'An Englishwoman's Life in Communist Hungary': Chapter 3, Part 14.

- 8 Mar 2023 12:20 PM

Now You See It, Now You Don’t and House of Cards have been included as part of the Open Society Archive dedicated to this period in the CEU. You can read a serialisation of them here on Xpatloop. You can also buy the dual-volume book on Kindle as well as in Stanfords London.

Chapter three: Market and May Day: Garay tér

Part 14 – A home visit from the police

September passed with no new developments, but at the beginning of October Rózsi-néni called again. ‘How is Zoli-bácsi ?’ we enquired.

‘No better,’ she sighed. ‘I really came to tell you that I have advertised the flat and one or two people want to come and see it.’ She paused. ‘What are you going to do? Are you going back to England?’

‘Oh no,’ we replied. ‘We'll find another place to rent,’ we said, more optimistically than we felt.

Rózsi-néni did bring some people to look at the flat but we heard nothing of whether they wanted to buy it. However, we had already begun to tell all our friends, acquaintances and students that we were looking for a new place to rent.

One day, still in October, I had just come home from teaching early in the afternoon when there was a knock at the door. Standing outside were two men in suits, one of whom looked vaguely familiar. They produced police IDs and asked if they could come in. Only one spoke, the other just looked on. Casually they walked along the hall towards the sitting room.

‘I'm from KEOKH,’ said the man whose face I thought I knew.

‘Yes, I remember,’ I replied.

‘How long have you been here now?’ he asked, again in a casual manner. I wondered what on earth this was all about, what we could possibly have done to warrant a visit and where the conversation might be leading.

‘Do you mean in Hungary?’ He nodded. He knew the answer of course: every detail of our stay was documented in KEOKH. ‘Two years,’ I replied.

‘And how long have you been here in Garay tér?’

‘Just over a year,’ I said.

‘May I look into the other rooms?’ he asked. ‘We always like to see that foreigners are suitably accommodated,’ he added by way of explanation. I led the way, both men following into the two small bedrooms leading off the sitting-room. ‘Are you satisfied with the flat?’ he asked.

‘Yes, of course.’

‘Who is renting it to you?’ I told him.

Everything seemed to be falling into place. He paused. ‘Well, thank you, I think we'll be going now,’ he said as they headed back along the hall. ‘Goodbye,’ said one, while the other merely nodded his farewell. ‘Goodbye,’ I said, closing the door, feeling unsettled. I could hardly imagine that our living conditions were of any interest whatsoever to the police, and if they were, then why had they come only now after two years? No. Endre must have guessed correctly, and somehow the police had already become aware of Rózsi-néni's scheme.

Early in November János told us of a flat we would probably be able to rent, on the second floor of a house in Színyei Merse utca. It belonged to József, a colleague of János's wife who worked at UNESCO, and János arranged a time for us to meet József at the flat a week later.

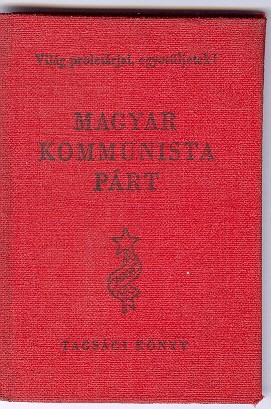

At about the same time, we had a visit from a woman we had never seen before. She called one morning and introduced herself as the local leader of the Communist Party. She said she had come to collect Zoli-bácsi 's party membership book as he had recently died. We had heard nothing of this, and told her that we had no idea where the book might be.

We gave her Rózsi-néni's telephone number and she left. That same afternoon, Rózsi-néni arrived with her sister to collect the rent. Not quite knowing what to say with regard to Zoli-bácsi , we decided to feign ignorance.

‘How is Zoli-bácsi ?’ we asked.

‘No better,’ came the astounding reply.

We did not pursue the subject, but later asked our neighbour Manci-néni. ‘Oh yes, he died about a week ago,’ she told us. ‘I saw it in the paper.’

A few days later we went to see the flat in Színyei utca. The building was quite the worst in the narrow run-down street. Its greying pink plaster was falling off in chunks, and its stonework was scarred with countless bullet marks from both the war and 1956.

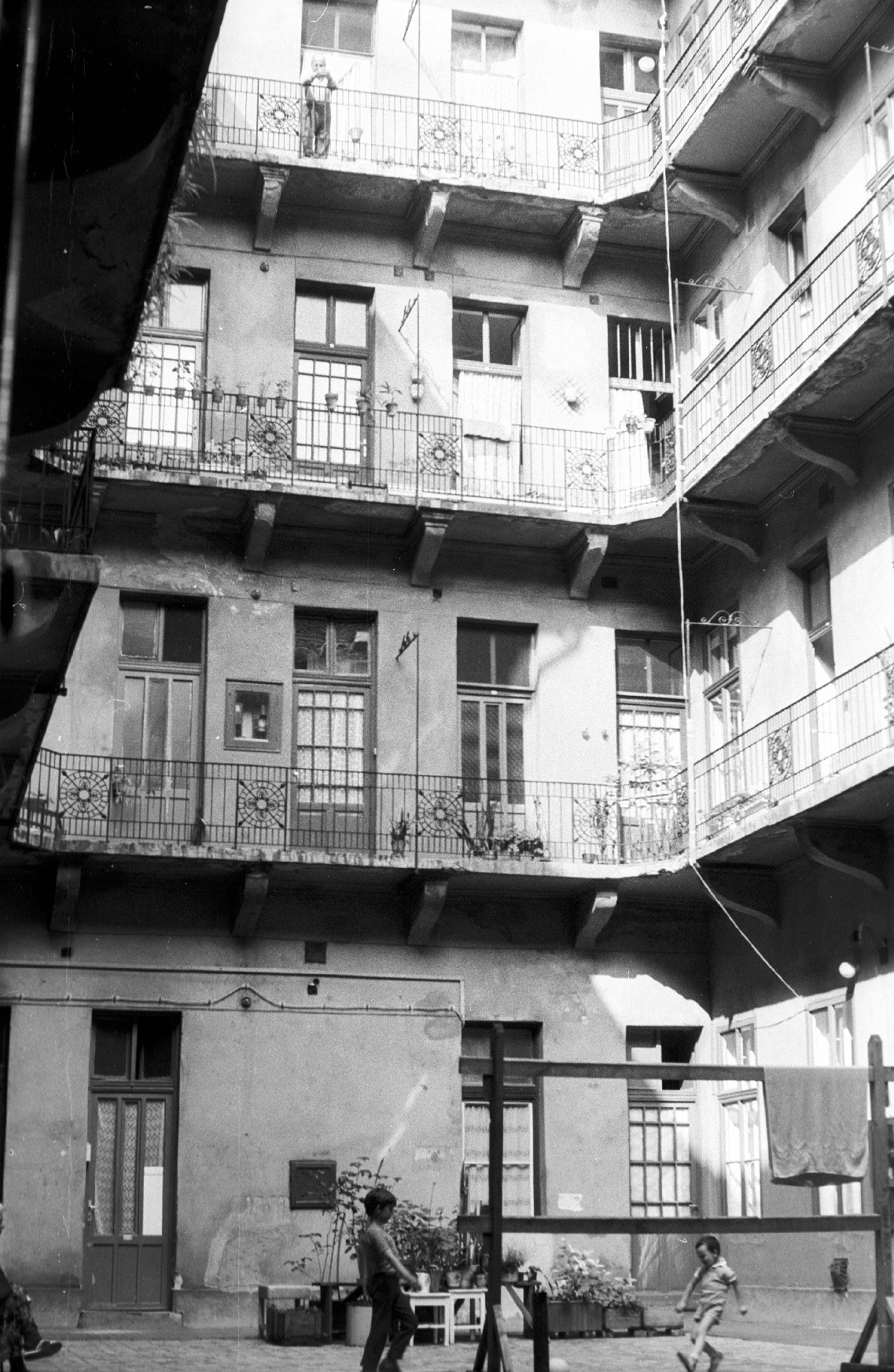

Unlike either the Dózsa György building or Garay tér, this had no pretensions to grandeur. The courtyard was an unrelieved area of concrete, empty but for a large iron stand on which carpets could be beaten. A strange, black wheelchair-type of contraption was parked outside one of the ground floor doors near the customary black bins and letter boxes.

Courtyard with stand for beating carpets Courtesy Fortepan / Lechner Nonprofit Kft. Dokumentációs Központ

We walked up the narrow winding staircase from the courtyard to the second floor. The walkway was equally narrow, and we found that József's flat was in the very far corner.

We knocked on the small brown door and József ushered us into a tiny dark hall, and then into a slightly less dark area containing a desk and a small cupboard. Leading off this was the room - this was a one-room flat as our first Budapest home had been.

The room was light and cheerful and had a beautiful wooden gallery. Wooden steps led up to a large platform on which one could sleep and store things, while underneath was a sofa, bookshelves and another desk. The room contained little other furniture. Leading directly off it came in turn the small kitchen and recently modernised bathroom.

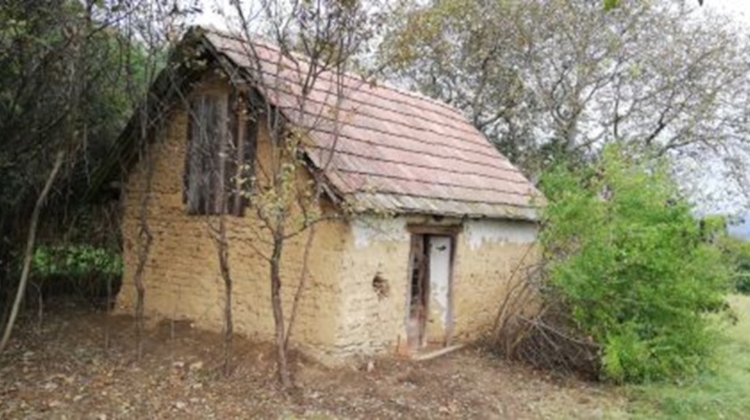

József explained that it was his wife's flat but that they had moved out of Budapest to a village just outside the city boundary; he hated the noise and pollution of city life. He wanted four thousand five-hundred forints a month for the rent, which considering the size and condition of the place in comparison with Garay tér's five thousand forints, seemed rather high.

But winter was approaching, and although no flat swap seemed imminent, we wanted to complete the move before the first snow. Endre had tried to persuade us to stay at Garay tér, but it seemed that even if Rózsi-néni could not carry out her plan, and even if Anna did not return from Canada, the council would take away the flat and we would have to leave anyway.

We agreed with József that I should collect the key from him in the last days of November, and that we would move in on December 1st. On our way home we decided to tell Rózsi-néni that we were moving on December 8th to avoid the sort of supervision with moving out that we had endured with our moving in.

Friends were asked to help, and two students I had been teaching privately for a year volunteered both their own help and that of a friend who owned a jeep.

Meanwhile, we brought up our old English boxes from the cellar and began the arduous task of packing.

Towards the end of the month I rang József at work and we arranged to meet at Színyei utca. When I arrived, he was already there. ‘Come in,’ he said, taking me into the main room. ‘Sit down. I'm afraid there's a bit of a problem.’ I waited. ‘It seems that my wife and I are going to be divorced, and she wants to come and live here.’ I was aghast.

‘But why didn't you tell us anything before?’ I asked. ‘We've nearly finished packing and we've told our landlady we're moving out in a couple of weeks, and we haven't got anywhere else to go!’

‘Don't worry,’ said József, ‘she couldn't possibly live alone with the children; she's never lived alone. This all happened once before, and she didn't last the month here. And this flat is totally unsuitable for children, much too small.’

‘Well, what's going to happen then?’ I asked.

‘I've already given her an ultimatum. Either she moves out by the end of the week, or she stops threatening to. If you ring me on Friday at work, I'll let you know, but I'm quite certain she won't leave,’ he said.

Feeling depressed and helpless I started out for home. I could not believe that the situation could have developed so dramatically since our last meeting. I told the news to Paul, who was equally shocked.

We sat and looked at the sea of half-packed boxes all around us and wondered whether to continue packing, or start unpacking. We did neither until Friday when I rang József and he said we could go ahead, his wife was not moving out. He sent us the flat key and we finally completed the packing in an outburst of renewed enthusiasm and relief.

By the evening of November 30th, the red, flagstone floor of the hall was lined with boxes, and the black heavy furniture had been moved back into position in the sitting-room.

The Garay tér flat resumed its original atmosphere of silent anticipation of a return of several generations of now deceased occupiers. We removed our names from the post-box and the front door, and then, from the once again uncurtained window, we watched for the last time as the cat woman shuffled away from the gates of the silent market.

Click here for earlier extracts

Main photo: Szinyei Merse Pál utca - Courtesy Fortepan/ Szilvási Hagyaték

LATEST NEWS IN community & culture