Surprising Expats: Caroline Bodóczky, 55 Years in Hungary

- 15 Sep 2022 12:22 PM

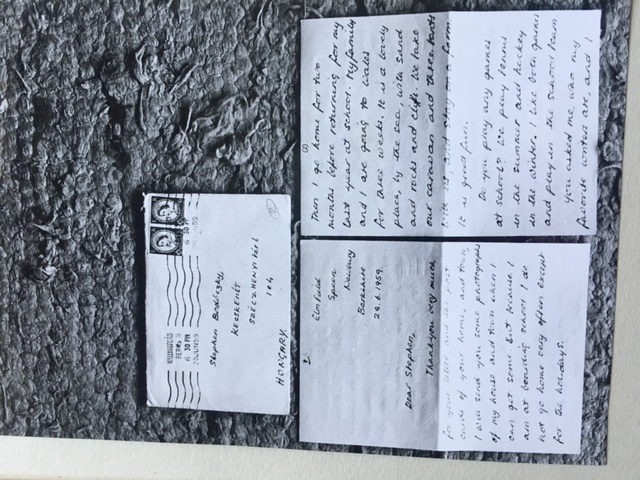

It was in 1958 that Caroline Griffin was asked by a friend at her English boarding school whether she would like to become the penfriend of a fifteen-year-old Hungarian boy living in Kecskemét.

“István’s English was not so good, but enough for basic communication,” says Caroline, who still has some of their early letters. “He used to send me cards with scenes of Budapest and other places – they had a 45rpm disc embossed into the card which you could actually play, with the music of Bartók and Kodály.”

Their correspondence continued even as Caroline moved to Canada to work for some years. Upon her return, she and a friend made the decision to hitch-hike around Europe; it was January 1966.

“Somewhere on our way towards Vienna, I thought: well, why don’t we see if we can get into Hungary?” she recalls. “By this time, I knew quite a lot of things about István – and he about me.”

“Visas were very expensive – and you had to convert $18 a day in Hungary – we were doing Europe on a frugal $2 a day! But there was a cheap 48-hour visa, so we got that.”

The journey eastwards was difficult with hardly any traffic in that direction. “The border was horrendous,” Caroline remembers with a shudder, “all barbed-wire fences and machine guns. It was pretty grim.”

To their good fortune, an unlikely lift was offered by a German travelling to Budapest in a Mercedes. It was January, the depths of an eastern-European winter and fog had descended, shrouding the entire landscape.

“It was rather beautiful, everything was white: there was thick snow; we went through the villages and all the women were wearing black clothes, long dresses and shawls – it was very eastern European. There were white geese being herded about….it was all black and white with the trees black against the fog and snow.”

“Luckily, the driver left us on the Pest side of Margaret Bridge – not that we knew what it was – and István was living in Pannónia Street just nearby. But it never occurred to me that it wouldn’t be his own flat.” István was, typically, living in a shared flat in which the landlady and her family also resided. Caroline and her friend found a student hostel for their one night in the city.

“You couldn’t even see the river – they burnt brown coal in those days and the smog was terrible; everything was filthy and people were morose. All the buildings were full of bullet holes, so it was a bit grim. It was very different from western Europe….no-one seemed to wear any colours.”

“The next day we decided to go to Kecskemét to meet István’s parents. We took the HÉV [suburban train] out to Soroksár and then at the barrier over the railway we walked along the row of vehicles to see if we could get a lift to Kecskemét.”

Eventually, they were offered a lift in a lorry on condition they were willing to ride with a group of country people in the back. “We got into the back under the canvas, it was dark so we couldn’t see anything at all, but we knew there were other people there. They were passing round a pálinka [fruit brandy] bottle which we all had a swig of…”

With István interpreting, Caroline was quizzed about farming life in Canada, including the price of a pig. It then transpired that the lorry’s driver, Józsi, had failed to sell his pig at market in Budapest and that it was there amongst them in the back.

“It was at some point then that something came towards us out of the gloom, the size of a Shetland pony! It was huge! It was a mangalica boar and it had long ginger hair, curly hair all over it – I couldn’t get over it, I’d never seen anything like it.”

The following day, Caroline and her friend waited in vain for a lift on the main road to Belgrade but other than the odd horse and cart, there were no cars travelling in that direction. They returned to Budapest taking the night train out of the country – their visas had expired but with no language in common, the border guards let them pass.

“In the meantime, István and I had fallen in love,” laughs Caroline. “So, he actually asked me to marry him on that last evening, and I said yes. It was really very romantic.” Caroline returned to Hungary three more times that year (by train) and then in 1967 she obtained a visa to stay three months.

István was in his final year at the Academy of Fine Arts, as Caroline started to grapple with daily life in Budapest. “The ABCs [small food shops] were not very clean and there was this terrible thing about nincs [there isn’t any]. You asked for something very ordinary and back came the automatic and unapologetic response: nincs! The other thing that really struck me was that people didn’t smile.”

“After my three-month visa expired, I got another three months, but then they said I either had to get married and stay – or leave. We got married here, but not before MI6 had visited my father in England asking questions about us.”

“We were still in the rented room when I got pregnant and the landlady chucked us out,” Caroline continues. “If I’d had the baby there, I’d have had a legal right to stay.” They subsequently moved to the castle district, where their first son, Nicky, was born, and from there to Zugló. But on inheriting some money they decided to try and buy a small house, opting for Budakeszi.

“People thought we were mad because if you moved out of Budapest you couldn’t move back unless you had a job there. Even then, you’d have to wait ten to fifteen years for a council flat.”

There were at that time a very few other British people living in Budapest: Charlie Coutts, who had arrived in 1956 and worked at the radio, and two Englishwomen – Judy and Liz – who had also married Hungarians and arrived just prior to Caroline. The concept in those years of an ‘expat’ was unknown, and none existed.

“Liz and I both had western cars,” says Caroline. “I had a Beetle and Liz had a small Austin. And we had private number plates, so we used to get stopped by the police all the time, especially as we were the only women drivers.” The first two letters of car number plates at that time denoted the ownership of the vehicle: A was Állami (state-owned), B was Belügy (Home Office), while R was Rendörség (police) and H was Hadsereg (army). Privately-owned cars began with a C.

While István won art scholarships to support them, Caroline began teaching and then working at Hungarian radio writing and acting in Galaxy X, a series for teenage learners of English. Meanwhile, her sons Peter and Tony were born, but the radio work continued for fifteen years. “

Galaxy X shot me to fame,” says Caroline, “I once went into the National Bank and the woman said: are you really Caroline Bodóczky?”

In fact, Caroline’s name soon became synonymous with English and English teaching in Hungary since original materials could not be purchased from abroad, thus giving rise to locally published books and cassette recordings. Her voice became instantly recognisable since she participated in practically every such recording.

Offers of English-teaching posts also emerged, including at Budapest University’s faculty of Natural Sciences, and then in one of the burgeoning number of language schools. Their growth was made possible by an increasing interest in learning English, and the changes to employment law – it had previously only been possible to employ one person, this was now increased to ten.

Following the change of regime in 1989 and the suspension of compulsory Russian lessons in schools, there developed a desperate need for good English teaching. It was at this point that Caroline was recruited to the newly-founded Centre for English Teacher Training where she worked for seven years, and it was here that she completed an MA in Teacher Education and focused primarily on teacher training and mentoring. Her final teaching years were spent at the International Business School.

It is now fifty-five years since Caroline settled in Hungary.

Looking back she says, “I think the only time I was homesick was at Christmas, but we quickly established English Christmases. And we used to celebrate Guy Fawkes on November 5th, but as Hungary was still celebrating November 7th [anniversary of the Russian revolution] we were careful to burn the guy where no-one could see us in case they thought we were burning an effigy of Lenin!”

Caroline recalls a visit of Brezhnev to Budapest. “I was shopping with Tony at Astoria and there was going to be a parade down Rákóczi Avenue. They were bringing children along with red flags to wave so I decided to stay and watch.”

Standing under one of the trees that then lined that road, Caroline was joined by an old peasant woman who put her baskets on the ground, also stopping to see the parade. “Suddenly a huge flock of sparrows flew into the tree above us, and the old lady turned to me and muttered drily: even the sparrows have been told to come.”

Looking back at her life in those first years, Caroline says, “I think it was that the challenges of those early days were new and interesting, and any difficulties we had were compensated for by the fact that we were newly married and having children – perhaps the highlight of anyone’s life.

If you saw a queue, you’d join it and only then ask what you were queuing for (it was probably oranges or bananas). When you saw things you wanted, you bought lots of them. We didn’t have a fridge for a long time, we didn’t have a television or a washing machine and I had to wash the children’s nappies by hand.

I think the worst thing was the telephone – when we moved to Budakeszi there weren’t even any telephone lines. We had to wait eighteen years for a phone, we didn’t get one until 1994! But we had a lot of fun – we didn’t have much money, no-one did – but food and wine were cheap, and we had plenty of time for friends and family. All in all, they were good years.”

Marion Merrick is author of Now You See It, Now You Don’t and House of Cards and the website Budapest Retro.