'An Englishwoman's Life in Communist Hungary': Chapter 4, Part 5.

- 12 Apr 2023 9:16 AM

Now You See It, Now You Don’t and House of Cards have been included as part of the Open Society Archive dedicated to this period in the CEU. You can read a serialisation of them here on Xpatloop. You can also buy the dual-volume book on Kindle as well as in Stanfords London.

Chapter four: Courtyard and Characters

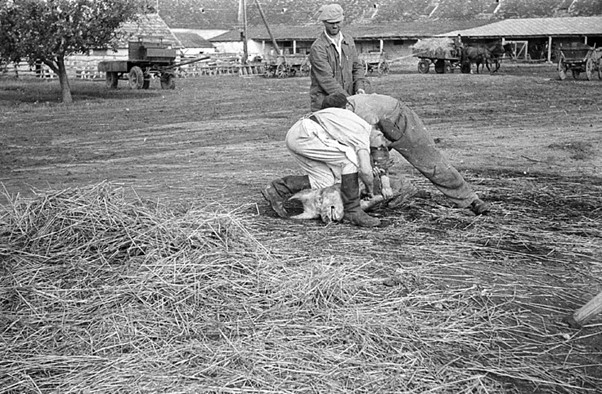

Part 5 – A pig killing, and an unwelcome invitation

I remained in Mezőhegyes for a week, soon becoming accustomed to being whispered about by passing school-children, (‘That's the English lady!’) as we passed one another in the small park that lay on my way to where our lessons were held.

My evenings were invariably spent with Laci and Alice and sometimes other members of the group would join us. On the Saturday which marked my departure there was to be a pig killing - traditional in the weeks before Christmas - at a friend of Laci's. As the vet, he had offered to commit the terrible deed - the pig was usually bled to death.

I arrived at Laci's later in the morning to find Alice washing the pig's intestines in the sink ready for filling with minced meat for sausages. The kitchen floor was covered with deep trays of meat to which was added paprika, salt, pepper, garlic and blood.

The mixture was then stuffed into the intestines, and a winter store of food was made. My only contribution was to peel and press the garlic, but I later considered it a generous one in view of the fact that my hands smelt for days afterwards.

Back in Budapest and at Lingua, new groups had been started. One of mine contained a man who proudly told me that he worked for the Hungarian Meat Trust. He asked me once, confident of an affirmative reply, whether Hungarian meat wasn't of the very best quality. I assured him that it was, but added that I missed eating lamb and had so far failed to find it at any butcher's shop.

‘But you can get it anywhere!’ he protested.

‘Where?’

‘All over the place!’ he repeated.

I decided not to press him further.

Some nights later I was teaching my favourite group of students - including Geoff, all of whom were reaching the end of their school days and preparing for university entrance. There was a knock at the door, and when I opened it I saw my man from the Meat Trust standing in the corridor.

‘Hello,’ I said. ‘Your group is tomorrow, Wednesday, not tonight.’

‘Sorry to disturb you,’ he said, ‘I've just brought you this,’ he continued holding a large, white carrier bag out towards me. I took it from him, surprised at its weight.

‘What is it?’ I asked.

‘Half a lamb,’ he replied, ‘Five kilos. I hope you like it,’ he added, as he saw the dumbfounded look on my face. I had rudely forgotten to thank him in my sheer amazement, and the perplexity of calculating how I would fit five kilos of lamb into a freezer the size of a shoebox.

‘Thank you,’ I stammered, ‘thank you very much.’ He smiled and turned towards the lift, as I walked back into the classroom clutching the bag. ‘But what shall I do with it all?’ I asked my laughing students. But then I had an idea.

One of the group was a Piarist novice monk who lived in the town in a Catholic school which housed other monks. ‘You take half of it,’ I told him. ‘Get them to cook it for you, I can't possibly use all this meat.’ I cooked my half and invited Geoff, who had never eaten roast lamb before, though we had to make do without the mint sauce.

Christmas came and went with our customary journey to Germany. Mrs. Varga came out to greet us when we returned. As we exchanged pleasantries, I noticed that the Molnár's flat next door to her not only had its curtains drawn, but a large padlock on the front door and some sort of official-looking notice stuck above it. ‘What's that?' I asked, nodding in the direction of her neighbours. She paused.

‘They died over Christmas,’ she said.

‘What? Both of them?’ I asked in amazement.

‘Yes. Their chimney hadn't been cleaned and all the poisonous gases from the tiled stove came back into the room. Their daughter found them on Christmas day. He was sitting in the chair, a book on his lap, and she still had her knitting beside her. The council came and locked the place up. Terrible.’ She was obviously upset, so we just nodded silently and let ourselves in the front door. When I met Miklós some days later I found his aunt and uncle had both also died in identical circumstances.

Chimneysweep Courtesy Fortepan/ Sándor Bojár

Just one year previously Laurence had been staying in our flat. Since then, he had moved to a flat near Orczy tér, a market square with a similar reputation to Garay tér. He was now installed on the thirteenth floor of a fifteen-floor block, and we paid him a visit as soon as he returned from Christmas in England. Laurence was by now teaching composition at the Music Academy and was also involved in teaching students at the College of Theatre and Film.

It was snowing as we left our building in Szinyei utca to walk to the 33 bus stop. As we made our way up the street, we suddenly saw a notice on a metal stand, right in the middle of the path saying: DANGER! We looked around. No road works, gas works, holes in the pavement, in short, nothing dangerous at all that we could see. We walked on, still puzzled.

When we reached Laurence's flat, we were surprised to see him arrive at the door wearing only a pair of swimming trunks, and with his balcony door wide open. However, as we walked in the heat hit us, it must have been twenty-eight degrees.

The centralised heating system which supplies most housing estates of this kind was notorious for the variability of heat supplied to different buildings, according to their distance from the heating plant. Added to the fact that Laurence was presumably close to the source of power, his proximity to the top of the building was turning his flat into an inferno.

Laurence’s street – Courtesy Fortepan/ Sándor Bojár

He had brought a good supply of mince pies and Christmas puddings with him from England which we readily devoured in the tropical temperatures, exchanging stories of our Christmas travels, and his plans for forthcoming compositions. We had been seeing each other regularly since we had first met, often cheering one another up with the aid of our shared English and rather flippant sense of humour - often the only antidote to the illogical and absurd difficulties of everyday life.

Laurence had already been able to speak Hungarian when he arrived, having learnt it from his grandmother, who had also left for England in 1956 but had never learnt English. However, Laurence's new-found Hungarian friends were apt to fall about in fits of laughter when he came out with expressions or slang which his grandmother had presumably picked up in the twenties and thirties. But his prowess soon developed and we envied the ease with which he slipped from one language to the other.

On the whole, we had all managed to steer clear of a certain type of Hungarian who liked to associate with foreigners, sometimes in order to procure goods unavailable in Hungary, or to be invited abroad on holiday, but sometimes just to have a kind of status symbol in tow.

It was under such circumstances that the three of us were invited to a party of well-to-do, self-employed people, the Hungarian equivalent of yuppies. We were very reluctant, trying every possible excuse we could come up with, but to no avail. Laurence's acquaintances had obviously ear-marked us all as the star attraction for their guests and were not to be put off.

Laurence was particularly irritated since he felt certain they knew all our excuses were just that, and still they chose to force us to accept the invitation in the knowledge that we did not want to go.

A few days before the party we came up with an idea: we would go, but pretend we had a recording job at the radio from ten o’clock - recordings were often done at night - and so we could leave at nine-thirty, hopefully having had some food but thus escaping the boring ‘interview’ stage to which we would inevitably be subjected later.

Laurence came to our flat first and we made our way together to the dreaded event. Walking along Szinyei utca Laurence stopped at the sight of the DANGER! notice which was still there, but which we now passed daily without a second thought.

‘No, we don't know what it's here for either,’ I said, anticipating his comment. He looked around, then up. We followed his gaze. Up above us on the second floor of the building was a balcony, hanging precariously at an angle of some thirty degrees from the main structure. There was not even cordon to keep anyone from walking, at their peril, immediately beneath the hanging ton of cement and plaster.

Collapsing balconies Courtesy Fortepan/ Benjamin Makovecz

When we arrived at the party a few elegantly dressed men and women were already sitting talking. We were introduced to everyone and sat in the middle of the sofa. We felt totally out of place, at least I had a dress on, but Laurence in jeans and t-shirt looked as if he were trying to make a point. As there was no sign of food yet, we accepted drinks and began to answer the barrage of questions.

‘But do you mean you really like living here?’ one woman asked.

‘Where exactly do you live in Budapest?’ asked another.

Laurence's mention of Orczy tér was greeted with an embarrassed smile and followed by silence. I looked at the beautiful, antique clock on the wall. Only eight o'clock.

‘Did you go away for Christmas?’ a man asked, seeming unconcerned which one of us should answer.

‘Yes, we travelled to Germany,’ I replied.

‘And I was at home in Wales,’ said Laurence.

‘Do you ski?’ continued the man looking at Paul.

‘I'm afraid not,’ he replied. Yes, that was what had struck me about all the people here, I thought. They were all suntanned in February; presumably they had all been skiing, or to a solarium.

The inevitable questions about work and the like continued, while we stole impatient glances in the direction of the kitchen to see if any food would be forthcoming. We had already explained our sad intention of leaving the party at nine-thirty to our hosts the previous week, and now we mentioned it to the other guests.

‘Oh dear, what a pity,’ said the woman in a short, pink dress with huge, black polka-dots on it.

‘But how long will the job take?’ asked someone else, ‘Surely you could come back afterwards?’

‘Oh, you can never tell,’ said Paul, ‘we just have to stay until it finishes.’

‘But we'll be partying till four or five,’ our host broke in, ‘you must come back when you've finished. Yes, I insist.’ There seemed to be no escape.

The time wore on slowly, the food arriving only about ten minutes before we had to leave. Trying to look suitably fed up and bored by the idea of working on a Saturday night, we bade our farewells to everyone and walked out onto the cold, dark street.

‘Now, what?’ I asked.

‘Let's go to your place,’ said Laurence, ‘Have you got any food at home? I'm starving!’

‘But what shall we do about going back?’ asked Paul, ‘I'm not going back.’

‘I know,’ said Laurence, ‘we'll ring them up later, pretend we're in the studio, and say everything's gone wrong - you know, faulty equipment, lost script, usual kind of thing, and that we'll be there for hours.’ We agreed on his plan.

Back in our flat we had some food and wine, wondering when would be a good time to telephone. Unfortunately, not having a phone meant we would have to scour the streets for a payphone that worked. Sometime around one o'clock we began our search. Luckily, the nearest phone to our flat was working. Laurence volunteered to make the call in Hungarian.

‘Yes, it's Laurence here, I'm ringing you from the radio. No, we haven't finished - the sound engineers arrived late, one of the microphones isn't working and now we find a page of the script hasn't been translated so I'll have to do it... Yes, typical, isn't it? We're really fed up with it.’

Paul and I tried hard to smother our laughter at Laurence's award-winning performance. But then, quite without warning, an ambulance rounded the corner, its siren screeching. Now the game would be up, surely.

‘What's that?’ shouted Laurence into the receiver, ‘yes, not even the telephone in the studio works, so we had to come out onto the street to make this call while the engineers are trying to sort out the mike,’ he quickly ad-libbed. When he put the receiver down we all squeezed back out of the phone box and laughingly accompanied Laurence to the bus stop.

A telephone kiosk Courtesy Fortepan/ Benjamin Makovecz

Click here for earlier extracts

Main photo: Pig killing - Courtesy Wikimedia

LATEST NEWS IN community & culture