were to rent from Péter was quite near, just across the Danube on the Buda side. I helped myself to more soda water and idly turned the pages of the Hungarian newspaper lying beside me. I wondered if I would ever learn this language.

At a party in England a year before we had met a Hungarian emigré who told us with some pride that it was a language impossible for a foreigner to learn. I wondered.

Rákóczi tér market : Courtesy Fortepan/Tamás Urbán

Miklós and Paul came back from the balcony and Rézi relayed the gist of Péter's call. Miklós picked up his small leather bag containing his identity card, travel season ticket and wallet, and we left together, this time using the lift, which we had not noticed in the dark of our arrival. Rézi waved from the balcony as we squeezed into the car, me sitting on the top of the luggage on the back seat, Miklós nursing my guitar in front.

It was Saturday afternoon, so all the shops had closed at one o'clock, but the cafés and cake-shop-cum-cafés (cukrászdák) were open and people emerged carrying parcels of cake. All along the Körút people were strolling, slowly pushing pushchairs and licking ice creams, looking into shop windows shaded by fading awnings. Others sat at tables under parasols, chatting and drinking as crowded trams rumbled past, watched by people on the balconies above.

We crossed the river from Pest to Buda and passed the many buildings of the University of Technology, then into a quiet street: Vántus Károly utca, a street of trees and small blocks of four-storey flats, with larger, ten-storey blocks not far away.

‘You are on the third floor. There's a lift, and you've got a phone,’ said Miklós. ‘Two minutes to five.’ Miklós looked at his watch with satisfaction. He prided himself on his punctuality and on his ability to estimate within a few minutes the journey time between any two places in the city. ‘And here's Péter,’ he added, seeing a bearded, portly figure approaching.

Péter, too, taught English, and was to spend the following year in London. His wife, Éva, had decided that she would spend the year with her parents in Dabas, some thirty miles outside Budapest. Hence their flat was free for us. We all shook hands, then Paul and I followed Péter and Miklós into the building and up to the third floor.

The flat was minuscule: one room, a kitchen, bathroom and narrow hall. Every possible space had been utilized - even the phone had to be housed in the meter cupboard by the front door. Péter explained the workings of the washing machine, the cooker, the gas water heater in the bathroom, and the sofa bed.

He told us that, if anyone asked, we were to say that we were relatives of the man whose brass plate was on the door. In point of fact, Józsi-bácsi had died some years before, but it was bureaucratically expedient for Péter and Éva to perpetuate his supposed existence. Moreover, Józsi-bácsi, had he but known it, was at that moment up to his ears in organising a flat swap.

Most flats in the city belonged to the council and were rented out for a nominal sum. The size of flats was always described in floor area and they varied from small ones of about thirty square metres, having one room and a kitchen but sharing a bathroom (often outside) with other tenants, to flats of up to two hundred square metres.

Originally, the council allocated flats according to size of family, but later single tenants or small families occupying the larger flats had been forced either to move or have their flats partitioned.

By now, however, in 1982, it was quite common to find one elderly person occupying a four room, one hundred-square-metre flat, while next door a family with two or three children were living in one room with grandparents in the only other room.

Since council flats could not be owned, they could not be sold, so there was much flat-swapping. Thus, a couple like Péter and Éva and their young son wanting to move to a larger flat would advertise in the newspaper.

Similarly, an elderly person in a flat so large that they could no longer cope with cleaning or heating it, would advertise for something smaller. And so a swap would be arranged. Pages of advertisements were to be found in the newspapers and it was such a swap that Péter and Éva were in the process of finalizing.

So far the practice was entirely legal; however, the person offering the larger property always asked for a huge sum of money, possibly several hundred thousand forints (equivalent to four or five years' earnings) and this was totally illegal.

Péter and Miklós chatted for a while in Hungarian, leaving Paul and me to look around. From the window I could see a low, brick building with a playground surrounded by trees, presumably a school, and beyond was a ten-storey block of flats typical of many areas of Budapest. Unhappily, I saw no record player or tape recorder; music was the core of our lives and it would be difficult to live without it until our things arrived from England.

‘Where's the nearest shop?’ I asked Péter.

‘Well, there are a couple of small ones in the next street: a butcher, a greengrocer and grocer, but if you walk a bit further there's an enormous shopping centre called the Skála. You can buy everything there from food to furniture. By the way, if you see any washing powder you should buy it. There's been a shortage, and though we've left you some, you'll soon need more.’

Whether it was the washing powder itself that was in short supply or the card used to make the boxes became the subject of a short debate, but whatever the reason, I made a mental note to buy some as soon as I found it.

After helping us to unload the car and carry things up to the flat, Miklós left, promising to phone the next day, while Péter arranged to see us later that week before he left for England.

Main photo: Rákóczi tér : Courtesy Fortepan/ Hlatky Katalin-Főkert

LATEST NEWS IN community & culture