An Englishwoman's Life in Communist Hungary: Chapter 2, Part 2.

- 1 Nov 2022 10:34 AM

Now You See It, Now You Don’t and House of Cards have been included as part of the Open Society Archive dedicated to this period in the CEU. You can read a serialisation of them here on Xpatloop. You can also buy the dual-volume book on Kindle as well as in Stanfords London.

Chapter two: Snow and Settling: Dózsa György út

Part 2 - Travel conundrums; shopping adventures

Following my walk from home to the station and the tube journey (which takes you under the Danube) I took the HÉV, a green, electric train which travels out to the suburbs. This goes directly to Óbuda and Lingua, and then on to Szentendre – a picturesque Serbian town on the Danube, home of artists, art galleries, and tourists.

As November wore on, our thoughts turned to our projected trip to West Germany to visit my aunt and her family. My mother and brother were to travel from England so that we would all meet at my aunt's for Christmas. By far the cheapest way for us to travel was by train through Czechoslovakia and East Germany, though this would entail obtaining visas.

Miklós advised us to book our seat-reservations early, so we went to the central travel office. On the ground floor were long queues waiting for hard currency – available only every three years, since Hungarians could obtain a passport only once every three years.

If they wanted to travel abroad more often they needed a letter of invitation from a friend or relative which guaranteed that the friend would meet all their expenses while they were in the foreign country.

On the first floor was the crowded büfé – a kind of snack bar where you could get anything from coffee and cake to alcohol and cigarettes, and on the second floor was the ticket office.

‘Just leave it to me,’ said Miklós.

We stood next to the glass window and waited until its beige curtains were whisked aside to reveal a seated woman, cigarette in hand, and then waited while she concluded a chat with a colleague.

‘Yes?’ she eventually asked.

‘We would like two tickets for the train to East Berlin on December 20th,’ Miklós said.

‘Before you can buy a ticket you have to have a seat reservation.’

‘Where can I get that?’ asked Miklós.

‘There,’ she said, pointing to the glass window immediately next door to her own.

‘Thank you.’

We moved over to the new window. After a few minutes the curtains opened to reveal the same woman.

‘Yes?’

‘Two seat reservations for the train to East Berlin for December 20th,’ Miklós repeated.

‘First or second class?’

‘First, no-smoking.’

‘That will be twenty-four forints.’

Miklós paid and she closed the curtains. We walked back to the first window.

‘Can I see your passport?’ she asked, as Miklós handed over the seat reservations. Miklós grimaced and gestured to me to show my passport.

‘You can't pay in forints if you're travelling on a Western passport.’

‘But this lady works here and earns here – look, here's her residence permit,’ Miklós replied.

‘Well, then you need a special permit from the National Bank.’

‘Thank you,’ said Miklós, taking my sleeve and pulling me away. ‘Don't worry, I'll try at Keleti station,’ he reassured me.

The following day he went back alone, where a young, less-experienced girl happily sold him the tickets. The total cost, with a first-class sleeping compartment return to Berlin was three thousand forints.

The following week I went to get our Czech visas. It was not difficult to get to the embassy and I soon found myself in a large, smoky room with many Arabs all filling in visa application forms.

The room was sparsely furnished with wooden chairs and tables; posters of Czechoslovakia, yellowing – whether from age or cigarette smoke I could not decide – graced the dingy wallpaper, and on the long wall opposite were two kitchen-like hatches, both closed.

I went to one where two people were already standing. After a few minutes the doors opened but when my turn came I found that the woman spoke neither English nor German, only Czech and Hungarian. This was not a great deal of help, nor very logical, since neither Hungarians nor Czechs needed visas.

I sat down to fill in the forms. Four identical forms had to be completed for each person, carbon paper was not available and a poster on the wall stated that carbon copies would not be accepted. In addition, only the first form had any other language apart from Czech on it, so in filling in the subsequent forms it was necessary to keep referring back to the first. Two photographs were needed for each person and as I had only one, I decided to leave the crowded, smoke-filled room and return another day.

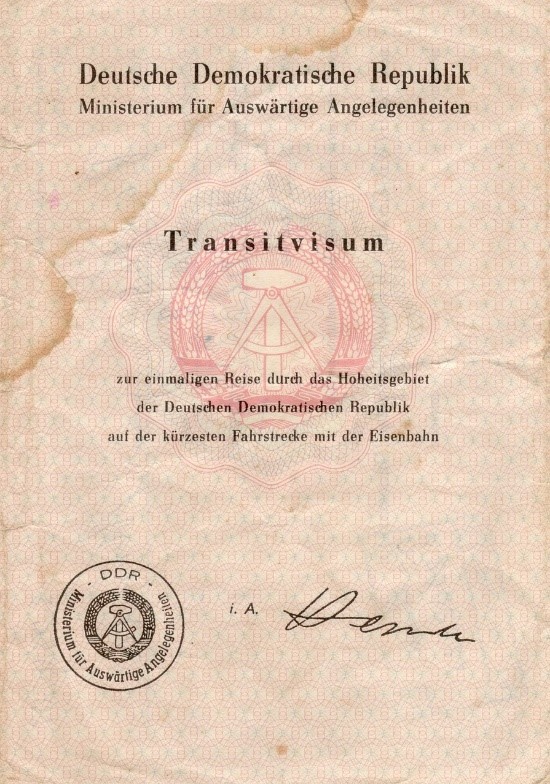

East German transit visa

I took the trolley bus home. The red trolley buses had been a gift, though many considered it a dubious one, from the Soviet Union to Hungary. The numbering on the trolleys begins at 70, Stalin's age when the gesture was made.

They seemed to be fitted only with a brake and accelerator, which might account for their erratic variations of speed, causing elderly women laden with shopping to lurch backwards at great velocity from one end of the bus to the other, taking other startled passengers with them every time the traffic lights changed to green.

The small interior was often stifling and smelly – in summer from sweaty, sticky armpits, in winter from mothballs and unwashed clothes. While the underground covered large distances quickly and the trams and buses shared the main road, the trolley bus (or the Geriatric Express as we dubbed it) alternately crawled and lurched along narrow backstreets.

1980s’ trolley bus Courtesy Fortepan/Magyar Rendőr

I managed to push my way to the door one stop before my usual one, having decided to pop into the small corner supermarket on my way home. In order to keep the heat in the shop, a thick, green felt curtain had been hung inside the door.

I fought my way through its heavy folds only to find there were no baskets. This necessitated two further forays through the curtain, first to the door to get a basket and then back, at the same time trying to avoid being knocked out by new customers coming through the doors.

Bread stood on a metal trolley, with a small piece of paper bearing the day of baking stuck into the dough of each one. It was 'today's' but when I prodded it, I realised it was already hard enough to have reached the category of an offensive weapon. Behind me, other fingers squeezed and prodded too.

Nearby lay a pile of tissue paper, barely large enough to cover half a loaf, for the purpose of wrapping the bread – a purely symbolic gesture to hygiene considering its handling by customers, the delivery man, shop staff and not forgetting the smears of sour milk in the plastic shopping baskets.

I joined the queue at the checkout. There was an argument going on regarding some bottles which a man insisted he had bought there, but which the cashier was equally determined not to accept. (Practically all glass jars and bottles had a deposit.)

‘This isn't one of ours, is it?’ called the woman to a girl behind the cheese counter.

She shrugged, ‘How should I know?’

‘Try the shop down the road,’ the cashier concluded, putting the empty bottles with the man's shopping and starting to deal with the next customer's basket.

The man continued to argue but was studiously ignored. Finally came the turn of the middle-aged woman in front of me. She wore the characteristic black leather coat, but set off against this was a pair of white training shoes with fluorescent green laces. She put her basket on the shelf next to the till, and the cashier began to ring up the prices, transferring the items to an empty basket.

Then, quite without warning, as she put her hand on a litre bag of milk, it burst, squirting both herself and everyone and everything within a radius of a foot or two. She sighed and called, ‘Ágnes, bring the bucket, will you?’ whereupon a girl appeared from behind another curtain, bucket and cloth in hand.

The queue waited while the cashier slowly and deliberately wiped her blue nylon overall, the till, the shelf and the floor, before handing the milk-soaked cloth to the customer to wipe her purchases in the basket.

A typical supermarket Courtesy Fortepan/ Magyar Rendőr

Having fought my way back out through the green curtain, I headed for home. The black cobbles of Dózsa György út shone as the subdued light of the lamps was reflected from the first, melting flakes of snow.

As I walked into the entrance I had a quick look in our letterbox, one of many, rusty, metal boxes whose keys did not fit, took out a letter and a folded piece of paper and made my way across the courtyard and up the steps.

Once inside the flat I saw that the letter was from Masped. I did not open it, I would not be able to read it. The other was a note from Éva saying she would call to see us at the weekend.

Of course, the rent. I walked over to the wardrobe and felt under a pile of sweaters where we kept the envelope containing our money. Current bank accounts with a cheque-book were something unheard of, and practically all transactions, from buying a car to buying a flat were conducted in cash.

On one of our summer visits Paul had gone by train with János to a small town in the country to buy a hi-fi. János took some thirty thousand forints in a paper bag which he clutched to himself throughout the journey. Our pay went into the envelope in the wardrobe and if it did not stretch till the second of the following month, state pay-day, we borrowed from friends.

This was common practice and not at all something to cause embarrassment, but on this occasion, it was alright, we had enough.

Paul arrived home a little after me, snow melting on his coat. I briefly described my trip to the Czech embassy and handed him the letter from Masped.

‘They want another two hundred forints from us,’ Paul said.

‘What! What for?’

‘I don't know, can't understand that bit.’

‘Well, they're not getting anything,’ I retorted. ‘First we pay in England, then we have to carry our own boxes and also pay for the privilege? And now they want more?’ ‘They ought to be paying us!’

Paul threw the letter in the bin.

We started to cook a simple dish: paprikás krumpli (paprika potatoes) which we had been taught to make by a woman who worked in the Liszt Society office in the Music Academy. She had invited us to supper and we had cooked it together.

A Hungarian meal without paprika is practically inconceivable: even the scrambled egg breakfast I had had on the train had been cooked with it and every cruet set has salt, pepper and paprika. In England it is a rather innocuous powder but in Hungary there are many varieties, from the sweet csemege to the lethally hot erös .

But the main surprise for us was that paprika is a vegetable, the September fields bright yellow and red with it. It is often compared to the more familiar red and green peppers, but actually bears little resemblance to them.

The yellow, sweet, paprika is richer in Vitamin C than an orange, and won a Nobel prize for the man who discovered this fact. It is commonly eaten raw for summer breakfasts with huge, sweet tomatoes and bread.

The hot, red variety is hung in weighty clusters to dry and ripen around the doorways and windows of peasant houses, especially in the town of Kalocsa. This one does resemble the chilli. Another hot variety is the cherry paprika, round and red. Paul had once made the mistake of supposing it to be a small tomato in his soup, had eaten it whole and practically exploded on the spot.

Gulyás soup Courtesy Wikimedia

Another useful source of recipes was Paul's students. He had asked one of his English groups to write out their recipes for a favourite dish. One boy in the group, a violinist called Tamás, began with an introduction explaining that as one of eight children, and son of a busy doctor, he would often cook at home.

He gave us his recipe for gulyás (goulash). For practically all visitors to Hungary it comes as somewhat of a surprise to find that gulyás is a soup. It is actually named after the gulyás (cowherds) who cooked their meals in an iron pot over an open fire on the great plains (the puszta) in the East of Hungary.

The thick stew-like meat dish we associate with the word 'goulash' is in fact what is cooked in Austria and Germany; Hungarian gulyásleves is a hot and spicy soup cooked with beef and potatoes and paprika and usually eaten with hunks of fresh bread.

Paul and Tamás would often discuss cooking before the lesson started, causing one of the numerous women who sit along the corridors of every floor of the academy (rather like attendants in a museum, though here no-one seems to be quite sure what their function is) to shoo them away complaining of hunger.

LATEST NEWS IN community & culture