An Englishwoman's Life in Communist Hungary: Chapter 2, Part 3.

- 9 Nov 2022 8:16 AM

Now You See It, Now You Don’t and House of Cards have been included as part of the Open Society Archive dedicated to this period in the CEU. You can read a serialisation of them here on Xpatloop. You can also buy the dual-volume book on Kindle as well as in Stanfords London.

Chapter two: Snow and Settling: Dózsa György út

Part 3 - Dentists and communication problems

As we finished eating, I felt a twinge in a tooth. I knew it was bound to happen sooner or later because I had had an abscess drained and temporary filling in July before we had left England.

‘What shall I do?’ I asked Paul.

‘Why don't we ask the neighbours? There's bound to be a dentist around here.’

The following morning we knocked on the neighbours' door. They were very quiet people, up to now we had only passed the time of day on the stairs, but we had been told by Éva that the woman spoke English and German. There was no-one at home.

Snow covered the plants in the courtyard and lay in dirty, melting pools on the old mats in the entrance to the building. Outside it had been shovelled to the side of the pavement and formed a white wall between pedestrians and the traffic.

The caretaker of every building is responsible for sweeping the pavement in front of it, while veritable armies of the most downtrodden looking men and women can be seen at midnight in minus twenty degrees, chipping away with their spades at the ice on paths and roads.

The snow brightened the grey and black facades of the smog-coated buildings. The pollution in Budapest often reaches intolerable levels, with two-stroke cars and buses belching out clouds of black smoke. Clothes, hair, curtains, everything becomes filthy in no time, the once-beautiful stonework blotted out by grime.

Many Hungarians I met had the image of London, not to say of England, as being permanently shrouded in a smoggy haze and were frankly sceptical and offended when I suggested that Budapest was far more polluted than any city I had yet visited. We noticed it particularly when we returned from the country, it was often suffocating.

I had intended taking the trolley bus to the Czechoslovak embassy again, but changed my mind when I saw that one had broken down on the corner. The driver had got out and was trying to pull down the two long arms attached to the electric wires above. One came down without difficulty, the other would not, which meant that the next trolley to come along would be unable to get past.

Instead, I took a tram and soon found myself once again in front of the two hatches in the wall of the visa department. This time both were closed with a few people waiting at each. I waited too. Then, as one of the pairs of doors opened, those at the hatch at the far end of the room ran to join the other queue. I stood at the end and waited for my turn.

The woman dealt with four or five people and then shut the doors. Those of us who remained waited again, when suddenly the far doors opened, sending us scuttling back to the other hatch. After one more such stampede, I was able to hand in my papers and flee the building.

I had an evening lesson at Lingua with a favourite group of students. They were all studying at the Foreign Trade College but also had jobs, mainly with foreign trade companies. They were a very humorous, enthusiastic and interesting group – one of them, Anthony, had not long retired from the Hungarian national ice-hockey team and his hobby was poetry.

Following our lesson, including the customary tea break, we piled into the cars of whoever had one and headed back into town. We had decided at the end of the lesson that the following week we would have a party.

I called in on Miklós on my way home. Sitting at the table was Endre, who was interested in working at Lingua. Endre stood up as I walked towards him.

‘Hi, I'm Endre – Andrew,’ he said.

His pronunciation was impeccable, quite the best I had yet heard from any Hungarian. He was strong, heavily built, and talked at break-neck speed in both Hungarian and English.

‘Where did you learn English?’ I asked.

‘In Warsaw,’ he replied, ‘Polish is my first foreign language, though.’

I could say nothing. He began to gather up his newspapers, the Herald Tribune and Time magazine off the table, swallowed the last mouthful of cognac and pulled on his fur hat.

‘I hope we'll meet again,’ he said to me, ‘Miklós tells me you're living on Dózsa György út. That's not far from us; I'll drop in some time,’ and flashing me a huge grin he slapped Miklós on the back and walked out of the door.

‘What do you think, should we employ him?’ Miklós asked me.

‘Well, I don't know what kind of a teacher he is, but his English is incredible.’

Miklós considered.

‘He's in a mess. He and his wife Kati decided to leave Hungary this summer, and overstayed their thirty-day visa in West Germany by a month. Kati wrote a letter to the headmaster of the school where she was teaching Russian, telling him all her negative feelings about Hungary, and later decided that she wanted to come back after all. Now, of course, their passports have been impounded and they're in trouble with the police.’

I arrived home to find Paul cooking and with the news that he had spoken to our neighbour about my toothache.

‘He's a surgeon at a hospital in a road called Baross utca,’ Paul told me. ‘He said that if we go there tomorrow morning at nine o'clock he'll meet us and take us to the dentistry department.’

‘I'll have to ring Miklós about my seven-thirty lesson and see if he or János can do it,’ I said, pulling my boots back on and checking that I had some two-forint coins.

I stomped over the snow to the two telephone boxes on the corner. I picked up the receiver in the first one; it was totally dead. The second one gave me a line, but try as I might, I could not get the money into the slot.

Banging the door behind me, I walked down the road to Keleti station. The only other phone box en route to the station allowed me to dial and insert my money, but when the receiver was picked up at the other end, my money was swallowed and I was left with the dialling tone, my money gone.

Muttering expletives, I made for the 24-hour post office in the station courtyard. Shouting emanated from a couple of the phone boxes inside the entrance of the Post Office, their occupants struggling to overcome the technical deficiencies of the instruments.

It no longer puzzled me that most things were organised by going personally to see people – it was quite literally quicker and considerably less wearing on the nerves than trying to make a phone call.

Public telephone Courtesy Fortepan/ József Reményi

Three boxes stood vacant – not surprisingly. Two were totally dead whilst in the third although you could hear the voice of whoever you were phoning, they were oblivious of even your most frantic shouts. I stood outside one of the occupied booths and waited.

I looked at my watch, half an hour since I had left home. I could have gone to Rákóczi tér in that time. I shivered. Eventually I got through. Miklós agreed to take my lesson, and when I put the receiver back, my two forints dropped back down to me. Just like a fruit machine: you lose some, you win some, but generally you lose.

A group of snow-workers dressed in fluorescent, orange jackets were smoking to keep warm, their spades leaning against a closed flower booth. Their warm breath formed clouds which hung in the stinging cold of the night air. I stamped up the road to get some feeling back into my numbed feet, wondering what these poor people could possibly earn and what desperate circumstances had necessitated their having to undertake such work.

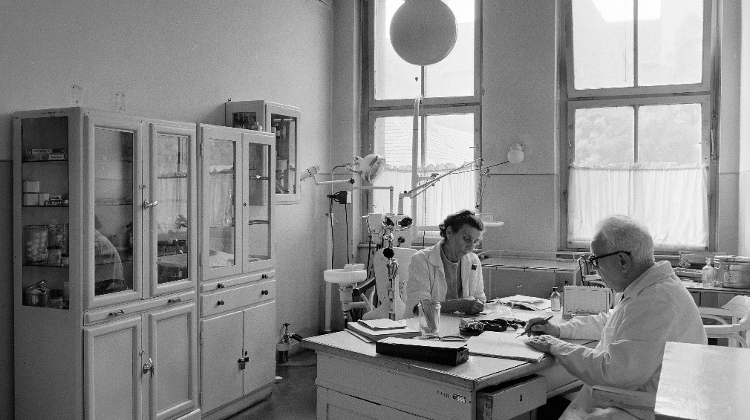

The following morning we looked up a few words concerning teeth and dentistry in the dictionary and went to the hospital. It was a large, red brick building, and at a few minutes past nine our neighbour came down the staircase. He shook us both by the hand and walked off down a corridor, beckoning to us to follow.

There was a long queue of people standing the length of the corridor, looking utterly bored. It was only as we were ushered into a room at the far end that I realised they were all waiting to see this same dentist. Our doctor neighbour said a few words to the dentist, whereupon I was directed to the dentist's chair and Paul took a seat by the window.

I saw with relief that the equipment was modern and new, and in fact exactly the same make as my English dentist had. It took only a painless moment to lance the gum and prescribe me some antibiotics. He said the tooth would probably have to come out sooner or later but it could wait.

Thanking him, Paul tried to press some money into his hand, we had been told this was expected for private treatment, but he categorically refused and smilingly opened the door back into the corridor. Sheepishly we walked past the row of people but observed not the slightest reaction, this kind of queue-jumping by friends of staff was obviously not uncommon.

At the dentist’s Courtesy Fortepan/ FŐFOTÓ

November 7th, the anniversary of the Russian revolution, was a national holiday, but an uneventful one. When I asked my students how it was celebrated, they merely replied that more people than usual got drunk that day. Nevertheless, it was remarkable to us how the authorities changed the days of the week to give several free days in succession.

November 7th fell on a Thursday, which would have been a national holiday. However, it was decided to make Friday a day off work, making a three-day weekend. Saturday's half-day would be worked on Thursday instead. Usually, such changes were announced through the media and were generally adhered to. However, it did happen that individual companies decided to vary these changes causing particular confusion for self-employed people who could find themselves expected to be in two places on the same day.

By the end of November, we had all the necessary visas and tickets to travel to West Germany for Christmas and a reserved sleeper on the train. The East German embassy, though forbidding and unfriendly, was quick and efficient, and the visas cost a fraction of the Czechoslovak ones.

The time leading up to our departure was filled with looking for Christmas presents, perusing the countless covered stalls that had sprung up to line the streets and fill the squares, selling anything from candles and jewellery to Matchbox cars and tubes of Smarties, along with gaudy Christmas decorations. In one of the subways I passed a cluster of bystanders watching a game which is played here and there around the city.

Three upturned matchboxes are placed on a cardboard box, one with a small red marble beneath it. The boxes are then slid about at lightning speed while the gamester calls, ‘Here's the marble, where's the marble?’ occasionally lifting one of the matchboxes to reveal the red marble beneath.

At double or quits you could bet five hundred forints on the box you thought concealed the marble when they finally came to rest. Obviously, some sleight of hand guaranteed you never chose the right one. I walked on, thinking how very many aspects of Hungarian life in general were epitomised in this game: an exciting swirl of activity, nothing where you thought it was, and a feeling of bewilderment at the end of it all.

Illegal gambling game played around Budapest’s streets

Main photo: November 7 Square (Oktogon) Winter 1984 Courtesy Fortepan/ Anna Krizsanóczi

LATEST NEWS IN community & culture