'An Englishwoman's Life in Communist Hungary': Chapter 3, Part 11.

- 13 Feb 2023 12:58 PM

Now You See It, Now You Don’t and House of Cards have been included as part of the Open Society Archive dedicated to this period in the CEU. You can read a serialisation of them here on Xpatloop. You can also buy the dual-volume book on Kindle as well as in Stanfords London.

Chapter three: Market and May Day: Garay tér

Part 11 – Salgótarján glass factory teaching; 1978 flashback

I had brought my cello back with me from England that summer with the intention of restarting lessons (I had had four months' tuition in England), in all probability with one of Paul's students.

Thus it was, that on the last Sunday in September, I met Zoli. He was twenty-one, had quite a good passive knowledge of English and was an extremely talented cellist. He came literally skipping up the stairs at Garay tér to start teaching me.

It was only that morning that I had taken the instrument out of its case, and found that the fingerboard, which had been slightly loose in England, had actually parted company from the rest of the cello.

Luckily, Zoli had brought his own instrument with him. He looked surprised when I suggested I play on it, but then agreed, and asked me to play a scale. After playing just a few notes, Zoli stopped me.

‘What do you think of how it sounds?’ he asked me.

I began to try and excuse myself, saying I had not played for a year and that anyway I was a beginner and my teacher in England, a member of a leading British Symphony Orchestra, had said I could hardly expect to make a good tone so early on. Zoli did not comment.

Then, ‘What about your thumbs - don't they hurt you?’ he asked.

I was amazed: my thumbs were not hurting then, after only a minute of playing, but they definitely had hurt in England after about twenty mintes' practice.

When I had asked my teacher about it she had simply told me that I was using my muscles in a different way from when I played the piano, that I should not practise too much and I would get used to it.

‘How do you know?’ I asked Zoli,

‘I can see from the way you hold the cello and especially how you hold the bow,’ he replied.

We decided that I should begin again from the beginning, and the remainder of the lesson took place in the bathroom - much to the amusement of Paul who, returning from shopping, found us both bent over the half-filled bath dragging a face-cloth up and down on the surface of the water.

My homework was to consist of this daily exercise, plus others such as picking up salt cellars off the table, or holding the top of the back of a chair and swinging it towards me on its two back legs, always checking that my thumb muscle was soft and relaxed - 'loosey' as Zoli said.

At the end of the two-hour lesson, I asked Zoli what I owed him. He looked offended.

He said that when Paul asked him if he would teach me, he had decided it would be good for him, and so he wanted no payment. As we walked towards the door, I tried to stuff a one-hundred-forint note into his pocket; for a moment he looked hurt then, hoisting his cello onto his shoulder, he dropped the money on a chair and ran down the steps two at a time, waving and smiling as he went.

Thereafter it was a weekly battle to get him to take any payment.

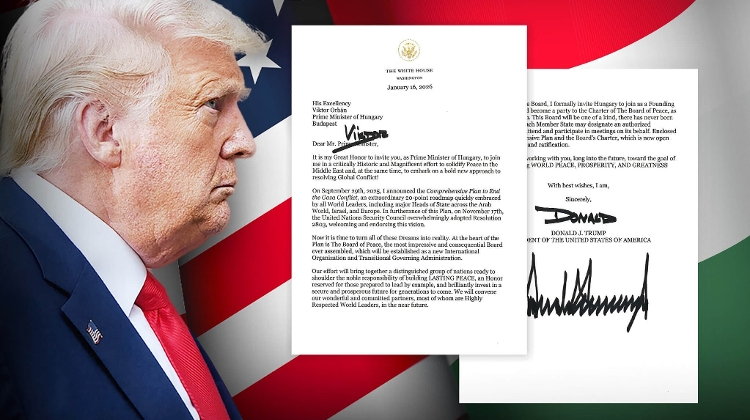

At the end of October, I had agreed to teach at one of Lingua's country courses, this time at a glass factory in Salgótarján, a town in the north, close to the Czechoslovak border.

It meant going on a Sunday and returning the following Saturday afternoon. I decided to drive, since the flat I was to stay in was at the opposite end of the town from where I was to teach, and I would otherwise have to catch two buses each way.

One of the two glass factories Courtesy Fortepan/ Magyar Rendőr

I made a last trip over to Lingua to collect the books, cassettes and other teaching materials I would need and then, taking heed of Miklós's advice and my experience of the weather in the Bükk at Feri's, I packed some warm clothes and finally my cello bow - I was now at last permitted to pick it up though not to use it on the cello.

I left on the Sunday afternoon and it was already dusk as I passed the town of Hatvan, its name 'Sixty' indicating its distance from Budapest. Many towns and villages have quaint or funny names when translated, for example the villages of Sári (Sarah) and Bugyi (knickers). It is well known joke that to get to Sarah you have to go through knickers!

The two-lane motorway was dimly lit, had no cats' eyes, inadequate road signs, and the frequent road works were so badly illuminated and signposted that I did not wonder at the many road accidents that occurred.

At the permitted maximum speed of sixty kilometres-per-hour and with the poor lighting, it was all but impossible to react to the obstacle course of lane changes.

However, driving through the smaller villages which have no street lighting at all was far worse. Here there were a preponderance of peasant cyclists in black clothes and with no lights on their cycles, swerving from one side of the road to the other, in states varying from the mildly tipsy to the totally paralytic.

Salgótarján was in a long valley, a town of one steel and two glass factories with its inhabitants housed for the most part in prefabricated concrete blocks of flats. Its one redeeming feature is the wooded hills that lie between it and the Czechoslovak border, but in late October the trees were already bare and so my impression remained unfavourable.

The students were friendly but rather distant in comparison with those I had taught in Baja and Orosháza, not only with me, but with each other.

The canteen food, a highlight at the sister glass factory in Orosháza, was here practically inedible, especially the honey-sweet tomato soup.

I was shown round the factory which was of course interesting, and it made me curious to know if factory workers in England also had to work in such searing temperatures, dust and noise.

I was given a small box containing five breathalyser tubes from one of the students who regularly had to use them to monitor workers dealing with machines, and subsequently to send them home if the result showed positive.

Glass factory canteen, Salgótarján Courtesy Fortepan/ Sándor Bauer

It was a quiet week in this quiet town, and I created a stir as I drove through the centre at seven-thirty - certainly few tourists go to Salgótarján, particularly in a right-hand drive car where the driver seems to be absent to anyone giving no more than a cursory glance.

A policeman, substituting for broken traffic lights at one junction, stopped waving his arms about to stare open-mouthed as I went past. The great gossip of the time was a story concerning a group of housewives who had set up a brothel in the home of one of their number which had just been uncovered by the police.

Otherwise, life consisted of shift-work at the factory and family life in concrete blocks, and an occasional trip to the one cinema or the concrete shopping centre. It would be untrue to say that I was not glad to leave and head back to Budapest on a sunny, frosty Saturday lunchtime, leaving Salgótarján a receding image in my rear-view mirror.

Keleti station - Courtesy Fortepan/ FŐMTERV

Back in Budapest I felt that winter had almost arrived. Standing waiting for my No. 67 tram at Keleti station I watched as the many stone blocks in the pedestrian area below road level were cleared away - blocks on which students and travellers had sat in the sun, peasants from the country waiting for trains home on summer afternoons or tired men drinking beers in the early evening after work.

Coach loads of tourists had dwindled to all but a few Polish ones in the car park behind the station, and the black leather coat brigade was once again becoming evident.

As November progressed our thoughts turned once again to Christmas and the train journey to Germany. This time visas and tickets were procured without difficulty.

Buying presents was time-consuming but enjoyable, especially from the small street stalls, and it was while wandering along the Körút towards Margaret bridge that I suddenly found myself in Fürst Sándor utca. A slight feeling of panic seized me as memories flooded back from five years before.

It was in 1978 that our whole relationship with Hungary had begun. In writing both his Ph.D. and a book on the composer Liszt, Paul had applied for, and received, a two-month British Council scholarship to work in Budapest.

We travelled together to Victoria station on January 31st and Paul began the twenty-four-hour journey to Budapest. He was met at Keleti station by Miklós who took Paul first to the police station to register him, and then on to the accommodation that had been arranged for him in a flat in Fürst Sándor utca.

The flat belonged to a fifty-year-old divorcee, Mrs H., whose son was at university.

The flat was quite large and comfortably furnished with antiques and oil paintings.

Home of a wealthier person Courtesy Fortepan/ Szilvia Lugosi

Mrs H. spoke no English, so when Miklós was not there to interpret, communication between herself and Paul was limited to their mutual knowledge of basic German.

On arriving, she asked Paul, through Miklós, if he wanted her to provide him with breakfast and an evening meal. He agreed and asked how much it would cost, his accommodation already having been paid for by the Hungarian equivalent of the British Council.

She dismissed the question out of hand and Miklós suggested to Paul that he buy her some presents at the end of his stay since she was refusing money. Then, after writing down enough Hungarian words to enable Paul to buy an airmail letter from the tobacconist next door, and arranging to come at eight o’clock the following morning, Miklós left.

Although employed to interpret for only three days, Miklós and Paul became firm friends and met almost daily.

Miklós began to teach Paul the rudiments of Hungarian while Paul gave Miklós the then rare opportunity of conversing with a native English speaker.

Occasionally Miklós would give Paul a Hungarian lesson at the flat, but Paul soon realised that, for some reason, this appeared to trouble Mrs H.

‘Has Miklós been here again?’ she would ask upon her return from work, looking at the cigarette stubs in the ashtray. It was obvious that she did not like him, nor did she approve of Paul's continuing friendship with him.

I was to visit Budapest for the last two weeks of Paul's stay and we would return to England together.

Paul approached Mrs H. with the idea and asked if I could bring some things for her from England since she would not accept payment for our food. So, I received a list: jeans and a denim jacket for her son, a skirt and blouse for her, whisky, cassettes and various other items.

When I discovered that the train fare to Budapest was exactly double the air fare, I bought two return air tickets so that Paul could fly home with me.

The flight was bumpy, but the tasty meal and unlimited quantities of wine amply compensated. A bus took us from the plane to the airport building where long queues formed as a result of the minute examination given to every passport and visa.

I staggered through the customs with my two heavy cases. I was stopped.

‘Please open your cases.’ I did. The customs officer held up the new jeans. ‘Are these presents for somebody? And what about the whisky and these cassettes?’ Something warned me not to tell the truth.

‘They're for my husband, he's been here for two months, he's studying here,’ I replied. Luckily there were no more questions.

Budapest Airport Courtesy Fortepan/ Sándor Bauer

Click here for earlier extracts

Main photo: Salgótarján - Courtesy Fortepan/ András Mezey

LATEST NEWS IN community & culture