An Englishwoman's Life in Communist Hungary: Chapter 2, Part 6.

- 28 Nov 2022 4:23 PM

Now You See It, Now You Don’t and House of Cards have been included as part of the Open Society Archive dedicated to this period in the CEU. You can read a serialisation of them here on Xpatloop. You can also buy the dual-volume book on Kindle as well as in Stanfords London.

Chapter 2: Snow and Settling: Dózsa György út

Part 6 – Hungary’s “flat problem” - and another move

1983, and the snow mounds began to melt at the sides of the road, the drains filled to overflowing and just walking down the street took on an aspect of Russian roulette: the road was a lake of dirty, melting slush from which you were drenched by passing cars and buses, whereas hugging the walls of the buildings left you vulnerable to avalanches of melting snow sliding off the rooftops.

Daily life resumed its pattern of teaching and seeing friends. The days became longer, and the eager anticipation of the coming spring was almost tangible. The combination of dark, cold days and the general lack of fresh fruit and vegetables in winter caused Hungarians to yearn for any sign of spring's arrival, to deliver them from what they called 'winter tiredness'.

Spring, when it does come, is a sudden eruption: temperatures rise by ten degrees, the sun shines all day, stalls fill with the vivid smells and colours of spring flowers and vegetables, and winter clothes are put out of sight in the firm knowledge that this is it.

Following the arrival of spring (always dated from March 15th, the national holiday marking the anniversary of the 1848 Hungarian uprising against the Austrians) there is a gradual but relentless increase in temperature right through to July.

August gives way to the annual 'Indian summer' of September when days are still like summer, but cooler mornings and evenings portend the arrival of autumn. The change from autumn to winter is often as dramatic as that from winter to spring, each season usually being quite clearly distinguished from the next.

It was on such a morning in February, on my way to teach at Lingua, that I found myself at the HÉV terminus with no train in sight. A small group of people was looking at a board bearing the information that the HÉV was not running, and a bus was going instead. I found it and boarded, there were not many passengers. In good time before my stop I stood up and pressed the halt button above the door – an indication to the driver you want to get off. He did not stop.

I looked around, but everyone else was either reading or looking out of the window. I watched with alarm as I saw the Lingua building disappear from view and realised I had no idea where I was going. The bus continued to a distant terminus where I disembarked with everyone else, realising that if I stayed on I would no doubt be taken past Lingua once again and back to my original starting point. I flagged down a passing taxi instead.

Back at home the whimsical gas water heater in the bathroom refused to light. Having learnt that in such situations it is best to ask a friend to recommend someone to mend it, I mentioned it in passing to our doctor neighbour a few days later.

He said he would arrange something, and we imagined he would let us know within a few days. Thus, we were dumbfounded to find two gasmen on our doorstep at eight o’clock the following morning. They marched straight into the bathroom, mended the heater in a matter of minutes and then made to leave.

I quickly rummaged for my purse in my bag, but they categorically refused the proffered note. It turned out that our surgeon neighbour had operated on their boss's leg, and he had strictly instructed his workmen not to accept any payment.

A few days later I came home to find Éva waiting for us. Communication was limited, since she spoke no English and my Hungarian was extremely basic. As far as I could understand she was telling me that we would have to leave the flat, it was something to do with the gas, but this I could not follow.

Soon Paul was home too, and with the aid of a dictionary we discovered what the problem was. Péter and Éva's flat belonged to the council, which was responsible for the upkeep of both the outside and inside of flats, apart from their decoration.

Éva wanted new gas pipes taken into the kitchen for hot water, along with some other modernisations which the council would complete at no cost. But it seemed that Éva had just been told that from the beginning of May tenants would be required to pay half the cost of such work, and they therefore wanted to have it done in April.

Since we could not live in the flat while the work was being done, and since Péter would be returning from England in June or July, we decided we should find a new flat to rent from April onwards.

Courtyard flats renovated Courtesy Wikimedia

As yet we had not had to flat-hunt in Budapest. Miklós had made all the arrangements with Péter for his flat whilst we were still in England. We knew there was an acute shortage of housing in the city and in seeming paradox, a large number of empty flats.

Council flats, which constituted the vast majority of housing, could be inherited. They could also be reclaimed by the council if a person died with no-one else registered as living there. Thus, every child in Budapest is registered as living with a grandparent or other relative, entitling him to inherit the flat when the grandparent dies.

In many cases, the grandparent dies while the child is still at school, so the flat remains empty until needed. So it was that thousands of empty council flats existed in a city where you could not even put your name on a waiting list until you had worked for five years, and where you would then in all probability have to wait a further ten or fifteen years before finally being offered a place to live.

Many young couples are thus forced to live in their parents' or parents-in-law's flat, and it is not uncommon to find three generations living together, in the best cases with each generation in a separate room, but commonly with grandparents in one room, and their children and grandchildren sharing the other room. Few flats were rented since the law favoured the rights of the tenant and foreigners were few.

It was also possible to buy freehold flats, but these cost many times the amount needed to secure a council one, and it was a totally impossible option for all but a few. A common, and rather morbid practice was that of a person making a contract with an elderly person who had no relative, to inherit their flat when they died.

The terms of the contract could vary between paying a lump sum in cash, making monthly payments, or even living in the flat of the elderly person and taking care of them until they died. It was thus obviously in the young person's interest to choose as old and as unhealthy a person as possible and hope they would not have to wait long.

One afternoon not long afterwards, Endre called in as he had promised at the time of our first meeting. He was carrying a variety of pipes. ‘I've been all over town to get these,’ he grinned. ‘You can't get them anywhere – they're delivered to the state shops but the assistants sell them at a profit to some small private shop, which automatically doubles the price knowing there are queues of people like me desperate to get them at any price.’

‘What are you mending?’ I asked.

‘The sewer,’ he replied, walking in and looking about him. ‘Not a bad place,’ he said. ‘Are you happy here?’

We sat down.

‘Well, we've got to move actually,’ and I told him the situation.

‘I might be able to help you,’ he replied. ‘I know, come over on Saturday and have lunch with us and we'll talk to Kati about it. We may have a place for you.’

He wrote down his address on a scrap of paper, refusing the tea I offered to make. ‘No, I must go and get on with the sewers, but we'll expect you on Saturday.’

Then flashing a characteristic grin, he picked up his armful of pipes and left.

Filling station by the City Park and Endre’s home Courtesy Fortepan/UVATERV

On Saturday morning we looked at the map and found we would be able to get to Endre's by walking through the city park, only a fifteen-minute walk from door to door. They lived in a small bungalow with a small, unkempt garden, together with their seven-year-old daughter Flóra and a cat.

Smells of fried chicken wafted out from the kitchen window and we were soon seated around the table in the sitting-room. The walls were lined from floor to ceiling with books in various languages, Polish, English, Russian and Hungarian, magazines were piled on stools and in corners.

Conversation soon turned from Kati's and Endre's various jobs of teaching or interpreting to their abortive attempt to defect from Hungary the previous year, and their reasons for wanting to leave. Unlike our other friends, Endre had not a good word to say for the ruling government.

‘Everyone's corrupt, the system's corrupt, but it's not that which is so awful, it's that it doesn't work. Everyone's cheating everyone else – you get someone to do a job for you, they overcharge you, you tip them for indifferent work and a week later it's gone wrong again.’

I could not help but think of our experience with the removers, where we had been forced to pay and tip someone and then had to move all our things ourselves.

He went on in the same vein about the disastrous state of the economy, the total inefficiency of companies, the obstructive bureaucracy, and the corruption and bribery to be found on every level of life from getting your child into university to buying the few pipes he had needed. And yet he always laughed as if describing something he had read about in another country, he seemed neither bitter nor depressed.

Their additional month in Germany had cost both of them their jobs, and their passports had been confiscated for four years.

‘Oh well,’ said Endre, ‘it's not the first time. I tried to walk over the border into Yugoslavia when I was sixteen, but I was caught. My right to a passport was taken away then too.’

Red passport issued for travel to other Eastern bloc countries only

‘Endre! We nearly forgot to tell them about the flat!’ Kati interrupted.

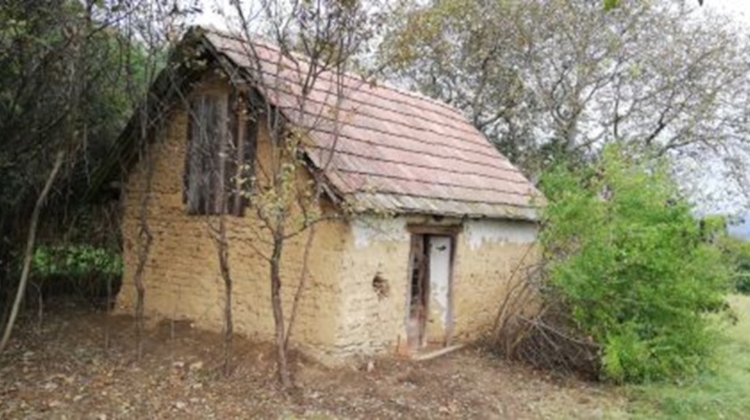

‘We may be able to get a flat for you in Garay tér – do you know where it is? It's just a few streets away from where you are now. I don't know what condition it's in, it's been empty for years. It belongs to a school friend of mine who's in Canada now,’ Endre continued. ‘I'll go round and see the old man, her father, this week.’

We chatted until late, agreeing that Endre would drop in with news of the Garay tér flat during the week. He accompanied us back through the park, still deep in conversation about philosophy and politics, gesticulating expansively.

He came, as agreed, a few days later, and suggested he take us to see the flat on the following Sunday. He seemed doubtful that we would want to live there but would not be drawn as to why. But time was short, and as yet no-one else had come up with any concrete possibilities, and somehow, though we had hardly discussed it, Paul and I already knew we would be staying another year. We leaned over the railing and waved to Endre as he crossed the courtyard below.

As though he also sensed our unspoken decision he smilingly shouted up, ‘You're both crazy, you know that!’

We laughed. He was neither the first nor the last to say so.

‘Sunday at ten, then! Cheerio!’ he called, and disappeared into the deep shadows of the gateway.

Main photo: HÉV stop Courtesy Flickr

Click here for earlier extracts

LATEST NEWS IN community & culture