An Englishwoman's Life in Communist Hungary: Chapter 3, Part 2.

- 13 Dec 2022 9:38 AM

Now You See It, Now You Don’t and House of Cards have been included as part of the Open Society Archive dedicated to this period in the CEU. You can read a serialisation of them here on Xpatloop. You can also buy the dual-volume book on Kindle as well as in Stanfords London.

Chapter three: Market and May Day: Garay tér

Part 2 – Our supervised move; a local eatery and its dubious clientele

Then began the arduous task of carrying the boxes up the sixty-odd steps to the second floor. In most cases we stopped and sat on the box on the first floor before continuing. All the boxes were dumped in the room next to the kitchen which we had decided we would use to store them when they were empty, and also for any furniture in the other rooms which we did not want.

About half an hour after we arrived, two elderly women walked in through the open door without ringing the bell. Endre appeared to know one of them. She looked critically at us all, and he then introduced us to Rózsi-néni (Zoli-bácsi 's wife) and her sister.

Together we walked into the main room which looked considerably transformed. The newspapers and paint tins were gone, though tools and beer bottles still graced the table and marble top of the dresser.

Rózsi-néni looked around her as though it had been a long time since she had been in the flat. ‘We used to have that room when we were first married,’ she said, nodding in the direction of the smaller of the two side rooms.

‘Which room are you going to sleep in?’ I told her we had decided on the other, larger room, the only problem being that there was no bed. In fact it had only just struck me how bare the sitting room also was, with no armchairs or sofa, just the dining table and four dilapidated chairs.

There then ensued a rapid conversation between Rózsi-néni and Endre after which he suggested going off in the van to a large second-hand furniture shop and getting a bed. The remaining boxes were off-loaded into the street.

The van driver was given instructions how to get to the shop and disappeared with Rózsi-néni and her sister. Endre, Paul and I headed for the bus stop telling the others to drink lots of beer and that we would take them all out for a meal when we got back.

Rózsi-néni and her sister were already strolling round the 'French' beds when we walked into the shop. It was a cavernous, dark place with brown lino floors and poor lighting, and the furniture was either vinyl or had gaudy floral covers.

After looking around and finding a perfectly acceptable bed, the assistant, who was smoking and drinking coffee with the cashier, was summoned. It turned out that the price of the bed included two similarly floral-patterned armchairs, so that solved the problem of furnishing the sitting-room. We paid and walked out to the hot, dusty pavement.

Endre told us he had to go, he had a job interpreting that afternoon, but organised the van to take us back to Garay tér with the bed, while the two old women would get a taxi. We were unable to communicate with the driver of the van and were surprised when he suddenly stopped in a side street near Garay tér. He wound down his window and shouted someone's name.

Above us a window opened and a young lad looked out. There followed some more shouted conversation after which the lad emerged from the building and jumped on the back of the van, travelling along sitting in one of the armchairs.

The driver smiled at us, and taking his hands off the wheel, cupped the biceps of one of his arms with his other hand and pointed to his friend in the back. Then pulling a mock-sour face he squeezed the top of Paul's left arm and grinned. We all laughed and I mimed playing the piano then pointing to Paul, at which he nodded and slapped Paul on the shoulder.

Second-hand furniture shop Courtesy Fortepan/ FŐFOTÓ

Back in Garay tér only the neighbour was in the flat. The others had left a written message that they would be back in an hour. The boxes were neatly stacked and some beer bottles stood on the kitchen table.

Within minutes we heard the voices of the two women coming up the stairs into the flat. Looking over the railings we saw the two men were just manoeuvring the bed past the dustbins and were obviously suffering under the weight.

We walked back into the flat to find the women trying to decide where the bed should best go. Unfortunately, our opinions differed. Paul, meanwhile, had taken a few hundred forint notes out of his wallet and put them in his pocket where they would be more accessible.

As the men reached the door of the flat their shirts were sticking to them. One of them took his off and hung it on the door handle. Once through the hall and main room the two old women began to give instructions as to where they thought the bed ought to go, whilst I tried in vain to persuade them to put it elsewhere.

Everyone was hot and tired, and the two men were understandably indifferent as to the position of the bed in the room, and impatient with all the contradictory instructions they were being given.

Paul, in an outburst of frustration, shouted, ‘If only someone could speak English!’ at which point the young lad the driver had picked up put his end of the bed down on the floor and said, ‘I can speak English, I was born in Northampton.’

The van driver looked even more amazed than we did. He obviously had no idea that his friend could speak English. I fetched some beer from the kitchen, the two old women left and the four of us sat on the bed - now exactly where we wanted it. It turned out that the parents of the young man had gone to England in 1956 but by the time their son was thirteen had decided to return to Hungary.

He then went to a Hungarian school and had never had any reason to speak English. In fact, he spoke well, though hesitantly, searching for words he had not used for years. They finished their drinks, brought up the chairs and, accepting the money as a matter of course, left, deep in conversation.

Area around our flat Courtesy Fortepan FŐFOTÓ

It was half past one. Our friends had reappeared, so we locked up the flat and walked out into the street. The market gates were open, but only a few stallholders remained, sweeping up cabbage leaves and the odd squashed tomato, and carrying their wooden crates back to their cars - a Volvo, a Mercedes and Ford among them.

Next door, on the other side of our building to the car workshop, was a small café. We looked at the menu in the window but decided against it. We wandered down the road past a shop full of a vast range of sieves and winepresses, a shop selling what was described as 'colonial' furniture and on to the corner. On the opposite side of the road was another possibility called 'The Family Circle'.

Outside on the pavement sat a man, a beer bottle to his mouth. Another man in faded blue trousers and vest, his paunch hanging well over his black belt, stood with a woman of indeterminate age, with dyed carrot hair, platform shoes and smoking. The others seemed dubious, but Miklós led the way through the door. Noise and smoke filled the air.

The first area we walked into had a long bar with a sink at one end, stacks of glasses piled high, and many smaller bar tops of chest height dotted about, at which people were standing and drinking. The floor was stone and covered with matches, cigarette ends and beer.

People were laughing raucously, shouting and gesticulating. To one side was a thick curtain which we pushed through to get to the dining area. This too had a stone floor, small tables and red, vinyl covered chairs. It was marginally less smoky and noisy and in the corner were two empty tables which we quickly pushed together. The waiter arrived, clad as in every restaurant in dark trousers, a white shirt and bow tie.

The food was excellent, fried beef with a mountain of onions and potatoes. We seemed to attract a certain amount of attention, possibly due to the language, probably also because the others were regulars. A sound of shouting and broken glass came from the other side of the curtain. No-one around us took any notice.

We paid and left, pushing our way as quickly and unobtrusively as possible past what looked like becoming a nasty argument. A moment after the last of us got out through the door, the bartender hustled a customer, cursing and shouting, out on to the pavement.

He began to explain his situation to the man we had passed on our way in, who was still sitting there, and then turned around and swaggered back in.

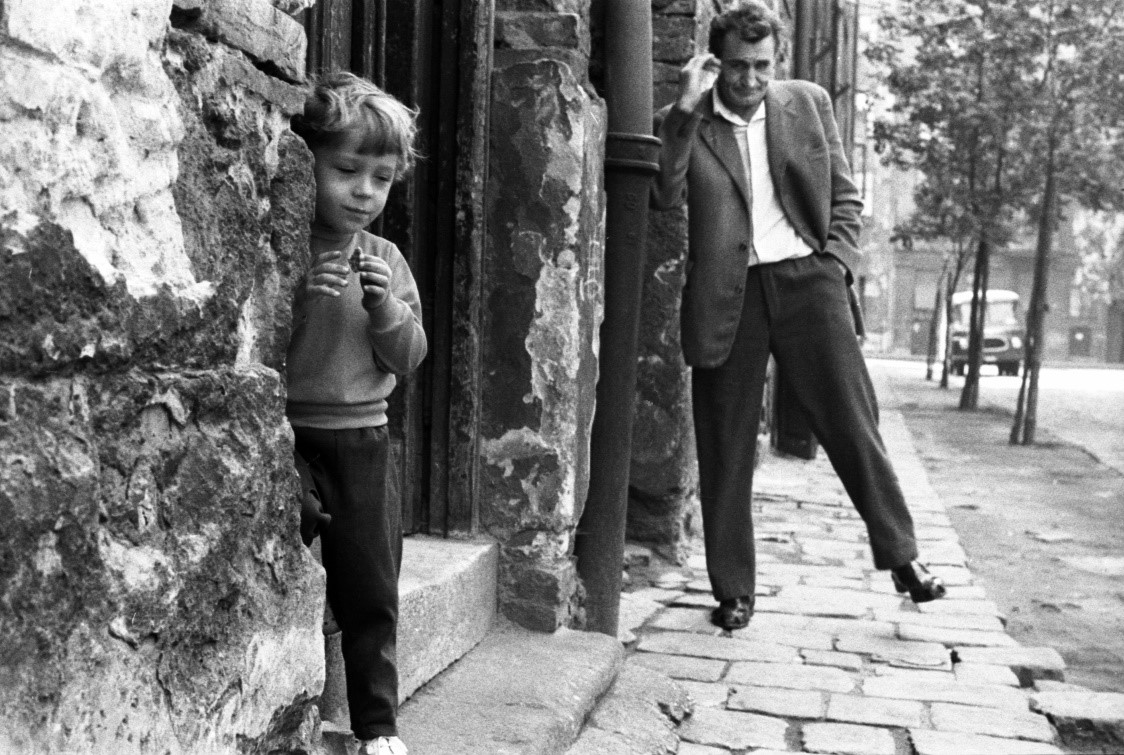

Going home from the pub Courtesy Fortepan/ Zoltán Szalay

We crossed back over the road and thanked our friends for their help. There was a sudden shrieking and yelling and this time the customer who had already been ejected once, was pushed out again not only by the bartender but by the waiter too. By one hand he was pulling a fat middle-aged woman in a stained dress by her long, greying hair.

They stumbled across the road, he still shouting at the bartender and waiter who had remained standing on the pavement, she shrieking at him. For a moment it seemed as if the man was going back again, when a police car rounded the corner and stopped outside. The man and woman then shambled off, while the man still sitting drinking on the pavement began to fumble in his pockets for his identity card.

Click here for earlier extracts

Main photo: Garay tér pub Courtesy Fortepan/ Magyar Rendőr

LATEST NEWS IN food & drink