Xpat Opinion: Reverberations After Lajos Simicska’s Revelations About Viktor Orbán

- 11 Mar 2015 8:00 AM

The controversy began in 1991 when a dossier surfaced at the Military Security Office (Katonai Biztonsági Hivatal), which handled the leftover documents from the ministry of interior’s III/IV Military Counterintelligence Unit. At the time the Antall government asked János Kenedi, one of the top experts on the state security apparatus in Hungary, to investigate the contents of the folder. Kenedi came to the conclusion that Viktor Orbán had been a victim of intelligence gathering and was innocent of any wrongdoing.

There are others, however, who claim that there were documents indicating that the young Orbán wasn’t so innocent. Lukács Szabó, who was an MDF member of parliament between 1990 and 1994, claimed in 2002 that Prime Minister József Antall at one of the meetings of the parliamentary delegation indicated that the government had found “proof of wrongdoing in Orbán’s past.” Apparently, Antall repeated this statement to several MDF members of parliament. In addition, one of Antall’s undersecretaries in charge of the spy network confirmed the charge.

Then we have Péter Boross’s latest statement, which he gave to Pesti Srácok, described as a government financed internet site. Boross was an old friend of József Antall, who named him minister without portfolio in charge of the National Security Office and, a few months later, in December 1990, minister of the interior. Boross now claims that he “asked for all possible documents relating to Viktor Orbán, and from these documents it became clear that although he was approached by the officers of the ministry of interior he refused any cooperation with them.” Boross claims that he can prove Orbán’s innocence.

In 2005 an ad hoc parliamentary committee was formed to look into the financial affairs of the Orbán family. This was when Orbán bought a very expensive house in an elegant section of Buda, into which he poured an untold amount of money to make it suitable for the large family’s needs. About the same time he began building his weekend house in Felcsút. Orbán came well prepared, and I must say that I was somewhat taken aback by the incompetence of the co-chairmen of the committee. In any case Orbán, without being asked, released a number of documents relating to his alleged ties to the state security organizations.

For a while these documents were available on the orbanvictor.hu website under the heading “Valóság” (Reality). In 2012, when Ágnes Vadai inquired about his possible ties to the state security apparatus, he republished some but not all of the documents that had been available earlier. One of the documents not released in 2012 was titled “Suggestions for the creation of social connection” and contained personal information about Viktor Orbán.

According to the document, the “connection” began on October 20, 1981, shortly after Orbán began his military duties, and ended on August 20 when he “was discharged.” This would indicate that Lajos Simicska told the truth about Orbán’s reporting on his fellow soldiers during his time in the military.

Also in 2005 a retired colonel, Miklós Mózes, told Fejér Megyei Hírlap that “he had sat down a couple times for exploratory talks with [Orbán], but it soon became evident that he might be useful for several jobs but not for secret work with the state security organizations.” Mózes, however, said something else of interest. It happened that Orbán was called up for military service again a year after he finished law school.

Orbán apparently “by mistake” was sent to Tata instead of Zalaegerszeg where, as Mózes reported, the KGB was interested in the young lawyer and asked Mózes to facilitate his transfer to Zalaegerszeg. It is not impossible that by that time the Russians had become interested in the new young politicians who might have important positions after the demise of the Kádár regime.

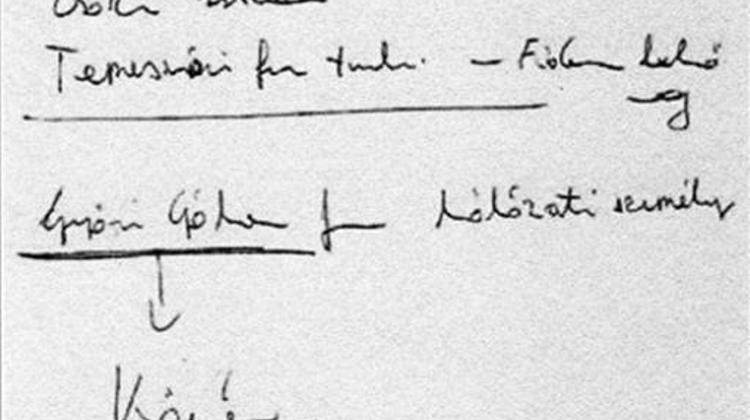

And now let’s move on to research conducted on informers by Csaba Ilkei, a historian whose sympathies lie with Jobbik. One of the documents that was not republished by Viktor Orbán in 2012 was a note in his own hand that is reproduced here.

István Csáki was a major in the ministry of interior’s III/IV unit. “Temesvári” was the pseudonym of an informer who, according to Ilkei, was Zsolt Szeszák, at the time a student at ELTE’s Faculty of Arts but here only identified as “Fidesz insider.” “Győri Gábor” was also an agent who was presumably, as indicated by the arrow, in some way connected to László Kövér. What Ilkei wanted to know was how Orbán could know Csáki or the pseudonym of Szeszák.

And there are other gaps in the story. László Varga, the historian of the state security network, did not find Viktor Orbán’s dossier named “Viktória.” It disappeared.

And finally, why doesn’t Viktor Orbán say outright that he never, ever reported on anyone in his life? Yesterday Orbán was asked by Hír24 about the “informer case” and he even answered, which is an exception to the rule. This is what he said: “The facts speak for themselves.

All information is available. I suggest that you study them. I find it sad that someone out of personal resentment would sink this low.” Magyar Narancs, commenting on this statement, noted that “although it is difficult to believe anything Lajos Simicska says, the question is lurking in the back of our minds: why can’t the prime minister’s office or the press secretary or he himself put together a simple sentence: “Viktor Orbán was not an informer and never reported on anyone.” Indeed, this is a legitimate question.

Source: Hungarian Spectrum

Like Hungarian Spectrum on Facebook

This opinion does not necessarily represent the views of this portal, your opinion is welcome too via info@xpatloop.com

Related articles:

Simicska: Orbán Said He Refused To Enroll As Spy But “Now I Don’t Know What To Think”

LATEST NEWS IN current affairs