Xpat Opinion: A Hungarian Butcher’s Fabulous Art Collection

- 9 Dec 2013 7:00 AM

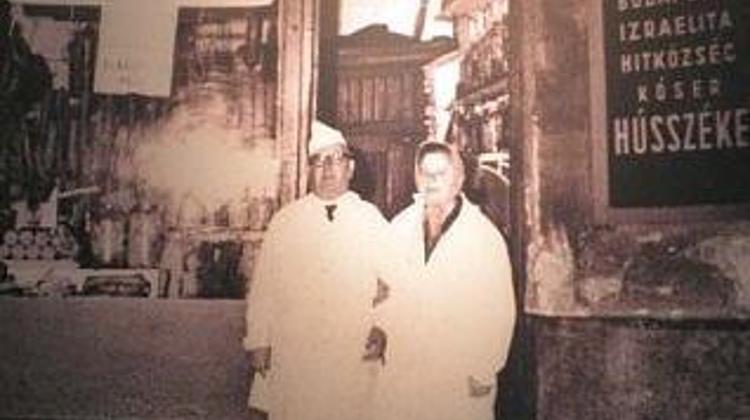

What inspired me to write about all this was an article in yesterday’s Népszabadság. It was about the public exhibit of a private collection of 230 Hungarian masterpieces. At the same time a book, The Secret Collection, appeared about the art works, written by art historian Péter Molnos. The collector of this treasure trove died in 1982 and he was, yes, a kosher butcher with a sixth-grade education.

István Kövesi, the butcher-collector, was one of the few “maszek” (abbreviation of magánszektor/private sector) store owners in those days. His kosher establishment was certified by the Hungarian Jewish religious authorities, but he couldn’t have made a go of the business if he had had to rely only on butchering. So he began making pickles of all kinds, for which the store became famous.

What could a well-heeled “maszek” (and most of the “maszek” store owners did in fact prosper) do with his accumulated wealth? Not much. He couldn’t have purchased real estate because a family could have only one dwelling in addition to the one in which the family lived. Buying gold was considered to be a crime. Nobody kept money in the bank because they didn’t want the state know about their wealth. So, some people decided, the smarter ones at least, that converting their cash into art might be a good way of dealing with the dilemma.

It seems that some other “maszek” success stories had the same idea as Kövesi did, but after the change of regime, once the original collector died, the heirs immediately cashed in and the paintings were sold to art galleries or new collectors. Practically no large collection remained intact. Kövesi’s two children, on the other hand, not only hung on to the 230 paintings by the greatest names in Hungarian art but also kept the collection a secret. With some difficulty the owner of the Kieselbach Gallery managed to convince the Kövesi children to allow the collection to be exhibited.

Why did they keep the existence of the collection a secret even after democracy arrived in Hungary? Most likely out of habit. After all, the collection had to be kept a secret because as far as the state was concerned, it was illegally gained wealth. Second, keeping 230 priceless paintings safe in an ordinary, not too well secured apartment in “újlipótváros” (Neue Leopoldstadt), formerly the Jewish section of Pest, was best accomplished if nobody knew about them.

However well pickles sold in Kövesi’s store, he couldn’t have bought nine László Mednyánszky paintings if the price of art had not been so depressed in those days. The poverty of precisely the kinds of people who would have been most likely to collect art was great. If anything, older collectors were selling off pieces of their collections, mostly to BÁV, Bizományi Áruház Vállalat, a consignment store that occasionally held auctions. Any kind of private art deal was illegal, although Kövesi eventually knew enough people in the art world that he managed to get some valuable pieces straight from the artists. It was also illegal to export any work of art from Hungary.

A former economics professor of mine, John Michael Montias, who was on the side an art collector, spent a year in Hungary in 1964-1965. He told me about people arriving at the regular auctions organized by BÁV with suitcases full of cash. Perhaps István Kövesi was one of them because there was at least one occasion on which Kövesi left 160,000 forints for seven famous paintings. The average salary at the time was 2,000 a month.

Today Kövesi’s collection is exceedingly valuable. A couple of recent auction prices for paintings by artists represented in the collection give a sense of the value of the collection. A János Vaszary piece was sold in 2011 for 35 million forints. A Róbert Berényi painting was auctioned off for the same amount. Even the least expensive paintings in the collection are worth a few million.

Among the artists represented in the Kövesi collection are János Vaszary (1867-1938), Imre Ámos (1907-1944), József Rippl-Rónai (1861-1927), Vilmos Aba-Novák (1894-1941), Sándor Bortnyik (1893-1976), Izsák Perlmutter (1866-1919), László Mednyánszky, Margit Anna, Lajos Kassák, Jenő Barcsay, Béla Kádár (1877-1956), István Szőnyi (1894-1960), István Csók (1865-1961), Adolf Fényes (1867-1945), József Koszta (1861-1949), and István Pekáry (1905-1981).

As I said, before the change of regime no art work of any kind could leave the country because, the political leaders argued, the treasures of the nation must remain at home. The authorities included anything of presumed value in the list of forbidden items, not just Hungarian “treasures.” To pass through customs every questionable item needed a stamp from the authorities attesting to its “not worth keeping in the country–i.e., junk” status. As a result, these painters, some of whom may have acquired international fame, were unheard of outside of Hungary. It was a disservice to them and to the country.

One more thing about István Kövesi. He himself didn’t know anything about art before he decided to collect paintings. But he learned and also managed to find knowledgeable teachers among art historians and employees of BÁV. It was, however, always he who made the final choice. He obviously had good taste.

Source: Hungarian Spectrum

Like Hungarian Spectrum on Facebook

This opinion does not necessarily represent the views of this portal, your opinion is welcome too via info@xpatloop.com

LATEST NEWS IN current affairs