Surprising Expats: Hope Reese, New York Times Journalist, Author, Editor

- 8 Jul 2025 10:45 AM

If you would like to be interviewed as a Surprising Expat, please write with a few details of what you do, to: Marion by clicking here.

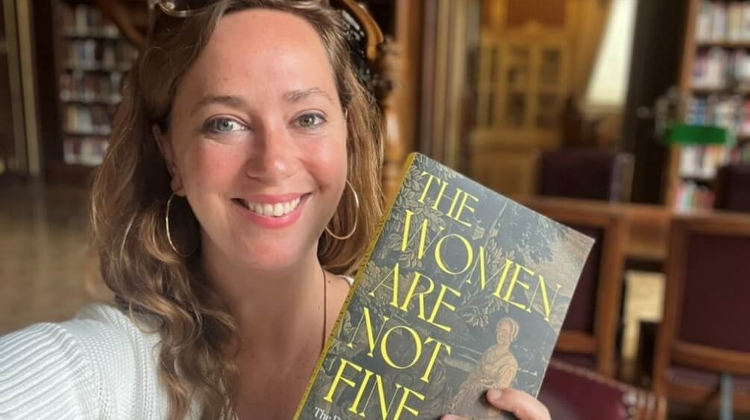

Hope Reese welcomes me into her apartment in district XIII – books crowd every available surface, among them her forthcoming volume to be published on July 1 : The Women Are Not Fine: The Dark History of a Poisonous Sisterhood, with Brazen Books (a Hachette UK imprint).

It is seven years since Hope settled in Budapest – though she is somewhat reluctant to describe ‘settled’ as her status, in spite of now having permanent residency. Throughout her 20s and 30s Hope lived in many places – from Copenhagen to Kentucky, and is used to keeping her options open.

Born and raised on Long Island, New York, Hope earned her Master’s in Journalism at Harvard University and moved to Louisville, Kentucky, to start work as a freelance journalist. Years later, she felt the pull to move abroad.

Hope had visited Prague in 2009, which was she said was life-changing. "It gave me a taste of not just the architecture, but the mood. I like this dark mood – there's something romantic to me about it. The cafés, the beauty of the place, all felt different."

In April 2018, Hope began a six-week sojourn in Budapest. She knew nothing about the city and had no plans beyond going to the baths. On the advice of an Irish friend to just ‘feel’ the city and wander around, Hope did just that. “I loved it. I was just stumbling around ... I didn't even know it when I ended up at Parliament. When you're on an itinerary, sometimes you miss the magic of exploring and discovering.” And the more she stayed, the more she liked it.

In terms of adapting to a culture very different from that of her native United States, Hope has acquired sufficient fluency in Hungarian to get by, and has explored many parts of the country – her favourite city being Pécs. Moreover, some aspects of life that initially proved frustrating, such as the slow pace of life, have become a source of pleasure: “I didn't like it in the beginning so much, but I just feel there's a lot of freedom, a lot of quiet. There's just a kind of calmness in the city that I love.”

Hope has also seen another aspect to an oft-mentioned bugbear of newcomers: “The frustrating thing wasn't so much the language, but the attitude of a kind of unhelpfulness. And that’s very different from a customer-service-oriented American attitude. But there's two sides of that: you're actually not pressured here. You're allowed to stay somewhere forever and just be yourself. You're left alone. It’s kind of nice.”

It was at an Open Mic event – a part of what Hope describes as Budapest’s ‘very thriving creative community’ – that she happened to talk to a man whose grandmother had poisoned (but failed to kill) his grandfather, something that meant his father had grown up without his mother who spent twenty-five years in jail. “And he said, you know, so many women back then were poisoning their husbands,” she recalls.

This chance conversation triggered Hope’s imagination, and the result is her new book.

After speaking to her friend, Hope describes a string of coincidences first leading her to an RTL journalist who introduced her to a short news story about these events, to the discovery that the grandmother of one of her students came from the village of Nagyrév where such poisonings had made the village infamous.

“I went to Nagyrév with him and my interest was sparked. At that same time, I was approached by a literary agent who asked if I was working on anything interesting, did I have a book idea. I called her, and said: ‘Here's the idea.’ And that was it.”

As stated on the cover of Hope’s book, this is ‘The greatest mass poisoning of modern times.” It centres around an early 20th-century midwife – innocuously known as Aunty Zsuzsi (Susan) – in the isolated village of Nagyrév, who not only carried out illegal abortions, but supplied arsenic to village women bent on poisoning their husbands. She was not unique in doing this – other examples are recorded – but where Aunty Zsuzsi diverged from others was in making a thriving business of her pursuits.

“The first poisonings happened around 1911; the deaths we looked at were between 1911 and 1929, so it's nearly two decades, and obviously there are different people behind these murders,” Hope explains, as she produces a hand-drawn chart of the complex inter-connections between Aunty Zsuzsi, other local women and subsequent murder cases. “Many of the poison-distributors were midwives, and older women.”

A professor at CEU (Central European University) had a rare copy of an academic volume in English about the Nagyrév case, which he lent her. “As I was reading this, I thought, this is really an incredible story! Many people have said ‘why don't you write it as fiction?’ but it's just too interesting, and I'm a journalist, and I really want to stick to the truth. There's no reason to make up something here.”

Hope began work in earnest with the help of a PhD History student at CEU, consulting a Hungarian book on the topic followed by researching primary sources including court records, testimony from the 1929 trials, archival newspapers and police records.

“I think these isolated communities were a little bit cut off from the world. There's no police force there. There's no doctor there. Who determines the cause of death is the coroner,” she says. “In this case, the coroner was married to one of the poisoners! Everybody knew what was going on. It was not something that was hidden. It was something that was ignored or swept under the rug.”

Husbands were not the only victims of the poisonings. Mothers-in-law, fathers-in-law and badly injured war veterans were also ‘put to sleep’ by the women. There is clear evidence of domestic abuse in relation to many of the women who poisoned their menfolk. “Everybody was desensitized to violence there. Everything from killing infants to being injured in battle and witnessing horrible acts, to having to kill. It was a pretty brutal society,” says Hope.

In addition to writing the book, Hope has been a journalist for over a decade, writing regularly for The New York Times and dozens of other publications, primarily about matters pertaining to America, though she has interviewed Ernő Rubik and the psychologist Gabor Maté for articles. Asked about further book projects, she says, “Despite how stressful and miserable a lot of it has been, I somehow want to write another book.”

Meanwhile, Hope continues to enjoy her life in the 13th district, alongside her inseparable feline companion, Béla: its market, its proximity to the Margaret Island and her beloved Hajós Alfréd pool where she’s training in readiness for a renewed swim across Lake Balaton; she continues to detest fruit soup and love töltött káposzta (stuffed cabbage) along with Hungarian ‘homey’ food in general. And she loves to walk around the Palótanegyed (palace area) of Budapest’s 8th district where she first stayed upon her arrival.

“I feel grateful that I can make the choice to live here. I know not everybody can. It's a big privilege to be able to just come to a country, be accepted, and be welcomed. It continues to feel pretty magical.”

Links:

Hope’s website gives news updates and events, or you can follow her on Instagram.

Her book will be available in Kindle format and as an audiobook, and is planned to be translated into Hungarian, Japanese and Russian. Pre-orders signal interest to bookshops and are important to first-time authors. You can order yours here, or buy it at Bestsellers, Massolit and other local bookshops.

Marion Merrick is author of Now You See It, Now You Don’t and House of Cards and the website Budapest Retro.

If you would like to be interviewed as a Surprising Expat, please write with a few details of what you do, to: Marion by clicking here.